“Ever since I talked at my very first party

I felt I could make myself somebody

It was something in my heart from the very start

I could see myself at the top of the chart

Rapping on the mic, making cold, cold cash

With a jockey spinning for me called DJ Flash

Signing autographs for the the young and old

Wearing big-time silver and solid gold

My name on the radio and in the magazine

My picture on the TV screen

It ain’t like that yet, but, huh, you’ll see

I got potential and you will agree

I’m coming up and I got a step above the rest

Cause I’m using that ladder they call success”

Melvin ‘Melle Mel’ Glover is unquestionably one of the artform’s most emblematic artists, a towering figure in the history of hip-hop, a thoughtful and visionary writer without whom the music and culture would lack a crucial stepping stone. The song cited above, 1979’s “Superappin'” by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, also featured the nucleus of what would become the seminal “The Message,” but as the quote shows, Melle Mel was not just a vanguard of socially conscious rap, at age 18 he was literally the first to articulate the potential held by this artform for its mouthpieces, the masters of ceremony. And he was possibly the first rapper to pen clear-headed, conclusive verses, as well as the first to claim supremacy over competition with conviction. These are essential rap methods that a myriad of others have since used more or less skilfully.

After Melle Mel, rap would never be the same again. He took it to the proverbial next level. And like all the greats, he was able to consolidate his role by simultaneously commenting on it. As he recapped a few years after “Superappin'” (and “The Message”) in “Step Off”:

“I was sittin’ on the corner just a-wastin’ my time

When I realized I was the king of the rhyme

I got on the microphone – and what do you see?

Hah, the rest was my legacy

I was born to be the king of the be-bop swing

To have stallions and medallions, big diamond rings

I own a castle and a yacht, two million in gold

Because rap is the game that I control

I’m like Shakespeare, I’m a pioneer

Because I made rap something people wanted to hear

See, before my reign it was the same old same

‘To the ba with the ba’, that street talk game”

He made rap something people wanted to hear. How many rappers can say that about themselves, historically speaking? The premises would have been perfect for Glover to cement his legacy with a solo career. But despite separating himself from the Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five franchise and recording a couple of solo singles during the ’80s, he was never quite able to leave his old school roots behind, at one point leading his own Furious Five (which included original members Cowboy and Scorpio) as Grandmaster Melle Mel and stuck with recording sequels to his biggest moments like “The Message” and “White Lines (Don’t Do It).”

After the mid-’80s, Melle Mel was at best respected as an elder statesman of hip-hop, and at worst the ripped guy who couldn’t keep his shirt off whenever the cameras clicked. His only solo album listed on discogs.com, “Muscles” from 2007, seems to underscore the prioritization of brawn over brains as far as the image goes. But to be a critic is to look beyond the cover, and if such a rare artist expresses himself, the genre should take heed, even if it’s only in retrospective.

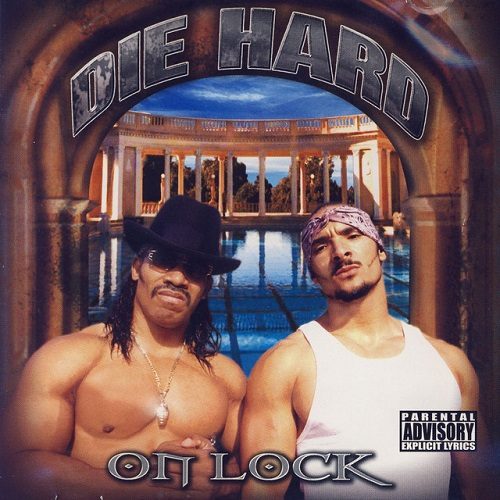

His 1997 joint album with Scorpio, “Right Now,” featured a certain Rondo on the song “On the Down Low,” and through whichever circumstances he wound up recording an album with the same Rondo in 2001. Rondo had rapped for the late San Francisco DJ/beatmaker (and one-time Too $hort collaborator) Crazy Rak aka DJ Universe between 1992 and 1994 before embarking on a solo career with 1999’s “Success Before Death” album. Given that backstory, it’s clear that “On Lock” was an exceptional clash of different generations, locations and statuses.

Yet it exclusively takes place on Rondo’s turf. Going in, the East meets West character of their convention is nonetheless stressed repeatedly. Coastal rivalry had subsided by then and the South was on the rise, and openers “You Know” and “Raise a Glass” explicitly acknowledge that. Keen on proving their chemistry, the two rappers almost overpower the music in the first tracks, trading and even finishing each other’s lines. Later on they strengthen their bond on “I Got Ya Back,” engaging in a conversation that casts Mel as Ron’s mentor. [Rondo:] “The closest thing I came to traveling was a referral.” [Melle:] “Keep f***in’ with me, though, and I’ma show yo ass the world.” On the title track, Rondo (who was 30 at the time and owner of Crucial Records) redefines his role and emerges as an entrepreneur who knows exactly what he’s doing:

“Ever met a motherf***er real as me?

