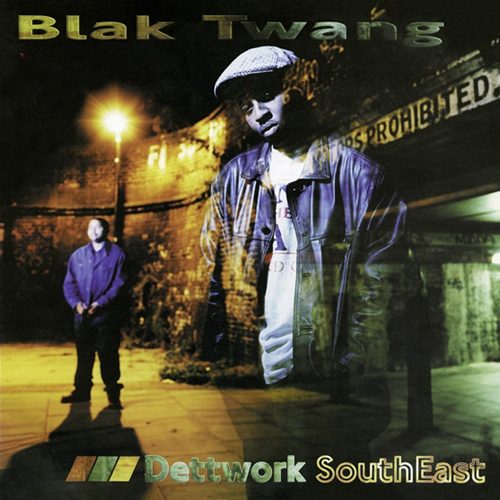

It’s the stuff legends are made of. A gifted up-and-coming rapper generates a tremendous buzz for himself and a debut that is recorded and ready to be released but doesn’t see an official release until almost 20 years later. “Dettwork SouthEast” has been around all these years, but as a bootleg it reached its most widespread distribution in old school tape dub form. So the 2014 edition of an album Blak Twang himself called (as early as 2002) an “unreleased classic,” which (now defunct) authority on the matter, Hip Hop Connection, ranked as the fifth best domestic hip-hop full-length of all time in 2007 and which the current promo advertises as an “un-released British masterpiece that has reached almost mythical status, and undoubtedly the holy grail of UK hip-hop,” is indeed an event.

In the mid-’90s, Blak Twang and “Dettwork SouthEast” could have filled the void left by the first generation of hip-hoppers in the United Kingdom who were denied a prolonged career. Not coincidentally, the album name, a play on regional rail section Network SouthEast and the artist’s own South East London stomping grounds (Deptford/Lewisham), paid tribute to the first family of London rap, D.E.T.T. Inc. (an acronym standing for Determination Endeavour Total Triumph), a loose collective that comprised, among others, London Posse, M.C. Mell’O’, Monie Love, Sparki, DJ Pogo and Cutmaster Swift. Blak Twang was poised to continue their legacy, while his stage name also referenced the term ‘UK Black’ (or as the 1990 debut of Soul II Soul singer Caron Wheeler spelled it, “UK Blak”) that marked an identity debate about what it means to be black and British.

Yet as a product of 1996, “Dettwork SouthEast” wasn’t only influenced by the Afrocentric and often militant stylings of the turn of the decade, it also reflected the somber, pensive aura of East Coast rap of the preceding years. Anyone familiar with 1994, 1995 albums in the range between Onyx and Hard 2 Obtain will recognize the soundscapes found on Blak Twang’s debut. Heavy, sluggish drums, thick basslines and filtered but persistent jazzy and soulful loops combine to form some sort of slow-mo boom bap that supports Blak Twang’s monotone growl that occasionally breaks into Caribbean-tinged chanting. The title track is attention-grabbing in comparison to the rest of the material, ominous, sharply plucked strings providing the track with bump as the rapper born Tony Olabode connects the dots on his personal London tour, with just a few hints of some secondary business he might be involved in. But the emphasis lies clearly on the artist watching his environment with both a knowing and a critical eye.

While he rarely deviates from the matter-of-fact tone, the moods of his songs vary. “Fearless,” penned under the impression of the racially motivated murder of student Stephen Lawrence, sees Twang bracing himself for eventual attacks on his physical and mental integrity. It’s one of several songs that not only present the 24-year-old as an unbreakable spirit but also contain spiritual undertones. While it doesn’t go beyond “Bless the mic like a baptism / in the name of the father, and the son and the rhythm” on the pugilistic “Tai Boxing” (he was also known as Taipanic at the time), “Crème de la Crop” reaches almost sermon-level intensity as he ruminates about the rap scene with vivid vocab. While on the subject of spirituality, the idea of karma appears in “Heads & Tales,” but as songwriter he puts his own spin on the morality play set in the streets of London.

