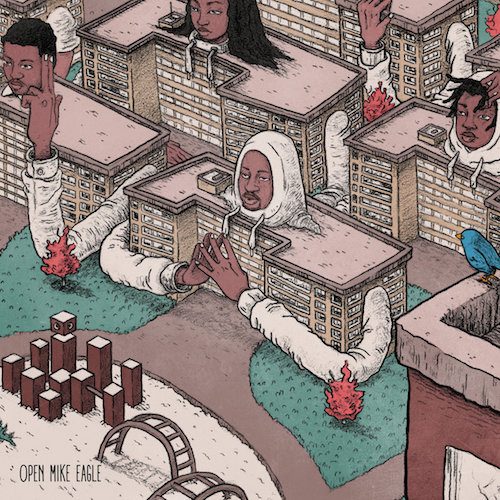

One of the most powerful things about hip-hop is the way that it gives a microphone to people from groups that aren’t often listened to in our society, and particularly people from neighborhoods that are often only talked about in terms of crime statistics. Hip-Hop was invented by a group of black and Hispanic kids who lived in the South Bronx, a part of New York City that most people wouldn’t want to drive through. Throughout its history hip-hop has given an audience to people from the most notorious areas in L.A., New Orleans, Houston, New York, Chicago, Gary, etc. L.A. rapper Open Mike Eagle continues this legacy with his latest album, “Brick Body Kids Still Daydream.” It is a eulogy to the Robert Taylor Homes in Chicago, which were demolished ten years ago. Open Mike uses hip-hop to tell the story of the people who lived in those homes, sharing a perspective that is rarely considered in the halls of city government or in the news. The album is full of nostalgia, love, compassion, heartbreak and rage. It’s one of the best things Open Mike Eagle has done in his career.

Open Mike is highly intelligent and highly educated, and he’s found a way to meld his intellectualism with hip-hop in a way that works. We’re talking 25 dollar words, obscure references, and challenging concepts all delivered in rhyme and on point. All of this means he can drop lines like “Y’all think it’s all good but it’s really a gradient” and make it sound legit.

The album opens up with the revenge fantasy “Legendary Iron Hood,” the video of which shows Mike getting revenge on gentrifiers. Throughout the album there is a sense of barely controlled despair and rage underneath Mike’s raps. “I fly in all my fantasies and die in all my dreams” he raps in “(How Could Anybody) Feel At Home.” On “No Selling (Uncle Butch Pretending It Don’t Hurt)” he raps over a woozy beat by Kenny Segal as a man trying to pretend everything is ok when it clearly isn’t:

“Crying ain’t my style cause I can smile good

I don’t take s*** personal

I don’t get jealous

You can leave my name off

You can misspell it

I ain’t with yelling

I ain’t even mad

I ain’t screaming catching feelings or breathing bad

My favorite phrase is so what

I’m stone cut and bad to the bone

No need to blow up

Calm before the storm or something

I ain’t cried since Ô94 or something”

That sense of woozy disorientation continues on “Happy Wasteland Day,” where Mike sing/raps over a slightly off guitar riff, asking, “Can we get one day without violence/Can we get one day without fear?” On “Brick Body Complex” he insists, “Don’t call me n*****/Or rapper/My motherf****** name is Michael Eagle.”

The compassion that Mike has for the residents of the Robert Taylor Homes comes through over and over on the album. “Daydreaming in the Projects” is a sweet tribute to the imagination and resilience of the kids growing up in the projects. “95 Radios” is a nostalgic look at trying to find hip-hop in a pre-internet world. He portrays the residents of the Robert Taylor Holmes as people with their own struggles, dreams, and hopes. They are not just statistics.

The album ends on the most powerful song, “My Auntie’s Building,” about the destruction of the building.

“They say America fights fair

But they won’t demolish your timeshare

Blew up my auntie’s building

Put out her great grandchildren

That building cost 10 million

Now an empty lot not filled in

It was people there and kids there

And drug dealers and church folk

Hit that s*** with a wrecking ball so hard

Thought the whole earth broke

All them people dispersed tho

Federal to commercial

State demolished my circle

I guess everywhere is my turf though

That’s the sound of them tearing my body down”

The beats are handled by Has-Lo, Exile, Illingsworth, Lo-Phi, Elos, Andrew Border, DJ Nobody, and Toylight. There is a fair amount of glitchy electronica, but there are also more straightforward loops. They compliment Open Mike’s melodic delivery and the wistful yet angry mood of the album. Sammus and Has-Lo also offer verses.

As a society, we all too often treat people that are poor and brown like problems to be solved rather than human beings. We criminalize and pathologize poverty and brownness. We act as if the terrible things that befall the poor are their own fault, and pass laws to make it ok to prey on them. “Brick Body Kids Still Daydream” is a powerful reminder of the humanity of those we choose to ignore.