A major website once noted that ‘Flint, Michigan isn’t exactly known for its rappers.’ While that may be true today, three rap acts put Flint on the map for the ’90s – Dayton Family, Top Authority and MC Breed. To me Flint, MI already had a familiar ring when I heard my first MC Breed song. I remembered the industrial town as the setting of 1989’s ‘Roger & Me,’ a satirical documentary directed by a certain Michael Moore. By the late ’80s, Flint and Genesee County had lost tens of thousands of jobs as General Motors restructured its manufacturing plants. GM went about it with so little social sensitivity that ‘Roger & Me’ easily attained the entertainment value of a fictional film. My local paper’s review read as follows (translated from German):

‘Accompanied only by a small team consisting of a cameraman and a sound man, author and director Michael Moore has documented the changes in his hometown Flint for three years. Thanks to his poignant, personal commentary the film becomes a blunt, sardonic social study of the rise and fall of a blue-collar town in de facto capitalism of the American variety.

The small town has been dominated by General Motors for decades. In 1937 workers fought for one of the first labor contracts in American history with a famous sit-down strike. During Reaganomics however, the solidarity of former times has eroded. As the corporation headed by chairman Roger B. Smith decides to shut down eleven plants in the ’80s and move the jobs to Mexico, the unions rally for a protest, but out of 30’000 who are out of work only four lonely souls show up.

Attempts to make the dying city interesting to tourists with luxurious hotels and a giant theme park ended in financial fiascos. The only safe jobs are offered by a new prison that had to be built because of the rising crime rate. The only person working to capacity next to the postal workers is Flint’s sheriff – almost daily he is forced to evict the unemployed who can’t pay their rent anymore.

A scripted tragicomedy couldn’t be more effective. Even on Christmas Eve three families are forced out with bag and baggage. Simultaneously, Roger B. Smith recites a touching Christmas poem with Dickens quotes and fobs off the film maker, who for years had inquired for an interview, with empty phrases.

Incidentally, at its place of origin the cinematically brilliant collage can’t be shown. It’s not that the authorities or the residents would not like the film – all movie theaters in Flint have been closed for some time now.’

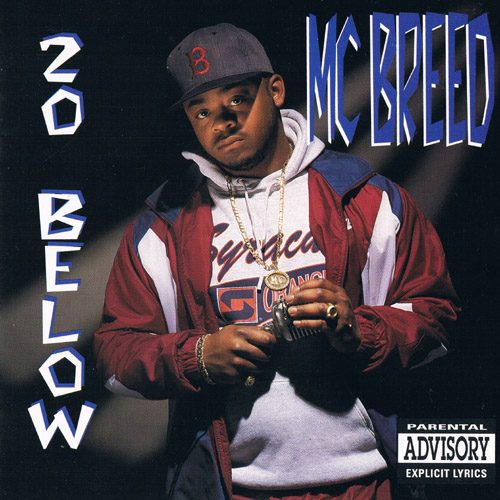

For Flint resident Eric Breed the future looked decidedly brighter. In 1991, his single “Ain’t No Future in Yo’ Frontin'” had reverberated across the hip-hop landscape, kicking off a career that made him a household name in rap and virtually the first to hold it down for the Midwest on a national level. “20 Below,” his sophomore 1992 effort, made a few ultimately unsuccessful charges towards commercial rap music, yet was, albeit not a career-defining moment, an important stepping stone towards establishing the MC Breed legacy.

It starts out strong with “Ain’t to Be F—ed With.” For the single release it was mitigated to “I Ain’t to Be Flexed With” and rewritten to make it radio-friendly, but either version convincingly delivers the message of Breed being able to fight his own fight. With his thick drawl and voice apparently hoarse from “arguing with them old knucklehead-ass niggas” (as the intro indicates) he spars with the pugilistic beat that incorporates elements of P-Funk and ragga while addressing typical concerns of a rapper rising to sudden fame: “I seen ’em hopin’ I fall but all in all stand tall.”

