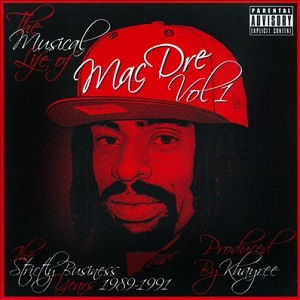

Andre Hicks’ posthumous releases might just outnumber Tupac Shakur’s. The collection at hand deserves a closer look because it operates with a sense of history, gathering tracks from the earliest stage of his career. Although Mac Dre’s years with producer Khayree normally fly under the banner Young Black Brotha (also the title of his very first EP from 1989), the label was called Strictly Business at that time. As for the exact duration of these ‘Strictly Business Years’, there’s some doubt that the collection’s 13 tracks all have their origin in the timeframe given in the subtitle since some of them weren’t released until 1992 or 1993, and even factoring in a prison term it’s unlikely that everything here falls into that three-year period.

What is confirmed is that it all started in 1989 with the 19-year old releasing the EP “Young Black Brotha” (not to be confused with “Young Black Brotha – The Album,” which concluded the Strictly Business era in 1993). Dre’s debut release is represented with three tracks – “Young Black Brotha,” “Livin a Mac’s Life” and “Too Hard For Da Fuckin Radio.” Spelled “Too Hard For the Fuckin Radio” here, the latter song is exemplary of Mac Dre’s music. Loved in and highly representative of the Bay Area but long ignored in the rest of the country, it embodies the independent spirit that drove a rap scene that didn’t constantly hope to be discovered by the national music industry. The irony is that Khayree was also part of one of the most successful rap albums of that time, Vanilla Ice’s “To the Extreme,” but that’s another story.

“Too Hard For the Fuckin Radio” doesn’t revel in the fact that it doesn’t conform to a radio format the way N.W.A or the Geto Boys would have done. It’s not something he rubs in the face of white America or the music industry but a self-evident fact. Showing traces of Schoolly D and Too $hort, Mac Dre’s performance is however rhetorically more refined, the playfulness elevating the raps to the level of what we know as ‘game’. Khayree wisely plays support with a back-to-the-basics, yet also slightly tongue-in-cheek beat whose kicking drums are themselves a significant reason the song was too hard for radio.

Perhaps San Francisco’s KMEL, an early supporter of rap music on the West Coast, was an exception along with college and community radio, but remember this was music that was mainly spread by word of mouth. It is also music that derived much of its identity from its home turf. Mac Dre wasn’t only out for personal gain and fame, he also came to represent the Crestside of Vallejo, setting off a tradition that over the years would cement this neighborhood’s reputation for rap especially grounded in its place of origin. At the same time it inherently had a broader appeal because just as the anger of Compton, California, echoed all over America, it too spoke for many others living under similar conditions. Most rappers in the earlier days of rap with a socially conscious/street edge were aware of the fact they were pieces of a bigger puzzle, that theirs was the story of many. “Young Black Brotha,” Mac Dre’s self-portrait of the artist as a hoodlum (to take up a turn of phrase coined by 3rd Bass) has a noticeable critical undertone:

“Young black brotha, can never be a lover

He keeps a joint in one hand and heem in the other

So fly, you never see him bummy

He’s never had a job but keeps a pocket full of money

Live low, Daytons and Vogues

A beeper on his belt and a gang of hoes

Been in and out of jail since the day he was ten

The hall, the county, and next is the pen

See he really doesn’t know what the game’s about

Get in, stack a bank and get the fuck out

Because a d-boy’s life is cool at first

But in the end it’s the pen or even worse a hearse

Young brotha loves to get keyed

Cause he feels so good when he’s hittin’ the weed

He’s never been to high school, let alone college

And has so much game and too much knowledge

Some call him a sad case, but how do they figure?

Many wanna be like that young nigga

And it’s not just him, it’s another and another

Cause many of us live the life of a young black brotha”

It’s that sense of reality that attracts many people to rap to this day. The Mamas & the Papas were famously “California Dreamin'” in 1965, but Mac Dre and Khayree (and guest Coolio Da’ Unda’ Dogg) were “California Livin’,” focusing not so much on the cliché image of California that already existed before the ’60s, but the frequently dangerous streets where the only thing glamorous are the customized cars, “where you can drop the drop, or blow the brains / hit the intersection and do some thangs,” but also where “brothers on the savage grind” are “livin’ way too real.” Obviously it also celebrates the party and player lifestyle that always had its place in West Coast rap, and it foreshadows the movement Mac Dre spearheaded much later in his career, hyphy. “California Livin'” (here included in the original 1991 version) may not be a universally understood ode to the most famous of all U.S. states but it’s a proud moment in Bay Area hip-hop history.

The spirit of history hovers over “The Musical Life of Mac Dre Vol. 1,” rising from song blueprints for the kind of rap music that isn’t purely action or fantasy but has some advice for you, sometimes matter-of-factly, sometimes condescending, sometimes sympathetic. In tracks like “Livin a Mac’s Life,” “Da Gift 2 Gab,” or “On My Toes” MD gives up game in truly exemplary fashion. Even across music that may sound dated to today’s ears, the era’s influence on two decades of rap (and counting) is heard crystal clear.

With rap opening up, becoming more honest and personal in recent years, revisiting these years can also serve as a reminder that straightforwardness has always been one of rap music’s strengths, even as it ever so often was cloaked by superficiality. On “They Don’t Understand” Mac Dre and partner Ray Luv rhyme with reason about their decision to choose the rap game over the crack game. Dre relates how he got caught up in the fast life, exercised writing and rapping in jail and, with the help of Khayree, learned to make a living as an artist. Likewise, “Times R Gettin Crazy” is driven by Dre’s hope that others don’t make the same mistakes:

“Children – from the black minority

Locked down in the Youth Authority

DeWitt Nelson, Washington Ridge

These are places they lock down kids

It ain’t right, it wasn’t meant to be

We don’t belong in no penitentiary

You got a talent? You better use it

Pick up a pen and write some music

And if not, boy, play sports

Get to hoop-ballin’, hit the courts

The dope game just ain’t cool

You better try and stay in school”

It’s a sad irony that the two songs that follow the above and close the collection (apart from an instrumental) feature vocals that were recorded on lock-down, “It Don’t Stop” and “Young Mac Dre” both being rapped over the phone from the Fresno and Sacramento county jails. The ultimate tragedy of course is that Andre Hicks’ remaining time on this Earth wasn’t only limited because he would spend a considerable part of it behind bars but by ending much too early in 2004.

Numerous have been the attempts to commemorate (and capitalize on) Mac Dre’s death. This isn’t Khayree Shaheed’s first time and at least one of the two tracks he claims to be ‘unreleased’ is not (factual liner notes would also have been preferred over the sentimental thank-yous), but he deserves credit for reissuing Dre’s earlier works in some context, unlike the excessive “The Best of Mac Dre” series. It makes for an essential listening for those interested in the artist and the place and the time reflected in his first recordings.