Takin’ out you hoes in this industry

Suckas try to diss my bigger nigga Mel

Wouldn’t give a pioneer a record deal?

Cause you bitch-made niggas is stupid and dumb

Wouldn’t know a hit if you got knocked the fuck out by one”

When rappers fail, it’s never for lack of good intentions (or tall-talking declarations of intent). Melle Mel still had a vocally imposing presence, having noticeably updated his flow. “Pure rhyme flower, untouched by baking soda” is a rock-solid reclamation for its time. He is concerned about the legacy he once saw so clearly. The question is, however, if a claim like “Beware who you f**k with, rookie / Cause before you was born my songs taught pimps how to get pussy” isn’t more akin to ‘that street talk game’ he so efficiently denounced in 1984. At the same time he adapts to the new environment with quite a number of West Coast references. But while Rondo is able to allude to personal experiences, ‘Big Melle’ – as he is called throughout the record – is busy keeping up appearances. When Rondo seeks redemption for himself in “It’s All Good,” Melle directs (or deflects) the attention to a third person with cautionary rhymes.

Self-proclaimed “King of the Streets” way back in 1985, he becomes an accomplice in petty s**t like homophobia (“The Ghetto”) and misogyny. He sounds like a sleazy salesman when he promises his partner success on “I Got Ya Back.” “On Lock” features a part about “black hoes” that you’d expect to come from Luther Campbell’s mouth. “Don’t Stop” sees the veteran lyricist try to get steamy with lines like “G-spottin’ a hottie with a Versace body” and “You don’t want me to go there / (Baby – oh yeah).” What woman wouldn’t be attracted by the prospect of being served “quicker than fast food”? On “Bang Bang” his threats read as if he was some completely random ’90s street rapper unsuccessfully wrestling with metaphors: “Have your punk ass marinatin’ in your own body fluids.” Wait – it gets worse: “I’m waxin’ niggas like hairy bitches’ legs and surfboards.”

Even though it didn’t resonate with the greater hip-hop public, “On Lock” is a product of its time. The music switches between later 2Pac material and the commercial salvos coming from the Roc-A-Fella and Murder, Inc. camps. Rondo lapses into Shakur’s cadence several times. Practically all tracks are equipped with melodic hooks, one time recalling Butch Cassidy’s funk falsetto (“On Lock”), another the Curtis Mayfield-inspired Pharrell from the early ’00s (“Nigga What!”). With the exception of the singers, unfortunately the performances constantly come up a bit short. “You Know” hammers with the hyper-masculinity of a Westside Connection record but lacks the lyrical finesse and vocal precision. “Can’t Fuck With Us” is a “Girl’s Best Friend” knock-off capped by double-time flows cribbed from Twista. The album also falls into a time when songs were supposed to appeal to both sexes, often in the most basic manner by explicitly adressing men and women separately (an extension of the ‘Ladies say… fellas say…’ routine). While “My Niggaroes” and “Nigga What!” do so strictly along gender stereotypes, “Can’t Fuck With Us” makes sense in its battle-of-the-sexes context. It’s certainly a more sophisticated offering than the majority of the tracks here and only rivaled by “Be a Player,” a reflective song that subverts the lowered expectations by encouraging you to be a player “in this game of life.”

A wise judge will typically, before passing a verdict, remind the vengeful of how society has failed a delinquent. In this case we cannot fail to note that in 2001 Rondo made a move that puts to shame any rap profiteer indebted to a pioneer – a stigma worn by practially every hugely successful music act in history. Insofar as the hip-hop pioneers could be helped (drugs took their toll on especially the first generation), we didn’t help them enough. Ron Valentine, a man with his own cross to bear, made a difference. That’s the laudable aspect about the Die Hard project. The outcome was, well, not so successful. On the plus side, it’s an actual collaboration that never sounds like a charity project, as well as a fairly well-structured album, in its overall impression constructive rather than destructive. But it’s also a full hour that will repeatedly remind you of the 2Pac and Jay-Z catalogs without even remotely coming close to these figures. ‘Big Melle’ finds himself stranded on an ultimately stereotypical West Coast record that tries to ride the musical waves of the moment with insufficient expertise. The bicoastal character remains abstract.

From a historical perspective, “On Lock” was below Melle Mel. It does have some redeeming qualities, but its greatest quality – the presence of Grandmaster Melle Mel – is also invariably the biggest source of disappointment. Even factoring in that it was a difficult time and territory for a comeback, in the end it’s simply another chapter in the tragedy that befell hip-hop’s pioneering emcees, even in light of the fact that it’s effectively one of the better used opportunities that presented themselves to this particular legend.