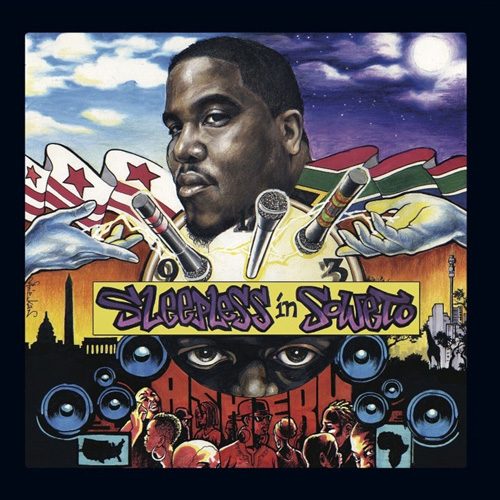

If you take a look at Asheru’s discography you might think he’s a bit of an insomniac. The Unspoken Heard member released Sleepless In D.C. in 2006, quickly following it with Sleepless in Japan. Now, seven years, two Boondocks mixtapes, and an EP later, he’s back to being up late again with Sleepless in Soweto.

This time around Asheru is tackling a topic that’s especially close to his heart, as he looks to use hip-hop to show the world the unique bonds between African-Americans and Africans. RapReviews caught up with Asheru to find out more about the project, including what led to his first visit to Africa, and what he’s learned during his numerous extended stays there. Asheru also discussed which influences of African hip-hop he hopes rubs off on American hip-hop, and his experience opening for Kanye West.

Adam Bernard: Let’s talk about the new album, Sleepless in Soweto. You recorded it while traveling between D.C. and South Africa. What were the kinds of things you saw that inspired you?

Asheru: Really, just seeing people who look like they could be member of my family, on the other side of the world, that were into hip-hop music and culture the same way that I am. I knew that it was global, I knew that hip-hop was everywhere, and I’d seen it expressed in various places, but it just really all connected, and clicked, for me when I was there. The reception to what I was doing, people who were fans of the Unspoken Heard stuff from back in the day, people who love The Boondocks currently, I had a lot of hip-hop heads, they were coming up to me, and they knew about my catalog of work, and all of that. It was just really special for me. To be there, and to be so welcomed by the hip-hop community, immediately immersed in it, and recording, and doing shows with folks, all of that, I kinda changed the way that I looked at what I was doing as an emcee, as an artist, and it made me really realize that I could, as an independent artist, push, and promote, and market my music in any way, to any corner of the world that I want to. I had done the Sleepless in D.C. project in ‘06, I had done the Sleepless in Japan version, so it just kinda all made sense for me to do one that was based, and dedicated to, the continent of Africa, and specifically the country of South Africa.

AB: How many trips did this entail?

A: I’ve gone back and forth maybe seven times in the last three years. I would go for like a month, come back home, go for another month, off and on. I did a lot, I saw a lot, I worked with a lot of really dope cats. I feel like, where I am now in my life, and in my career, this album is just another expression of my growth, and where I am now.

AB: First of all, you must have frequent flyer miles out the yin yang at this point.

A: {*laughs*} Right. Exactly. Yeah, I do.

AB: When you were staying there for a month at a time, that’s too long to stay at a hotel, so were you renting a house, or staying with friends?

A: Actually, I was living with a brother named HHP, who is a huge artist in South Africa. I hosted him when he came to DC, it was myself and a couple other folks from another organization, and from his visit here he got inspired, and was like, “I will bring you to South Africa. I gotta show you the motherland from my vantage point.” Right after that trip from DC, maybe about three weeks later, I was in South Africa, I was touching down and getting off an airplane in Johannesburg. It just happened like that. After that first trip these other things spun out of it. We recorded two seasons of a TV show down there. We performed during World Cup. We did a bunch of different shows in Cape Town, Johannesburg, I did the Red Bull Music Academy, I opened for Kanye. Stuff that I wouldn’t have normally done here, I kind of ended up just falling into every time I traveled over there. That was another big part of it.

AB: Was your experience opening for Kanye a good one?

A: Yeah, it was at the Coca Cola Stadium, so it was like a 20,000 seater. It was good because of how huge the audience was, and I was part of a group of South African emcees, so it was almost like a tribute to South African hip-hop. You had guys who were like veterans down there, like Dumi, and Proverb, and HHP, these guys are like heroes in the hip-hop community, so to be a part of their performance, and to do my little thing, it was great. The reason why I was brought there, we put a single out maybe a year and a half ago, called “Dreamgirl,” which was on HHP’s last album. The song was a hit, it got a lot of radio play, a lot of video spins, so it was a big record, so to be able to go down, and do that record at the venue, was awesome.

AB: And you mentioned a television show you filmed two seasons of. What was going on with that?

A: HHP had a show called The Respect Show. When I went down the first two, or three, times my band came with me, and the band ended up getting picked up as like a house band for the television show. Kind of like how The Roots are the band for Jimmy Fallon. They filmed about 26 episodes with different performers, and different guests. It’s basically a 30 minute talk show that was broadcast down in South Africa. I went on as a guest.

A: {*laughs*} I have my family here, I have my organization, and the school stuff that I’m doing. I work at a high school currently, too, so I had other stuff that I had to come back to, and tend to, but I have thought about packing everything up and moving. I have definitely given that some serious thought.

