I sometimes wonder what the lawyers who clear samples for American recording artists would make of Jamaican dancehall albums from the 70s. Biz Markie and De La Soul both got in big trouble for samples that were less than three seconds long; the average 70s dancehall song has the artist chatting over a borrowed instrumental riddim borrowed wholesale from another recording. The most popular riddims were repurposed so often that there are hundreds of compilations featuring ten or twelve artists chatting or singing over the same instrumental track.

In some ways early hip-hop did much the same thing, with artists rapping over James Brown or Chic instrumentals. Still, its not like there are scores of albums with MCs rapping over “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg,” or “Sexual Healing,” which is roughly equivalent to what Jamaican dancehall albums are. For the most part, the albums were released by the same studios that had the rights to the instrumentals, but I don’t think that the Jamaican copyright industry in the 70s was nearly as robust as the Americans was. Not that that’s a bad thing.

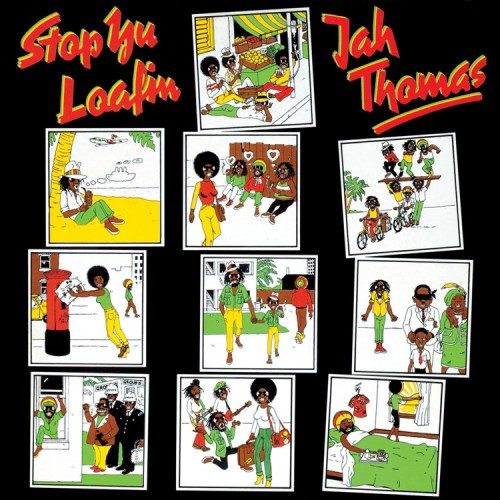

Greensleeves has just reissued Nkruma “Jah” Thomas’s 1978 album “Stop Yu Loafin,” which is a prime example of 70s dancehall. The album sees Jah Thomas chatting over ten instrumentals from the Channel One studios. There are instrumental versions of songs by John Holt and Horace Andy that were hits earlier in the decade (Horace Andy’s “Skylarking” provides the riddim for the title track). There’s also a instrumental of a cover of Bob Marley’s “Waiting in Vain”, which means that it is a version of a version. The riddims are backed by the powerhouse team of Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare, whose drums and bass form the backbone of many reggae songs from the 70s through the present. They were Jamaica’s answer to Motown’s Funk Brothers.

Lyrically, “Stop Yu Loafin” is in the vein of Big Youth or Trinity, or Jah Lyon or Jah Stitch for that matter. Thomas chats rhythmically and melodically over the beat in a casual, unhurried style. It’s almost as if he is coming with the lines as he’s saying them, and it is his delivery as much as his lyrics that make the songs. Which isn’t to say he isn’t saying anything. His lyrics are full of references to Black Pride, Pan-Africanism, and Rastafarianism. He even has a song to his namesake Kwame Nkruma, the first Prime Minister of Ghana. The rhymes tend to be simple and playful (“Mr. Nkruma him check out the rumor/Natty dread him sleep on the bed”). If you are looking for stellar lyricism or deep poetry, you’ll be disappointed, but Thomas still manages to get his message across.

At the time of this album’s release 35 years ago, chatting over albums was new and these tracks sounded much more novel and exciting to the Jamaicans who were listening to them over booming sound systems. After three and a half decades of dancehall and hip-hop, Jah Thomas sounds quaint. That simplicity and quaintness is the charm of this album. Thomas rides the groove of each song, and they throb along with Shakespeare’s bass and Thomas’s mellow timbre. “Stop Yu Loafin” may not have the flash and bells and whistles of contemporary dancehall or rap music, but it also doesn’t have any of the BS or posturing. This is dancehall, pure and simple, and a great example of how good early deejay music could be.