If you were to compare rap artists in the US and the UK in 2016, those whose music actually takes them somewhere, you’d notice major differences in how they exert their form of expression. The ratio of technically virtuous rappers seems to be significantly higher in the UK at the moment. Surely there are varying definitions of rap skills, but if we take one that is easy to comprehend, a feature that to laymen makes rapping seem difficult – keeping up a high tempo at a rhythmically steady pace -, there are really not that many North American rappers anymore who specialize in that.

Across the big pond, in grime and hip-hop, as well as the intersections of both, rappers lately show a heightened awareness of the technical aspects of delivering a rap – articulation, intonation, flow and speed, and not to forget scripting lyrics that lend themselves to a dense and intense performance. Apart from an (officially inexistent) interaction between grime and UK hip-hop, one perennial influence is West Indian sound system culture (mainly on the side of grime), another is rap megastar Eminem (mainly on modern age UK hip-hop).

Dabbla currently argues from a hip-hop point of view, kicking off his maiden voyage with the line “Come, we resurrect that shit we fell in love with / but not include the popping stupid bottles in the club bit,” but his admittedly spectacular performance owes both to Eminem and grime/garage/ragga. If that sounds impressive, know that some of the negative aspects of such panting and posturing are also present. They include fans engaging in the rather pointless excercise of finding out which rapper ‘owned’ others on any track that features more than one vocalist. There’s also the phenomenon that the more rappers say, the less they have to say, which also applies to a certain degree here. And like Eminem, Dabbla is an acquired taste when it comes to his voice and in-your-faceness.

Not that we have an Eminem clone in Dabbla, but part of his strategy is to temper the steadily building up superiority on the mic with self-accusatory comments, which is definitely reminiscent of Marshall Mathers. On a larger scale of comparison, Dabbla is quite a character and entertaining in ways many who try to rap can only dream of. He promises spectacle and delivers on various occasions. On “Supermodified” his nimble tongue is guided by an alert mind, switching between verbal machine gun and precision rifle but never losing sight of the target – to bear witness to Dabbla’s expertise and experience:

“I been doin’ this since tape decks

Came in the game through the rave sets

Still wonderin’ what he’s gonna make next

Still slavin’ away for them pay cheques

Pavin’ a way with them brave steps

Makin’ my name on the same flex

While they’re wastin’ away at the apex”

While there are a number of extroverted tunes that offer the rapper as well as the listener escape, Dabbla regularly plants reflective bars. “PterodactILL” is not just a livewire track, it also contains the remarkable statement “I would love to be the man that you look up to / But I find it hard enough to meet my own expectations.” With just a little bit of concentration, you’ll be able to make out a philosophical undertone, even if the subject of it is largely limited to the rapper’s personal habits. But dropping a little bit of food for thought among all the spitting is important enough for him to open the album with the unusually calm, even cosy “Everything,” which comes to the surprisingly genuine conclusion “You might not like me – but I fucking love me / Everything that’s beautiful and everything that’s ugly.”

Yin and yang are not always perfectly balanced in Dabbla’s world, but they don’t go strictly seperate ways. On “Get It” he even extends an olive branch to opponents:

“Catch a middle finger symbol

Or we could just keep it simple

Sit down and eat some Pringles

Talk bullshit and spit some

waffle all over these instrumentals

while we’re gettin’ all weird and experimental”

With “Super Happy” he takes evident pleasure in kicking ass lyrically. Imagine the outspoken delight artists like Sean Price, the Beatnuts or KRS-One have derived from humiliating competition and top it off with a hook that expresses pure bliss and a bouncy beat and you have a rather special track. It’s that kind of musical expertise that also helps bring forth songs that probe a little bit deeper. “Butterfly” sees Dabbla wax existentially over bluesy production courtesy of Sumgii, his Iron Butterfly interpolation culminating in a soaring chorus. On “Psychoville” a breezy Roast Beatz melody lures Dabbla down the rabbit hole as he goes into a sequence of manic soliloquies. The album’s lyrical standout performance can be found on “Bad Continuity,” which reveals that Dabbla’s taunting rhetoric has a solid foundation in intimate knowledge of self.

The latter goes as far as Dabbla being able to predict his future on closer “Lifeline.” Nevertheless, “trying to put the fun back in this shit,” the London MC is a true rap entertainer, outgoing and outspoken, talking shit and talking sense in equal measure. He’s trying to connect with the listener, getting there, besides the vocal performance, with a musical backdrop longtime hip-hop listeners should feel at home with. Especially main producer GhostTown is a devoted student of different schools of production – “Everything” features Dilla drums, “Vomit” recalls the heydays of Timbaland, “Cheers” and “Incomparable” could blend into any Bay Area party, “PterodactILL” bounces up and down like a Ruff Ryders rhythm, while the hype “Stupid” plays at home. Other out-there beats come courtesy of Don Piper (“That There”) and Star.One (“Randeer”), inviting Dabbla to flex his flow even more than usually, while Tom Caruana’s dubby soundscapes (“Supermodified,” “Super Happy”) help smooth things out.

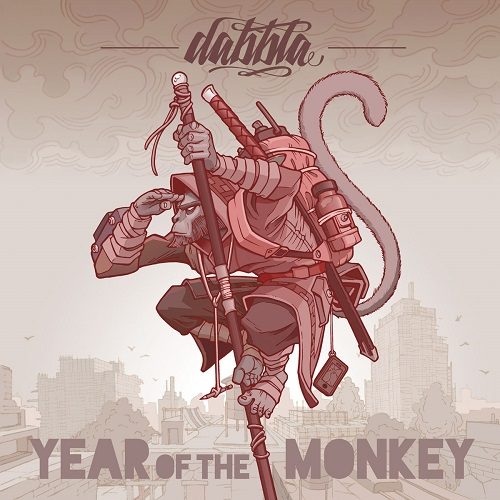

“Year of the Monkey” is a very playful and at the same time very solid release. As always liking a rapper is also a question of personal sympathy, and there’s some chance that in this case for our readership the good traits could outweigh the bad ones. Not least when compared to some of his guests, Dabbla comes across as a genuinely good-natured guy (check how he pulls off his part on “Penis For the Day” with decency). After listening to his solo debut you’ll know that “Dabbla’s a machine,” but you’ll also be aware that there’s a distinctly human touch to this rapping machine. To prove that point, you could quote from practically any track, but why not take the intentionally retarded “Randeer”:

“You don’t listen to a damn word anyway

Not one little thing that he ever say

If you did, then he would’ve became a heavyweight

With a bag full of memories and a bellyache”