What if I told you… What if I told you that in 1981 in Los Angeles there was a white LGB rap trio who actually recorded songs and performed shows? Oh, I know what some wisecracks will say: This funny talking over rhythms thing was such a hit back then that early ‘rap’ records hosted a checkered cast of characters that included comedians Mel Brooks and Rodney Dangerfield, sports superstar Carl Lewis and grappler-turned-actor Mr. T, Austrian pop prodigy Falco and German punk queen Nina Hagen, a ‘Bumble Bee’, a ‘Rapping Rat’ and a ‘Rapping Dummy’. Evidently the novelty genre produced novelty songs, or more squarely put, what was perceived as a gimmick naturally invited gimmicky interpretations.

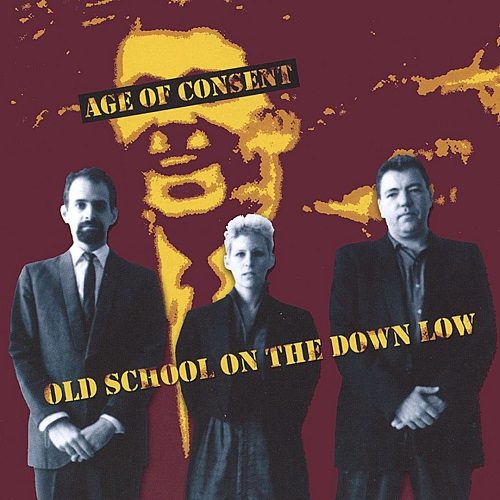

This here is different. The suspicion that Age of Consent and the group’s 2004 collection “Old School on the Down Low” could be an elaborate stunt can easily be dismissed. Testimonies, documents and even footage confirm their existence and the music itself strongly corroborates the band’s bio:

‘Music brought Age of Consent co-founders John Callahan and David Hughes together in early 1981. They met one night at a presentation given by Hughes regarding contemporary music. Callahan, recently arrived from the East Coast — a disco and rap devotee — took issue with Hughes’s dismissive criticism of disco. Callahan stuck around after the talk to exchange ideas about the music scene and to learn more about Hughes’s gay punk and performance perspective. A friendship developed. Later that spring, when Hughes was producing an experimental ‘Sound and Vision’ series at a downtown gallery, Callahan suggested a rap — a political gay rap. At the time, rap music was new enough to be considered experimental and so the two wrote “Fight Back,” an anti-gay-bashing rap, which was the show-stopper at one of the series’ performances.’

It’s not just the rap-historical context of “Fight Back” that gives us a lot to think about, but the ease and aptitude with which they go about writing and performing a rap song from a gay perspective, at a time when practically no norms existed in terms of who could do what with rap. The duo wouldn’t come back to the knee-slapping rap names they chose for their first song – Callahan was Knight of the Night, Hughes Master Bates – but the handles fit into the debate the two stage between themselves.

Callahan appears first, dropping the bombshell right at the beginning:

“From the streets of New York town

Came black rhythm rap funky sound

From the streets of L.A. town

Fag rap is spreadin’ around

You might say, ‘What’s this shit?

Rappin’ white fags just don’t fit’

We’re here to say that it’s okay

For anyone to rap – black, white, or gay”

He then seeks to establish a playboy reputation but soon invites Hughes who humorously puts a safe distance between himself and the L.A. gay scene. Banter ensues between them before they turn to the audience and conclude with the call for self-defense in the face of harrassment. The song’s set-up is evidence of a natural understanding of rap. It’s obvious that as a New Yorker Callahan is the one with the greater familiarity with the artform, but Hughes takes possession of the specific rhetoric the way many perceived outsiders since were able to find their role in rap.

There can be no doubt that what Age of Consent conceived especially in 1981 could have presented a fork in the road, at a pivotal point in rap history at that. Ignoring the sheer improbability of hip-hop music taking a direction fundamentally different from the one it did, if more people knew “Fight Back” existed, it might have at least gone down as a historical document, a reference point for inquiring minds looking what else could be done with rap. There’s a good chance that gay rap, if more people had pursued it in the 1980s, would have been relegated to the same niche existence as gospel rap, but we were never able to find out, and the active rappers that happened to have a non-normative sexual orientation decided to stay in the closet.

Learning of Age of Consent gets you thinking about how lucky the successful rappers in New York actually were to get heard on such a scale. And perhaps regret the vehemence with which others were denied the chance to get heard. In historical terms the answer to the question who rap belongs to is unambiguous. But one only has to consider the large number of early female rappers to begin to question the heterosexual male hegemony that was established in the following decades. How much diversity can rap’s self-image take? How often do historians have to refer to the roles of women and Latinos in rap and hip-hop before their contributions are accepted? It’s obvious that two white gays and a couple of chicks who played some gigs around L.A. in the early 1980s don’t constitute a revolutionary movement. Fag rap was definitely not spreading around. We don’t have to rewrite hip-hop history because of Age of Consent. But as an anecdote, or more accurately, a footnote, they are an impulse to question stereotypes, especially in light of the number of countries and cultures that have adopted rap for their own purpose.

Without wanting to praise Age of Consent as the definite role model, it’s clear that the disruptive element that rap represents (sonically and socially), the explicit language, the frank conversation, the urge for expression, would have been a good match for the LGBTQ community. That would be the unrealized legacy of Age Consent. The fact that they would have also been (or were, technically), one of the first (if not the first) persistently performing white rap group almost seems secondary.

