According to a 2014 Nielsen report, jazz is the least popular genre in America. Jazz made up just 1.4% of all albums sold in 2014, compared with 17% for hip-hop, 30% for rock, and 14% for pop. To put that in perspective, the 5.2 million jazz albums sold in the U.S. in 2014 is only a little more than the total sales of the “Frozen” soundtrack alone. To most people, jazz is background music that all sounds the same, music you might hear at a reception or cafe, but certainly wouldn’t pay to listen to. From my own perspective as a jazz fan who doesn’t listen to contemporary jazz, I think there are a few reasons for this. Jazz has struggled with finding a broader voice in the past twenty years. Unlike metal, another genre that has faded from mainstream favor, there isn’t a robust jazz underground. The jazz that is out there is either avant-garde noise, easy listening smooth jazz, or fiercely traditionalist. It hasn’t found a way to connect with younger audiences, or audiences beyond dedicated jazz heads. Music tastemaker Pitchfork covers experimental music, modern classical music, but almost no jazz. Myself, I am a huge jazz fan, but I almost never listen to anything contemporary. I have hundreds of jazz albums, but only two of them were recorded within the last thirty years.

And yet jazz has the potential to speak to current audiences. People still have an appetite for instrumental music, as the success of EDM in recent years proves. People also have an appetite for music that challenges traditional song structures, whether it be in the form of composers like Max Richter, electronic artists like Oneohtrix Never, or extreme metal artists like Liturgy. There is also still an audience for music that swings and grooves, both from the jam band end of the spectrum and the funk and R&B end.

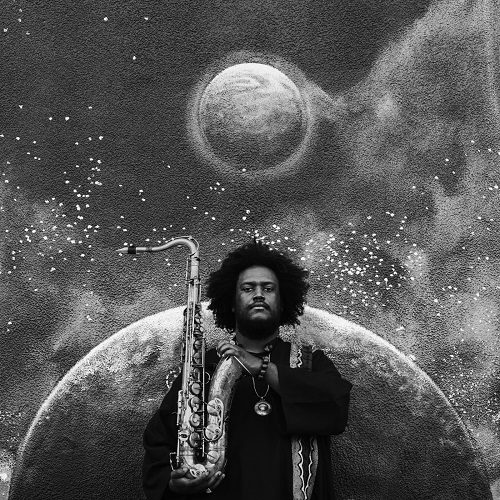

Enter Kamasi Washington and the West Coast Get Down. They are a group of 10 L.A.-based jazz performers who all grew up together playing in high school. Many of them had parents or music teachers who were session musicians in funk and R&B bands, so grew up surrounded by music. I heard of Kamasi for the same reason most people heard of him: he played on Kendrick Lamar’s new album, and his album came out on Flying Lotus’s Brainfeeder label. (It’s no coincidence that Kamasi is co-signed by Flying Lotus; “You’re Dead!” was basically a jazz album). From that background, I was expecting “The Epic” to have a heavy hip-hop or electronica influence. It doesn’t. What it does have is a scope and power that is beyond almost any jazz album I’ve heard since John Coltrane’s later work or Miles Davis’s fusion albums in the 70s. In short, it is one of the best jazz albums I’ve ever heard.

The music on “Epic” was recorded in December 2011. Kamasi and the other musicians did a month of recording sessions, focusing on different band leaders, which resulted in 190 songs. 45 of these were Kamasi’s, which he in turn pared down to the 17 that appear on the three-disc and aptly named “The Epic.” This is a long, intense album. Many of the songs are over ten minutes long, and none of them are under six minutes. The band excels at building to climactic crescendos, and the longer songs often have multiple builds and releases. It is a dense, layered album. There’s a 32-piece orchestra. There’s a choir. Vocalist Patrice Quinn sings on several songs. It’s a huge album, and a lot of music to try to digest at once.

Musically, “The Epic” has almost nothing to do with electronica or hip-hop, and a lot to do with funk, 70s jazz fusion, and late 60s jazz by the likes of Pharoah Sanders. It has the audacity and grandness of jazz at the turn of the 70s, when Miles was doing “Bitches Brew” and 30-minute long songs about the nature of the universe were de rigeur, only without the acid-damaged sloppiness of that period. “The Epic” is long, but it is also focused. It rarely devolves into noise, although Kamasi’s tenor saxophone occasionally screeches or squawks during solos. There is a strong melodic imprint throughout the album, and even at its most chaotic it never goes into free jazz territory. It’s at times reminiscent of John Coltrane’s “Ascension” only in its unrelenting intensity.

Kamasi has played with Chaka Khan and Raphael Saadiq, and there is a heavy funk and R&B swing to “The Epic.” This grounds the album and makes it more accessible for a non-jazz audience, while still being jazz. “The Epic” is funky, it’s groovy, and it has a solid rhythm section. There’s a rock aggression to the drums, although they maintain the swing of jazz. There’s also a playfulness to the music that makes it constantly inviting. “The Epic” is in many ways a protest album, but it maintains a sense of joy and hope that keeps the listener rooting for it. “Leroy and Lanisha,” for example, has a nice easy groove that is contrasted by Kamasi’s almost angry solos. “Re Run Home” has a latin feel, with some funky bass thrown in for good measure. Then they fall back into the nice easy swing of the standard “Cherokee.”

The size of the album, while daunting, is also to its advantage. With two drummers, two bassists (including Thundercat), and a whole mess of other musicians and singers, “The Epic” has an incredibly full and rich sound. The band is under no pressure to truncate their solos, or trim down their ideas. Remarkably, there is very little fat or filler on the three discs. None of the songs feel like they could have been left off, and the songs don’t drag on, even when they are approaching the fourteen-minute mark.

As I mentioned before, “The Epic” is to some extent a protest album. It feels part of a thematic, sonic, and aesthetic whole with D’Angelo’s “Black Messiah” and Kendrick’s “To Pimp A Butterfly,” from the references to 70s African-American culture to the black-and-white album covers. The music is often angry and sad, but always maintains a sense of hope and celebration. The few songs with lyrics on “The Epic” are celebratory. “Cherokee” is about a Native American warrior. “Henrietta Our Hero,” possibly about Henrietta Lacks, celebrates “our hero, shining fearless and bright.” “Malcom’s Theme” turns Ozzie Davis’s eulogy for Malcom X into a song, and ends it with a quote from Malcolm himself calling for religious and racial tolerance. On “The Rhythm Changes,” Quinn sings:

“Our love, our beauty, our genius

Our work, our triumph, our glory

Won’t worry what happened before me

I’m here”

What I love about “The Epic” is how successfully it builds on the history of jazz music while making it contemporary. It is an album that pushes boundaries and yet is always listenable and relatable, even at its most intricate and complex. It never feels too smooth, too noisy, too noodly, or too traditional. It takes chances and succeeds at every attempt. It’s a jazz album for people that think they don’t like jazz albums, and one that I hope will help revitalize the genre.