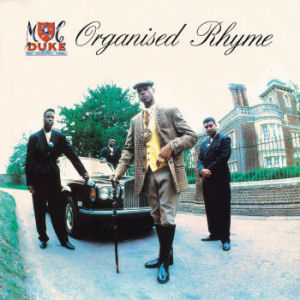

MC Duke’s “Organised Rhyme” could be the British equivalent of Maestro Fresh-Wes’ “Symphony in Effect.” Both album artworks try to implement a typical lofty ’80s rap name visually. The Maestro’s tuxedo suggested a conductor in the area of classical music, the Duke’s attire evoked landed gentry. But while Fresh-Wes established himself as the godfather of Canadian hip-hop with his 1989 debut, “Organised Rhyme,” from the same year, is merely one album among several that constituted the first wave of British hip-hop.

Like many of his peers in ’80s hip-hop, Anthony Hilaire was a dancer first, his footwork taking him onto national television and the stage show of pop act Modern Romance. Although part of the Covent Garden scene where he tested his rhyme skills at open mics, he almost accidentally stumbled upon a rap career, famously responding to the boasts of a newly crowned DMC MC tournament winner and taking him out in the process in 1987. Witnessig the event, UK hip-hop vanguard Derek B placed him at the budding Music of Life label, on whose compilation “Hard As Hell” Duke debuted with the track “Jus-Dis.”

His first steps in the studio were influenced by American originators, “Jus-Dis” bearing an uncanny resemblance to the works of T La Rock, while “I Don’t Care Anymore” mimicked Ice-T “Rhyme Pays” era. Once the album hit the shelves, the East London MC had not only moved away from US rhyme styles but from the accent as well. The overseas influence now mainly manifested itself in the rapper’s pro-black pose. Yet he made a clear effort to adapt it to local conditions, addressing both the burning issue of South African apartheid and the historical burden of European colonialism. Also, London had seen violent protests in Brixton the years before, so the 23-year-old certainly could translate American rap rage to his own situation and surroundings:

“Hey! I don’t say it’s right to fight

but I must incite a riot tonight

My plight is this: I was born on the black side

from my head right down to my backside

And my homeland is run by another

Gimme that back (Yo, word to the mother)

Land in my hand I have not felt

cause my race still reels from the deals you dealt

Knelt and prayed to a god you made

stolen from us in a different age

Bold as you are, livin’ like a star

while my mind still rocks from a mental scar

Nah, you don’t wanna know how it feels

I’ma blow up your ship and rip the keel

Here’s the big payback, line for line

The bum’s a prime – in Organised Rhyme”

The opening title track proceeds to attack with heavy drum machine backing, frantic cutting and sampled bits and pieces while Duke vents his frustration with the powers that be. It may not be the sharpest analysis, but he brings forth those simple but compelling couplets of late ’80s rap:

“To rock the joint and make my point clear:

There ain’t a race in the place that I fear

But I see other races are afraid of me

They call me a villain and Jamaican thief

Paranoid to the bone

And now old ladies are scared to leave home

Yeah, I used to do that, a stick-up kid

Of course – I learned from the things you did

But now I stand back and bust my rhyme

I did the crime and then the time

A model citizen, and I pay my taxes

while the government cools out, relaxes

on money, stolen years ago

I speak the truth and you fear the show

You want me to say, ‘Ooh, I’ll play the game’

(Hell no) I refuse to act tame

Shame, cause I caught you sleepin’

Big fat stomach while the kids are weepin’

That’s alright, cause we’ll get our time

The bum’s a prime – in Organised Rhyme”

Like the stateside records that influenced it, “Organised Rhyme” is an act of emancipation and empowerment – from the perspective of a British blackman, yet also aware of the bigger picture. He shortens the ’84 top ten single “Free Nelson Mandela” (sampled only for the intro, before a “Say it Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud” loop sets in) to simply “Free,” stressing the necessity for freedom for all oppressed people of color. The examples he gives concern mainly South Africa, but the conclusion he draws is “that one day the blackman will be free.”