After that first collaboration Age of Consent continued as a live project. They expanded to a trio with first Andrea Carney and then Thea Other, two women who rap as well and upgrade the group’s configuration. “History Rap” (or rather, as the recording itself suggests, “Gay History Rap”) commemorates the 1969 Stonewall revolt in New York, considered a turning point in the gay liberation movement. The female vocalist explicitly champions a female protester: “Runnin’ and hidin’ was a thing of the past / when this tough dyke started kickin’ ass”.

As remarkable as it is to report about a rap act from the early ’80s that militantly advocated gay rights, even more remarkable is the fact that the group had a lot more to offer. “Missionary Position” takes aim at televangelists, but the larger point that Age of Consent make is that straight people are just as affected when self-appointed moral authorities try to enforce restrictive sexual norms. Andrea Carney:

“Now all you women, get on your back

Give your man his time in the sack

You gotta get down and get underneath

You don’t shake your booty, just grit your teeth”

Understandably sexuality occupies several of Age of Consent’s songs. “Diddle Rap” recommends that we preserve the carefree sexual curiosity of childhood as adults, another jab at sexual repression. Yet despite good intentions, the sheer silliness of the presentation foreshadows a certain strain of comical white rap acts. This is the kind of bad start the Beastie Boys could have been off to if they were slightly older and earlier. “Performance Pressure” is literally more mature, the two men tormented by questions like “How do I rate?” and “How do I measure?” “Schizo Rap” mocks homosexuals who lead a double life, certainly a touchy subject, but ultimately evidence of how the guys claim authority on the subject, similar to their use of the f word. Carnal aspects also appear in “Twist and Shout” when AoC draw attention to the phallic shape of missiles, but it occurs in the dead serious context of the nuclear arms race of the first Reagan years. The eponymous “Age of Consent” finally is another swipe at repressive and perplexing sexual norms (“Sex was a mess, sex was death / sex was religion – or anything but sex”), the trio explaining their convictions across personal experiences.

Discovering Age of Consent was one of the most radical revelations I have experienced in my decades of rap consumption, comparable to first hearing rap in another language than English. The group’s complete works, as small as the collection may be, are a field day for rap archeologists. Is that a Spoonie G beat playing in “Schizo Rap”? Are they really rocking each a different break on “Twist and Shout”? Are we witnessing live cutting accompanying a machine drum track on “Performance Pressure”? Since the collection opens with a remix of “Fight Back”, why was the original version not included? What would an official Age of Consent album have sounded like? Would it have taken a more alternative/artsy direction along the lines of “God Sez” and “Dickie’s Dead”? What would have been Age of Consent’s reaction to Melle Mel and Duke Bootee’s “The Message”, to Run-D.M.C., to the Beastie Boys?

Fact is that Callahan and Hughes understood rap very well, beyond “Rapper’s Delight” and “Christmas Rappin'” (without having to cite Gil Scott-Heron or the Last Poets as influences). The rhymes are thought-provoking, comedic, acerbic. It sounds like rap, not beatnik poetry or political sloganeering. “Fight Back (Remix)” namechecks The Treacherous Three, for God’s sake. They understood that rap enables you to take on roles, to address issues, to make arguments and to have arguments. They understood that rap lends itself to self-reflection. Eons before Eminem, Age of Consent held a mirror up to themselves and to their audience: “Most of you are white middle class / Now we’re gonna preach to your ass”.

In fact, an intriguing detail of these recordings are the bits of laughter and cheers the song lyrics elicit from the audience. It can be practically ruled out that it was the mere novelty of such a duo or trio rapping (as rap stereotypes weren’t yet as cemented) that made people laugh but their biting approach to mainstream society and their own community. That much can be said – Age of Consent were not a joke. Their material was rehearsed, their songs had choruses, they recruited established musicians for their shows, played at the Christopher Street West festival and opened for Nona Hendryx.

To put all this in perspective, “Fight Back” predates the quintessential rap music epiphany, “The Message”, as well as Madonna’s debut album. Ice Cube was 12 years old when “Fight Back” was conceived, Beyoncé was born, Ronald Reagan just took office, Indiana Jones made his screen debut, the Columbia launched as the first Space Shuttle and it was still three years before Britsh synth-pop band Bronski Beat would release the gay anthem “Smalltown Boy” (off their debut album… “The Age of Consent”). By the time the project was abandoned for good by Callahan in 1985, Ice-T hadn’t even yet released “6 in the Mornin'”.

Beyond its legal meaning, if you think a little bit further, the term ‘age of consent’ could also describe a period of approval, of understanding. The name would then express the vision of a new era where gays and others fighting similar odds are acknowledged and accepted. As we know, despite tremendous progress on some fronts, the struggle continues. Ironically, it’s uncertain how Age of Consent would be received by today’s LGBTQ activists given the current intolerance for anything that is even remotely politically incorrect. Plus we had to learn that the whole ‘sexual liberation’ thing can kind of get out of hand. But as AoC knew already, “what’s cool in L.A. at 15 / is obscene in Abilene”. As consent remains a crucial element in any interaction between people, consent in the sense of a larger-scale consensus about how we treat each other seems as hard to reach as ever.