AB: I’ve read the goal of the album is to highlight the unique bonds between African-Americans and Africans through hip-hop. In what ways do you think you accomplished that goal?

A: Just from conversations that I’ve had about our opinions of Africa. When I work with youth, and I ask them what comes to mind when I say the word Africa, it’s generally a negative connotation. When I was in Africa I noticed that some of the conversations that I was having with people were based around a stereotype, or an idea of what it means to be African-American, so I saw both sides of how we both kind of have a skewed view of each other, and I think that it’s detrimental to our ever binding, and coming together, because we automatically go into it with these assumptions that aren’t always true. On the album a lot of the themes, and the concepts, and the lyrics, are around that connection, and the irony of being Black, but not really having a nationality to speak of. A South African would say, “I’m South African,” they don’t say, “I’m Black,” but in America we don’t say, “I’m American,” we say, “I’m Black.” Just seeing that dichotomy of how race plays a factor in our identities, and how it’s expressed in our music. Even the concepts and the themes that a typical African, or South African, emcee would rap about, they aren’t the same as what a typical American would rap about. It’s totally different, actually. Now it’s starting to be a thing where they’re picking up some of those (American) traits, and I see our influence creeping in, and I’m kinda hoping that it doesn’t, to be honest.

For example, it’s not typical for a South African artist to mention women as bitches, but it’s starting to happen now and it’s totally because here (in America) we say bitches all the time. I want it to go the other way. I would like to see us doing more of our cultural retention, and (investigating) where we came from, and identifying with some of those things when we look to Africa. Africa is where the drum started, hip-hop is very drum driven, so it’s naturally connected. I want us to culturally connect. Some of the references that I made in the music, some of the beats that we use, like South African house music on one of the tracks, I use Afro-Beat on another track, I might say a South African slang word mixed in to what I’m saying, just as a cultural reference, but it’s really making an effort to connect. Also, the biggest part is you have South African artists who are rapping in English and a hybrid of one of their native tongues, which is Setswana, so HHP, when you hear him on the album, he’s rhyming in English and Setswana, but we don’t translate it, it’s just a feeling that you get from him flowin that you know what he’s saying even if you don’t specifically know what he’s saying. That’s all intentional, and trying to show how we are all connected through this music.

A: Right, and that’s my era, as well. I grew up wearing Africa medallions, and learning about my history from listening to artists that really made me want to go look further, and investigate, and do knowledge on who these historical figures (were), and the references that they were making. That was very much a big part of my development as an emcee. In a way, I feel like I’m kind of going back to that. I’m going back to my roots of how I was introduced to hip-hop, and making it available, and viable, for the newer audiences. I want my kids to listen to this. My students that I work with can listen to this album and pull something from it. I don’t want it to just be something that I’m trying to do to keep up with these various rappers of the world who are popular right now. It’s not intended to do that. It’s intended to kinda leave a time capsule of where we are right now in 2013, and the condition of the world, and how we are as people in America, in South Africa, in different parts of the world, and what’s really going on. That was an underlying push behind all of this, really returning back to that cultural part of the era of hip-hop we came out of.

AB: Earlier you mentioned teaching high school, and I know you created Educational Lyrics LLC in 2005. What do you consider to be your greatest accomplishments in that field?

A: I am still expanding. I’m still working. Now it’s moving into working with Universities, and teacher prep programs, and speaking at conferences about how hip-hop, and the youth media culture, can be integrated into the classrooms. It’s spreading and expanding further than I ever really imagined. (I’m) now working with the NEA (National Education Association), working with Howard University, working with RapGenius, to integrate our culture into the classroom and show that there is some value in the words and the works of our community and our generation.

AB: That’s fantastic! Being that our time is almost up, is there anything else you’d like to add?

A: I plan to go back (to Africa) in early March to promote the album, and we’re doing an extended version of the album with some remixes and new featured guests. I just want people to support the project. Their support also goes towards the other programs that Guerrilla Arts is doing, working with the youth in our after school programs, in our during-the-day camps, our teacher recruitment programs, our artist training and recruitment programs. All of those things are tied together, my work and my music are all connected, so supporting this album is really supporting Guerilla Arts and all of the other community work that we’re doing. You’re not just putting $10 on a rapper. I want people to understand that, because it is expanding, and I feel like the time is now for us to support. I hear people say, “Hip-hop is dead. It’s all bullshit now,” and, “I’m so tired of what I’m seeing and hearing.” Well, this is an opportunity to step away from that, and the only way that it’s gonna help us is for people to support it, and to get behind it, and to help spread the word, so I really need everyone’s support. If you really love hip-hop made in the ways of the masters, from that golden era, but updated with a new twist, I really make an effort not to be preachy, or to be dull, so the music is very moving.

AB: It’s a funky and fun album.

A: Right, I’m trying to make it funky and fun, and not super preachy and boring, so I want people to get behind it and support it, and we’re gonna keep making it as long as we can. We have new project already in the works. (Nelson) Mandela just passing was a big blow to the whole country, so I’m sure that there are going to be other things that come out of that, other inspirations, or what have you, but like I tell everybody, Africa is the future, so I just want us to start directing our energies toward the continent and see how we can remain connected.