Saafir went into the game prepared like few others of his generation. He snatched The Source’s Unsigned Hype honors in August 1992, he interned at Digital Underground, appearing on Raw Fusion’s “Live From The Styleetron” and D.U.’s “The Body-Hat Syndrome,” his acquaintance with rising star Tupac Shakur landed him a role in one of the most storied encounters between Hollywood and the hood, the Hughes Brothers’ ‘Menace II Society.’ But if that would make you expect a polished debut – on the Quincy Jones-founded Qwest Records, nonetheless – that successfully positions itself in the 1994 market – you’re in for a surprise. “Boxcar Sessions” is a bulky something with its own structure, surface and sound. Like Ben Grimm becoming The Thing, as Saafir the Saucee Nomad, Reggie Gibson transforms himself in a strong-willed, sometimes cheeky, sometimes contemplative character with uncertain superpowers.

Saafir’s debut has to be considered in the climate of 1994, the tail end of the creative peak of the earlier 1990s, when rappers were often competing for the most original vocal performance. In terms of exposure, the year may have belonged to MC’s with more consumer-friendly flows such as Snoop Doggy Dogg, Warren G, Nas and The Notorious B.I.G., but the scene was just as populated by rappers with highly idiosyncratic deliveries, from individuals like Craig Mack and Keith Murray to groups that presented a wide range of rap rhythms such as the Wu-Tang Clan, the Fugees, Bone Thugs-N-Harmony or Freestyle Fellowship. Rolling with a crew of his own – the elusive Hobo Junction – and representing Oakland, CA, Saafir could have been expected to either choose the rap career model pimp or gangster, yet his distinctly technical approach is part of the emergence of West Coast backpacker rap, complete with a natural consideration of graffiti culture, from the album title to writer Mike ‘Dream’ Francisco shouting out a few of his colleagues.

Comparing “Boxcar Sessions” to Saafir’s 1992 demo and his 1993 Digital Underground cameo, there’s a noticeable shift towards the abstract, both lyrically and vocally. 1994 Saafir raps in a sluggish staccato that some might interpret as stumbling over the beat. But take a closer listen and witness an MC searching for, striving for control. He devises an interesting start-stop flow whose pace is sometimes dictated by rhymes or word associations but remains just as often impenetrable. Saafir prefers to remain an enigma to a certain extent, inviting you to “see if you can find the lost treasure through measures in bars.” This concluding a track called “Bent,” one of several songs that are akin to a trip, dreamlike, seemingly deranged, possibly drug-induced. Coming from a rapper who claims to be “high already on life” – which in turn he complements with the barely audible adlib “…and bomb.” Bottomline, “Boxcar Sessions” presents the world according to Saafir, filtered through personal perception. From outside, you’re witness to a howsoever different state of consciousness, lyrically channelled into the proverbial stream of consciousness.

Saafir’s signature track “Light Sleeper” pushes the perspective towards self-consciousness. Save for the Geto Boys masterpiece “Mind Playing Tricks on Me,” it was virtually unheard of for a rapper to begin a single with the words “I know I’m an emotionally disturbed person / People think I’m talkin’ to myself when I’m rehearsin’ / on the rhyme.” “Light Sleeper” can be seen as the psychoanalytical version of Nas’ Greek proverb paraphrase “I never sleep cause sleep is the cousin of death” or Inspectah Deck’s intent to “stay awake to the ways of the world cause shit is deep.” While for Nas it were existential dangers that made him evade sleep and Deck hinted at a metaphysical bigger picture, for Saafir the perils came also from within. “I don’t need psychology to see / the dichotomy in me,” he muses, engaging in a conflicting inner dialogue that ultimately brings him in the near-death vicinity of Nas:

“So what do it mean when I reach maturity

and still see that I’m not the mayor of my mayonnaise

the master of my millieu?

At least I have a swing, and a few things on my mind

It’s never a good nighty-night, just a rise ‘n shine

Why’s the rhyme so important?

Why do I have to be so potent

blow the mic a flow without chokin’?

