Far be it from me to call one of the masters of hip-hop music’s attention to the fact that someone else may have beat him to an idea, but not that long ago fellow beatmaker and cratedigger Lord Finesse issued a series of releases billed as “The SP 1200 Project”, an homage to the drum machine/sampler composite SP 1200 from E-mu Systems (alternatively the ‘SP-1200’ from ‘E-MU Systems’, the exact nomenclature of both brands is undetermined) and the sound aesthetic for which it stands. That is, a concrete, firm sound that still has plenty of bounce (or swing, in technical terms) to it.

The symbiosis between man and machine is typically complex, and like all other musical instruments the SP 1200 offers musicians a range of possibilites, but not an unlimited one. In fact, as current or advanced as it may have been in 1987 when it was introduced as the successor to the first ‘sampling percussion at 12 bits’ gizmo, the SP-12, by today’s standards it’s an archaic hardware that is incredibly limited. But people taking advantage of the technical shortcomings of a device (or even the complete lack thereof) is essentially hip-hop, and as in the case of the most iconic drum machine, the Roland TR-808, technology determined the outcome of its use to no small degree (and subsequently hip-hop production). As the author of 2011’s ‘SP-1200. The Art and the Science’ book, PBODY, put it philosophically, ‘It’s not what the SP’ does, but rather what it doesn’t do.’

Still if we get to the bottom of its legendary status, the SP 1200 was definitely a box of tricks that could do things others couldn’t. The main property at the time was the combination of drum programming and sampling in a – relatively – affordable machine. Telling apart the machinery used in mid-to-late-’80s rap music (the formative years for sampling in hip-hop) is difficult even for experts, but what seems clear is that the specific features of the SP 1200 (and prior the SP 12) fueled the advancement of hip-hop and enabled the likes of Marley Marl, Paul C, Kurtis Mantronik, Hank Shocklee and Ced Gee (and possibly Hurby Luv Bug, Howie Tee, 45 King…) to put their sonic theories – and the original blueprint for hip-hop – into practice. With four individual memory banks adding up to 10 seconds sampling time (and the possibility to creatively work around those constraints), the ability to load and sample drum sounds externally and thus assemble an individual drum library, the option to trigger sampled sounds, it was essentially a mobile workstation that enabled you to build the bulk of a hip-hop beat (often in connection with an Akai S 950) outside of the studio system. It was then that the beatmaker was born.

After the manufacturer was bought up by Creative Labs in 1993, the SP 1200 did make a bonafide return when it was relaunched in 1997, specifically owing to its popularity in hip-hop, improving slightly on the storage media but retaining the defining 12-bit sampling rate. The impact of this first (and, to be honest, only real) return of the SP is uncertain as Akai’s MIDI/Music Production Center series had established itself as the hip-hop producer’s weapon of choice at least since the mid-’90s. Pete Rock obviously hasn’t relied on one single machine to craft his masterpieces. His use of the S 950 and the MPC 2000 XL is documented, and it goes without saying that the tracks you know and love weren’t finalized on one widget, however wicked, but passed through a couple more hands and circuits.

“Return of the SP 1200” gathers ‘beats from 1990 to 1998’, which would exactly span the time between his first production gigs such as the two tracks on the Groove B Chill album and Johnny Gill’s “Rub You The Right Way” remix and his lauded solo LP “Soul Survivor” from 1998. Detractors would define that to be pretty much the relevant part of PR’s career, but if only it was that simple. Better yet, we should be thankful that it’s not that simple.

The issue is as pressing as ever – to what extent do we strive to keep pace with technological progress? Music has been dealing with that dilemma for more than half a century, man usually finding creative ways to tap into machines. The advent of digital audio workstations challenges our notions of what ‘making music’ means. The basic argument that all music is still human creation (at least until we let artificial intelligence take over the creative industries) is only partially refuted by the fact that each hardware dictates a specific workflow and produces a specific output, because the human mind is the real ghost in the machine. Yes, the SP has been essential to renowned hip-hop producers such as DJ Muggs, Tony D, Prince Paul, Large Professor, DJ Quik, RZA, Easy Mo Bee, Q-Tip, Sir Jinx, Ski, Jay Dee, Da Beatminerz and Johnny J, but what they made out of it differs wildly.