“Ain’t to Be F—ed/Flexed With” was a considered reaction to the success of “Ain’t No Future in Yo’ Frontin'” (a rapper-as-rhino metaphor even making a comeback in the more lyrical form of “I’m runnin’ through these suckers like a rhinoceros / What you sayin’ to E. Breed is preposterous”). Rather unnecessarily, the references to “Frontin'” don’t stop there. “Jealous Pimp” samples “Funky Worm” as well and rehashes certain turns of phrases, as does “No Frontin’ Allowed,” which lacks the melodic quality of its blueprint and finds the rapper stumbling forward (and mumbling, in the process), unable to maintain the casual demeanor he eventually came to embody. “Dis Mode” has the same problem. Breed’s deejaying partner Flash Technology opens the track with the same ‘Flash Gordon’ theme by Queen as Public Enemy’s “Terminator X to the Edge of Panic,” just to commix a jumbled collage of samples and cuts. It would be hard for any rapper to stay on top of such a mess, but Breed proves that he’s at least half serious even as the threat “Step to this, I won’t miss / cause I got a whole list of suckers I wanna dis” remains unfulfilled. DJ Flash takes a similar approach to his showcase “Flash’s Groove,” which despite running over 4 minutes is no “Quik’s Groove.” If Flash Technology really had “the SP-12 jumpin’ like a fire alarm” (as Breed suggests on “No Frontin’ Allowed”), it didn’t translate to the actual album. Which manages to sound sonically unfinished, a problem its lower-budget predecessor never had.

As it happens, the studio instrumentation of the title track does recall Breed’s first album more closely. Over a simulation of a gumshoe/gangster flick score (although not nearly enough exploited), Breed summons Vito Corleone and Kid Frost with his husky murmur while only bashfully hinting at a criminal past with “The B-r-double, I’ve never been in trouble / But I’ve sold more boulders than your boy Barney Rubble.” Bedrock may have been a nickname for Flint to Breed and his posse (see also “Ain’t to Be F—ed With”), but for some reason he didn’t run with it for “Life of a Flintstone,” so that rap had to wait five more years for the definite ‘Flintstones’ spoof courtesy of Oakland’s Seagram.

Surprisingly, the cuts who follow a radio format go down more smoothly. “Whenever You Want Me” may be forgettable rosy-cheeked romancing in a swingbeat suit, but “Little Child Running Wild” (whose folksy funk echoes Atlanta-based Arrested Development, who debuted the same year), makes sure to address both sexes with its cautionary commentary even as it concludes with the typical ‘Look here, boy, that’s what jail will be like’ warning that rap often has delivered. But the real treasure is “Ain’t Too Much Worried.” Supported by vocal ensemble Night & Day, Breed, who figures as something of a soulman version of Philadelphia’s Fresh Prince here, looks back on his past without regrets, because, that’s the message of the song, he can let bygones be bygones. Largely ignored when released as a single at the time, “Ain’t Too Much Worried” is a very winsome song – safe for the informal way he intends to care for his children, a mindset that may have come back to haunt him years later when he was locked up over unpaid child support. In all fairness, the situation likely arose due to a substantial drop in income. Before his untimely death in 2008, Breed’s health prospects were diminished by his financial situation, which is all the more tragic as, going by “20 Below,” one thing he seemed to have learned early on was making provisions for later in life. “Lavish-ass s–t ain’t gon’ last (…) You don’t believe me? Well, ask your boy Vanilla Ice,” he calls upon an unlikely (but probably credible) witness on “No Frontin’ Allowed,” while on “Dis Mode” he discerns that “at the end of every rainbow ain’t nothing but mud.”

A humorous tone runs beneath Breed’s early songs. At the same time he strikes you as the kind of rapper who has a lot of things on his mind – typically an optimal condition for good rap music. The “Great Depression”? “You’re in it,” he jokes, but while the music grooves along cheerfully he surveys the misery that surrounds him, including but not restricted to the one he witnesses in his hometown (“Shops close down, so now the city’s a crack pool / Shit’s so advanced even the vets must go back to school”). Although at the time of recording yet a danger that lied dormant, today’s listeners might be reminded of Flint’s recent water crisis when he raps, “There ain’t no money yet that they give away / Knowin’ you need water to live – but we must pay.”

One thing Breed was particularly concerned about in 1992 was the self-destruction of black communities, which he garners with a note of conspiracy theorism, but also criticism of neighborhood crack dealers (“No Frontin’ Allowed”). Hence, “20 Below” may be Breed’s most combative offering, but not really a defection to the gangster side as older opinions have suggested. What he, like so many rap personas who get misinterpreted as criminals, does is equip his rhetoric with martial imagery, see “20 Below”‘s metaphorical “Packin’ my knowledge like I’m packin’ a gat.” The Michigan MC would associate himself closely with the West and the South (rather than the East) in the coming years, but he would always maintain his uniquely own hospitable disposition. In that regard, the meditative “Be Myself,” true to its title (and explicitly inspired by Mary Jane), forecasts future full-length highlights like “Funkafied” and “To Da Beat Ch’All.” All in all “20 Below” is, like the rest of MC Breed’s discography, well worth revisiting.