I don’t – I’m arrogant and outspoken

Mouth no token, I’m just a roustabout

I have a house and clout – but I don’t come tight

But it’s routine, since few fiend for true hip-hop

It’s a trip when I drop my style – and forget it

And forget where I got it from

and how I got ’em sprung

Cause I’m stuck on myself

And I depend on my luck and wealth

for health matters

So I don’t explode with stress, I serve you an elf platter

They tell me that my shit is fatter than the first

But I’m a light-sleepin’ rapper in a hearse”

At its best moments, “Boxcar Sessions” is open to interpretation. The lyricism has to be taken in, even if it doesn’t always prove conclusive or insightful. “Battle Drill” is perhaps a touch too martial and monotonous, and “Worship the ‘D'” may be fairly elaborate as far as rap songs about male sexuality go but possible headnodding is likely to be ascribed to the banging beat. “Swig of the Stew” is an early teaser for Saafir’s curious masculine-nerdy mixture, including everything from culinary and sexual metaphors to relatable digs at competition (“It sounds numb… has no feel… inorganic synthesis”), but when he claims to provide “tourniquets for broken English” you can’t help but think that if any breaking of language is being done, it’s on Saafir’s part. By the same token, doing damage and catching wreck were once code for a rap performance worthy of praise, so in some ways Saafir totally operates within a certain tradition of rap.

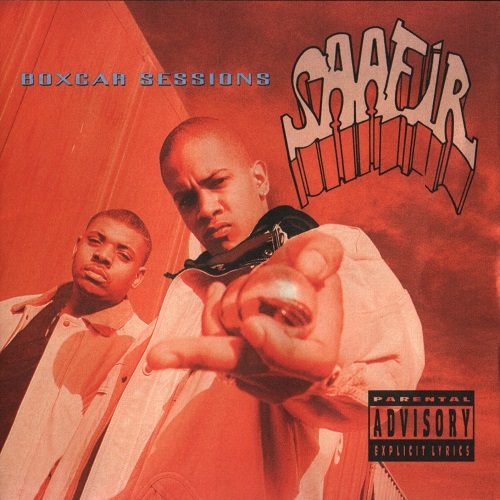

Nonetheless the Saucee Nomad makes sure you don’t compare him to another, calling himself “impervious,” “identical to none” and “the Hunchback of Oakland” and setting himself apart with allusive lines like “I try and try to tell fools / that I been through hell and my tools ain’t the same as yours.” Let us also consider that on the cover of “Boxcar Sessions” Saafir (accompanied by his DJ Jay-Z) is shown holding a pair of Chinese meditation balls in his hand while extending the middle finger of the same hand.

As it should, there’s no clear division between yin and yang on “Boxcar Sessions.” What can be differentiated is the more straightforward song material. “Playa Hayta,” for instance, although at the time the infamous term was still a new entry in hip-hop’s vernacular and J-Groove makes the Big Daddy Kane samples sound as if they came from Saafir himself. “Can-U-Feel-Me?” – besides being proof that Saafir isn’t indifferent to how he comes across – serves up slices of everyday life and ends with a salute to slain Hobo Junction member Plan Bee. “Just Riden’,” a smooth, surprisingly modern sounding single, and “Hype Shit,” a car race turned car chase, both contain brief references to Saafir’s ‘Menace II Society’ fame as cousin Harold. The deeper side of Saafir manifests itself in the more abstract offerings, but there’s also “No Return (Goin’ Crazy),” an almost matter-of-fact account that marks his emancipation from the days when he was celebrating “The Return of the Crazy One” with Digital Underground’s Humpty Hump.

“Boxcar Sessions” is a protracted listening (the numerous skits don’t help). For the adventurous listener, however, it’s a travel back to a time when rap was still exploring new terrain. What makes Saafir’s debut ultimately worthwhile is that it isn’t a purely intellectual exercise. He’s more of a technician than a theorist. He takes a leap into the unknown but finds out the first challenge is to ride the sturdy, sometimes stubborn beats provided by Jay-Z and J-Groove. “It’s best you let me wander,” he begins one song, and as the Saucee Nomad wanders across West Oakland and through his mind at the same time, he creates a notable specimen of earlier ’90s hip-hop that despite a series of mental somersaults lands safely on the side of rational and down-to-earth.