For what it’s worth, Rosecrans Avenue, a major axis that runs from the Pacific coast to northern Orange County and crosses both Los Angeles and Compton, is a persistent landmark in Kendrick Lamar’s music. Those wondering how an artery that connects a number of different communities across a distance of 27.5 miles/44.3 kilometers can be a ‘landmark’ should be reminded that rap music has long elevated ‘the street’ to an entity that constitutes more than a microcosm of its own where much of the action goes down.

‘The street’ in rap is an empty canvas, reflecting anything the rappers project into it. It is the joker card that can be employer, partner, teacher, tempter, judge, traitor, enemy – or even a higher being that some subject themselves to (the street giveth and the street taketh away). Across often highly detailed lyrics, it almost becomes a persona of its own, occupying a more prominent place than traditional social spheres like family, work, school, love life, etc.

Rappers specify what the street is to them with varying precision, and the larger the settlement, the more likely they are to create focal points like the block, the corner, the trap, that their lyrics keep coming back to. Yet they can be just as precise (or unprecise) about bigger units like the hood, the turf, the ghetto. While far from a locally constricted artist, Kendrick Lamar strives for accurate geolocation (as well as personification), perhaps for the same reason as all other rappers – to lend credibility to his stories – perhaps because that’s just how he thinks about the world. Some are quick to generalize, others come to conclusions by way of examples.

With few rap songs intended to be exhaustive, most depict an extremely narrow section of the world, or, when they’re locatable, an extremely narrow sector of the world. Kendrick Lamar too, when he mentions Rosecrans Avenue, is talking about a stretch of road, not the entire thing. The genius of rap, however, has always been that it’s able to connect dots (on the map and otherwise), that it manages to paint a bigger picture within the given confines of its canvas, that it makes people all over the globe relate (with varying intensity, obviously), not simply across feelings like pop music so often does, but also across facts. One song from the boom years of street rap that aimed to be eye-opening (although with a wink) by offering a special kind of tour across the United Sates was DJ Quik’s “Jus Lyke Compton” from 1992. In it, the Comptonite recounts his earliest experiences on the road where he stumbles from one deja-vu into another, having to deal with the same gang drama as back home.

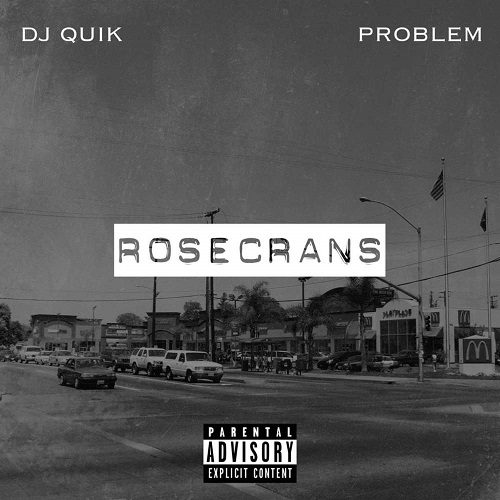

Critical acclaim came later for Quik, around 1995 with “Safe + Sound,” and while later releases failed to repeat the commercial success of his four gold albums in the ’90s (one even breaking the platinum mark), he continued to be regarded with favor by the receptive part of the public across albums like “Under Tha Influence” or his joint venture with Tha Dogg Pound’s Kurupt, “BlaQKout.” Seven years later “Rosecrans” sees Quik again share the billing with a West Coast vocalist. If Problem hasn’t been able to gain a foothold in the industry as the likes of Vince Staples or YG, teaming up with a legendary producer is without a doubt a step towards greater recognition.

“Rosecrans” reminds us that when DJ Quik summons folks to the studio, it’s not to simply play them beats and record raps with them. Quik takes an organic approach to making music – with people, not for people. Credited producers next to the two billed artists are a three-piece of people all named David dubbed SuperDave (which also includes Quik himself), Kenneth Crouch, Ray Keys, J.B. Minor, Alex Brown, Brent Jackson, and Polyester The Saint. Indeed “Rosecrans” also serves as a reminder that L.A. rap records (and by extension those of the greater Cali scene) are often substantially collaborative efforts that rely on existing infrastructure and know-how, perhaps in contrast to the ‘beatmaker meets MC’ partnership favored in regions where the East Coast influence dominates. Dr. Dre having half the world contribute to his interminable “Detox” project was just an extreme example of that philosophy. Quik is perhaps not the perfectionist Dre is, but he’s just as focused on music and would probably blindly co-sign the motto of the Doc’s longtime publishing company – Ain’t Nuthin’ Goin’ On But F***in’ Music.

There’s more going on, of course, Dre knows it, Quik knows it, Pac knew it, Kendrick knows it, and rap is here to report (or at least remind us of) what’s going on outside of the recording booth, all the while making sure that what leaves the studio isn’t utter garbage and bullshit but adheres to certain standards. April’s “Rosecrans” EP is only an accessory to L.A.’s bigger releases of 2016, yet a vital link between past and present. When Quik updates keystones of his discography (“Tonite” and “Quik’s Groove”) with the 10-minute “A New Nite/Rosecrans Groove,” he demonstrates what his generation has been doing all along – to add to what has been created before and make it fit the present situation. Kendrick Lamar doesn’t feature on “Rosecrans,” but he could very well. By the same token “Rosecrans” could be much more, but is also good for what it is.