Z-Ro gives new meaning to the term ‘socially conscious rap.’ The rapper, who as a young artist came to the compelling conclusion (in song form) “I Found Me,” proceeded to spend the rest of his career defining himself by his relationship with others, song after song, inadvertently proving the old saying right that no man is an island. If Z-Ro was on a mission to Mars, he’d still flip the bird at the rearview mirror while hollering a defiant “I don’t need y’all anyway.” Just to let you know. If that’s not being conscious of your social environment, I don’t know what is. The feelings he harbors are typically negative, to the effect that Z-Ro thinks he’s better off alone. That lone wolf angle has introduced a kind of character into the rap cabinet that is not only unique in its remarkable consistency but also distinguishes itself from most other outsiders by being portrayed as a winner, not a loser. Rather than a victim of social exclusion, he’s a maverick at his own will.

In the context of rap, this concept is bound to foster a fanbase eventually, because it lends the prevalent idea of superiority a human touch, a complicated note, an air of Wolverine or Batman. This makes Z-Ro actually less detached from reality than many of his more successful peers when with artistic sincerity and steadfastness he speaks about things average people can relate to. Yet when listening to his music, his audience experiences such emotions exclusively through the medium Z-Ro, who’s the pivotal point of the majority of his songs – and precisely not some Joe Shmoe. That’s where Z-Ro’s special brand of socially conscious rap risks becoming plain old ego trippin’.

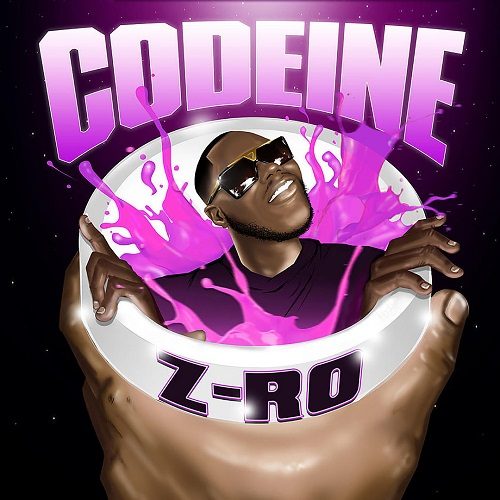

After twenty years Joseph McVey has rooted the Z-Ro character so deep in the trenches that the action is almost exclusively shot from the same angle. But perhaps it is exactly that familiarity with isolation and desolation that enables him to act as a shepherd to people in similar situations – and at times rise completely above, as he does on “You Ain’t Gotta Worry,” a particularly inspiring moment on his second 2017 full-length, “Codeine.”

Honestly, “Codeine” can be unpleasantly crude. The grotesque model of masculinity regurgitated in the first verse of “I Don’t F— With You” is the kind of bullshit we need to leave behind, and it’s not offset by the sappy, sentimental “Run This Down” that follows right behind. For what it’s worth, he loses his usual composure on tracks like “Never Been a Ho” and “My City,” lashing out at detractors aggressively.

Resentment and neuroses increasingly seem to preoccupy the personality of the rapper. It’s one thing to sit through an album and think you’re witness to a therapy session, it’s another to feel the urge to suggest one. If he took the focus off himself more often, he wouldn’t have to allude to situations and incidents that can eventually reflect badly on the actual artist. For example, there are so many instances where Ro distances himself from former partners that one has to wonder – are these dozens of different episodes or always the same ones that keep getting exploited? Neither is a particularly good look, for the simple fact that repetitive subject matter and the way it’s addressed suggest a limited artistic skill set.

Luckily for Z-Ro, rap is a genre that provides its practitioners with a full arsenal of arguments. One he puts forth at the very beginning of “Codeine,” sampling one of the patron saints of the South, Pimp C, on “Owe You Niggaz Shit.” “They like, ‘What ya doin’, why you still here?’ / I’m like, ‘Cuz this the rap game, bitch, I live here’,” he quips, ostensibly not going anywhere. Z-Ro is a relic of the collective dominance of southern MC’s (whose duration varies depending on your readiness to acknowledge said dominance), who never forgets to act in the interest of his home turf – “My City” laments the lack of support for the local scene, closer “Better Days” gives ample room to Street Military veteran Lil Flea, and “So Houston” features Lil Keke as Big Baby Flava croons one of these vintage off-kilter hooks and Ro lists the Houston rap ancestors that look benevolently down from the sky. Z-Ro is, surprise, really a good guy, and if you make an effort, “Codeine” will verify that (“Never Been a Ho” briefly, “You Would Too” extensively, “You Ain’t Gotta Worry” completely). But you will also find evidence that points in the other direction. Ultimately, Z-Ro is no more and no less stuck in his ways than everybody else. So you see that the human element never comes up short when it comes to Z-Ro.