Still, if you listen to instrumentals predominantly done on a SP 1200, you’ll likely hear the overriding qualities users invariably characterize with ‘crunchy, digitized drums, choppy segmented samples, and murky filtered basslines’, ‘a unique depth and color to its sound’ that makes ‘drums sound fuller, melodies sound wider’ (all quotes found online). I recognize my own preferences in these depictions. It’s been a long-held conviction of mine that boom bap beats in particular have a much greater risk to go awry when done mainly on an MPC than on a SP. Between gritty and glassy I’ll always take the former. But I’m also grateful that the sound of hip-hop has always evolved, both under the influence of new technology and changing tastes. Even during the period in question it was important that producers could choose from an arsenal of machines (and human musical expertise once it came to recording, engineering and mastering).

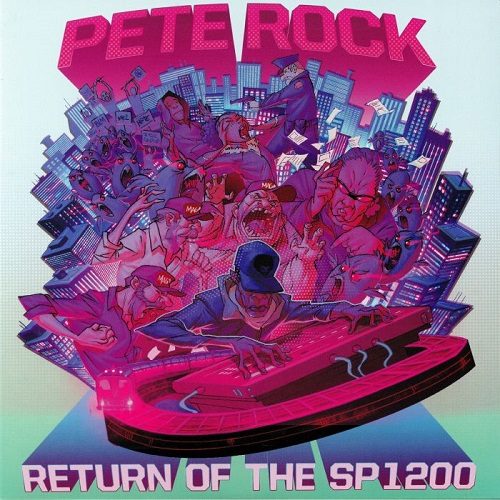

“Return of the SP 1200” is not Pete Rock’s first blast from the past, considering similar projects from “PeteStrumentals” in 2001 to “Lost Sessions” in 2017. As expected the release contains solid material from start to finish. It ticks familiar boxes with “Tru Master” quotes, Kane and Biz samples, dancehall elements, loyalty to (black) music history etc. Experts will be able to just imagine the producer manipulating the machine during each beat, all others will be at least able to discern the delicate arrangements. Listeners possessing a basic familiarity with Pete Rock’s production history can try to roughly locate the tracks in time. One period of origin of several selections should be the mid-’90s. Opener “Dreamer” is reminiscent of the subdued groove of the InI album (recorded in 1996), oozing with the organic vitality of a swamp. “Round Midnight” and “Food For Thought” are probably slightly younger, the Chocolate Boy Wonder offering peace of mind, possibly following the example set by The Ummah. “Live From the Basement (Up, Up and Away)” and “Street Dreams” have a 1994 roughness to them. “Death Becomes You (Instrumental)” is positively from 1993, the accompanying Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth track appearing on the “Menace II Society” soundtrack, plus evidence that when you give Pete a horn section to sample, he’ll work wonders. “Kool Jazz” is proof as well and with its clear sound could date from 1992.

Pete Rock (despite having early on perfected the musical interlude) doesn’t deal in nanobeats like some of his colleagues but stretches his instrumentals at least across the two-minute mark. Some of these beats therefore tend to become monotonous, especially as they are often designed as simple contraptions that are in steady motion. In that regard “Return” is not in a league with the more sophisticated “PeteStrumentals”. Rather, tracks like “Harps of Heaven” or “A Khalimba Story” are conventional instrumental hip-hop that tinker with respective samples.

Subtlety and showing off have always complemented each other in a Pete Rock beat. This bundle of 15 beats is at times almost too subtle. Variation occasionally comes from the splicing and chopping of the samples, but more frequently things are stirred up by the vocal cuts retroactively administered by DJ J Rocc. In essence, though, “Return” is vintage Pete Rock hip-hop produced on a vintage drum sampler. The SP 1200 is how hip-hop learned to nod its head, how it learned to creatively chop samples under constraints, how to embrace the gritty and grimy aesthetic that rendered it so supremely authentic. “Return of the SP 1200” doesn’t say otherwise.