As a title, “Ghetto Millionaire” makes the same statement as the Big Tymers’ “Hood Rich,” Lil Keke’s “Platinum in Da Ghetto,” Slim Thug’s “Already Platinum,” 5th Ward Weebie’s “Ghetto Platinum,” WC’s “Ghetto Heisman,” Pras’ “Ghetto Supastar,” or Mystikal’s “Ghetto Fabulous” – except that Royal Flush’s is the oldest album in this series.

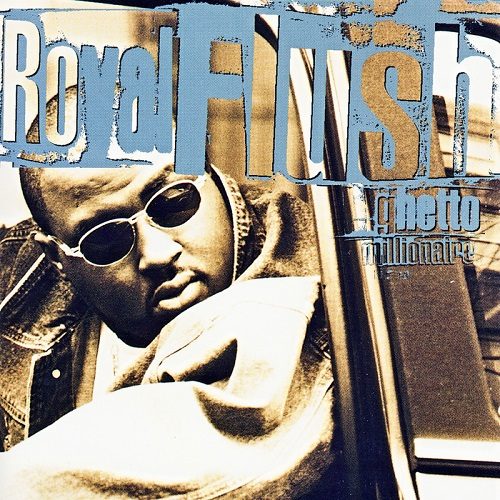

There is no title track that would further explain the idea of a ‘ghetto millionaire,’ but to anybody familiar with rap the dichotomy isn’t really one as rappers have for the longest highlighted these special hood honors that include but aren’t limited to financial success. When his debut came out in 1997, Royal Flush was part of a major trend of New York acts with a purported background in illegal business. He came up under the wings of fellow Queens representative Mic Geronimo, on whose 1995 effort “The Natural” he was featured half a dozen times. “Ghetto Millionaire” was released on the same label, and Geronimo returned the favor with three cameos. The two albums also share a number of producers, who are one reason Royal Flush’s debut is a noteworthy specimen of late ’90s East Coast rap.

Another one of Flush’s connects were Capone-N-Noreaga, and two of his singles were directly related to “The War Report.” With “Iced Down Medallions” E.Z. Elpee tries his hands at an epic production in the vein of the “T.O.N.Y. (Top of New York)” beat as Flush unapologetically spins his dreams of being an underworld figure that still doesn’t lose sight of reality: “Watch jake / can’t go to jail with no cake / cause when I come home I got to live crazy straight.” It doesn’t take Noreaga’s hook to see the kinship, even though “Iced Down Medallions” doesn’t challenge “T.O.N.Y.” as one of 1997’s defining singles.

The other track closely related to Capone-N-Noreaga is “Worldwide.” In 1996, CNN, Mobb Deep and Tragedy reacted to Tha Dogg Pound’s “New York, New York” with “L.A., L.A.,” and the same year the Flushing representative made it clear that if nobody else, Queens would respond to subliminals: “How you let these cats shit on your residence? / With fake robberies, who shot who with no evidence […] Worldwide, worldwide, whenever beef is startin’ / keep your mind on Queens when the dogs start barkin’.” L.E.S. provides perhaps the album’s best beat, an ear-pricking piano/strings loop (more recently recreated by Harry Fraud for “I’m a Coke Boy”).

The rest of the beats don’t stand out as much and sometimes fall short of the name behind them, but they contribute to the contemplative, laid-back atmosphere of the album. Buckwild blesses the bluesy, sax-laced “Makin’ Moves,” Onyx producer Chyskillz goes into stealth mode on “International Currency,” and Da Beatminerz keep things equally low-key with the jazzy, Nas-sampling “Movin’ on Your Weak Productions.” Future big names Sha Money XL (then going by Sha-Self) and Hi-Tek make themselves heard, the former with the customary posse cut featuring Flush’s Wastlanz clique, “Conflict,” the later with the Roy Ayers/Mobb Deep hook-up “Shines.”

A product of its time, “Ghetto Millionaire” is influenced by the sound design especially of 1996. E.Z. Elpee and L.E.S. had already mastered the polished, plush soundscapes with Junior M.A.F.I.A.’s “Get Money” and AZ’s “Sugar Hill,” respectively, and while they aren’t on that same level, tracks like “What a Shame,” “Regulate,” “Family Problems,” “Reppin'” and Buckwild’s “I Been Gettin’ So Much $” and “Niggas Night Out” (with planned guest Mr. Cheeks presumably cut out) and two contributions by a certain Prince Kaysaan keep the ball rolling. But whenever we’re dealing with a typical release that stands for a specific trend but isn’t the paragon that defines the trend, it’s often the variations that stand out. “Worldwide” has already been mentioned, and the beat Flush himself puts together with his brother for “War” sounds like its sneakier co-defendant.

As an MC, Royal Flush trails behind his Queens cohorts without ever reaching their level. He doesn’t embarrass the legacy, but neither does he add to it. Sometimes he’s surprisingly clear, such as on the closing, cleverly titled “Dead Letter,” a heartfelt farewell to lost ones. “Shines” takes a closer look at those medallions and the trouble they can get you into. Concerned about the serious side of what 50 Cent would later use for comical effect in “How to Rob a Industry Nigga,” Flush comes to the conclusion, “I’m dyin’ over better things, not flooded pieces / Kids die for no reasons […] I wish we all wouldn’t wear it, even.” While Royal Flush reliably raps from a personal perspective, the story told in “Family Problems” is so intense it makes you wonder if it actually did happen to him. Meanwhile “Illiodic Shines” sees Flush and Geronimo team up to retaliate on a stick-up kid in a fictional scenario while Nore joins him on the jailhouse lament “What a Shame.”

“Ghetto Millionaire” is a typically-themed ’90s New York album, from the opening declaration that the artist isn’t dependent on music industry money (“I Been Gettin’ So Much $”) and that hustling is in his blood (“Can’t Help It”) to mob analogies (“It’s like a mob flick / speakin’ on some mob shit / Son marvelous, the god is confident / the black arsonist that’s always startin’ shit”) to bellicose threats and sincere regrets. Occasionally reminiscent of greater albums “The Natural” and “The War Report,” it largely eludes the grip of the jiggy era, but it is stuck in a slightly uncomfortable zone between commercial and underground – without the lyrical skill to elevate it beyond such issues. Nevertheless it’s Royal Flush’s naturally relaxed disposition that makes “Ghetto Millionaire” a smooth ride into an admittedly uncertain future.