Not every rapper reaches that next level of reflection when he portrays his surroundings. 1996 Blak Twang does. Using a wicked “Theme From Mahogany” interpolation for the hook, he unveils sinister schemes in “Don’t Let Dem Fool You” in a rather incisive manner:

“Everything they own is ill-gotten

That’s why society is rotten like that toilet in ‘Trainspotting’

Some graduatin’ from pickin’ cotton to pickin’ pockets

Out of nothin’, just keep it on the low like belly buttons

While you’re struttin’ and scammin’

dem mans is plottin’ and plannin’

Pull the wool over your eyes so you don’t know wa’s gwanin'”

For more head-on social commentary there’s “Real Estate” (a pun on the North American term). Like London Posse and Katch 22 before and others such as Skinnyman and Plan B after him, the “backstreets survivor” takes the opportunity to represent another side of Great Britain:

“My environment contains scenes of graphic violence

Single-parental guidance means more sirens

Joyridin’ with no provisional licence

leaves cars capsizin’ – and more moments of silence

It’s hell where I dwell, it ain’t hard to smell

Some youths even sell drugs outside my doorbell

Welcome to the real estate where everything is lethal

People lookin’ medieval, peepin’ from curtains to see you

Illegal transactions, makin’ money, no taxin’

Income Support – can’t afford food for thought

How could they expect your dole cheques to stretch for two weeks?

Tellin’ people to jobseek? I tell ’em ‘Kiss my butt cheeks’

Most braids around my way won’t even stay in school

They’d rather be in a cafe burnin’ and playin’ pool

Displayin’ tools, disobeyin’ rules and that

Makin’ moves, bobbin’ and weavin’, robbin’ and thievin’ jewels

It’s like that”

These days Blak Twang likes to stress that “Dettwork SouthEast” accurately reflects his life at the time. It’s a credible claim to all who are now witness to it. Still there’s the noticeable intent to translate themes of American rap. And yet for all the talk about ‘dead presidents’ on US shores, (not counting group dead prez) the menacing undertone of the term was never as distinguishable as on “Queen’s Head,” which Taipanic and partner in rhyme Roots Manuva want to see on their platter. At the very least, Blak Twang always instills the familiar story he has to tell with homegrown and personal flavor, whether the Queens’ portraits grace his currency instead of those of American presidents or cannabis is called ‘draw’ in “Entrepreneurs.” Even the reenactment of an embarrassing memory at the beginning of “Growing Up” has a UK ring to it. (Or maybe it’s just the sheer honesty.) Of course there are also phrasings that are easy to connect with London, such as “I’m in the house like a squatter” or “Old fogeys with cold bogeys and runny noses lookin’ hopeless.”

Statements regarding linguistics and lyricism are frequent, evidence of Blak Twang’s self-perception as a man of the word. The music is bound to play second fiddle in a situation like this. The production of the album, handled by DJ Rumple, V.R.S. and Taipanic himself, is expertedly done and several times even outstanding, but it’s also undeniably repetitive and bleak and bleary, especially in a 2014 context. What holds it together musically is Blak’s flawless baritone flow and the melodic vocal outbursts, also courtesy of guests Roots Manuva, Fallacy, and Seanie T. Lyrically he doesn’t break any mold but is more eloquent (and educated) than most of the overseas peers he evokes. There’s not one moment of plain stupidity (and they’re pretty much inevitable on ’90s rap records), and even the cliché James Bond references of “Rhyming Is Forever” are compensated by the seriousness of the track.

So what now of the legendary, perhaps even mythical status of this album? While that aura will probably clear now that it’s finally out, we now have official proof that a lot of it was definitely deserved. There are a good handful of classic UK rap songs (“Dettwork SouthEast,” “Fearless,” “Queen’s Head,” “Don’t Let Dem Fool You,” “Paralytic Monkey”) gathered on a strong album. This is a very condensed and intense form of rap, so it’s not for everyone, but for those with a long cherished affinity for UK hip-hop, the fortunate release of “Dettwork SouthEast” is a revelation as well as a reward.