There is some indication that MC Duke wasn’t simply jumping on a bandwagon with his indignation. “Miracles” dropped in ’88 and already showed him inclined to kick knowledge. At the same time “Miracles” signals still a transitory phase for the artist and his producer Simon Harris as filtered vocals and a lightfooted beat take the track in a dance direction, estranging the rhymes from the beat. In contrast, he’s keen to create a connection with the listener on “We Got to Work,” confronting him with everyday situations he can relate to. The rapping has a Fresh Prince bent and the track a bubbly pop touch to it, but Duke really goes into detail on the subject and not only turns the tune (with the help of the studio crew chanting the chorus with full committment) into a veritable worker’s song, he also ends it on a philosophical note no self-help book could put better.

The message of “Gotta Get Your Own” is similar but the track is hardcore hip-hop at its finest, a rare groove embedded in dense percussion while the MC’s spitfire rapping bursts with attitude. Duke and his team also test his crossover potential with the swingbeat-influenced “For the Girls” and “Throw Your Hands in the Air.” “For the Girls” includes the preemtive argument “To a hardcore fan, don’t think I’m slippin’ / This ain’t a love song and I ain’t singin’,” but he’s not particularly convincing “payin’ respects to the female sex” when he follows it up with a cheap “But if a bitch be ugly, I’ma scream out ‘Next!'” Reverting back to a more American accent doesn’t help either.

These minor missteps don’t compromise the timeless hip-hop attitude that makes a cut like “I’m Riffin'” one of the most iconic moments of early British rap. “I’m Riffin'” (subtitled ‘English Rasta’ on the single) is intense, unfiltered expression on every level. A sweeping Jesse Jackson sound bite opens the track, segueing into a kick-ass taste of the beat to come that simultaneously builds anticipation for the raps, loudly and clearly announcing that what you’re about to hear isn’t some playground rapping. Now the rhyming isn’t necessarily eloquent, but he’s emceeing that thing, controlling the proceedings with that rhythmic staccato that makes rap a language all of its own, hurling his words at the world with the urgency of a Chuck D or an L.L. Cool J or late ’80s luminaries Kool Keith and Chill Rob G – or even the soon-to-emerge 2Pac. “I’m Riffin'” is also evidence of Simon Harris’ craftmanship behind the boards, who really knew how to put those hard but funky tracks together. The way he weaves the Equals sample into the pounding percussion is monumental.

Under the handle Double H Productions MC Duke and his DJ Leader 1 actually worked with Harris on nearly every track. The three made another album together, 1991’s “Return of the Dread-I,” but by that time the first heyday of UK hip-hop was already winding down. In a recent interview Duke remembers touring Europe with American headliners and stunnedly witnessing the acid house craze upon returning home. Make no mistake about it, rappers like MC Duke and albums like “Organised Rhyme” are being remembered, but the music scene itself seems to forget as quickly as it moves forward. Duke and Leader 1 were actually right there at the intersection between hip-hop and jungle in the early ’90s, releasing independent singles in both styles and even operating the label that gave Roots Manuva (as part of IQ Procedure) his first shot. These tunes were, in their respective format and fashion, very different from this album’s four-verse songs, and yet there isn’t the slightest doubt that those early years in UK hip-hop were essential to the development of a distinct urban UK scene that has seen so many manifestations since.

Having been called ‘British rap’s first essential longplayer,’ “Organised Rhyme” was lovingly reissued in 2010 on Cherry Red imprint Original Dope, containing four recent rap tracks from the Duke. A serious comeback is unlikely, but it was nice to see people still caring about this UK hip-hop artefact and the artist himself still caring about the artform. His contemporaries would record bigger and better albums, but in 1989, going well into 1990, MC Duke was the British rap star to beat.