A new publication on the German book market that attracted considerable attention this year was ‘GRM’ by Sibylle Berg. Subtitled ‘Brainf**k’, ‘GRM’ throws up a ghastly scenario set in the near future where no one cares for anyone, except a group of adolescent outsiders who begin to take care of each other and amidst the decline of humanity initially seem to form the nucleus for a potential resistance or resurgence. More akin to a gritty reportage than a futuristic novel, all the dubious (or, well, downright disastrous) blessings that befall this planet in the present time – some of them seemingly converging with alarming concision in the United Kingdom – come together in this bestselling book – biometric recognition, surveillance society, artificial intelligence, deepfakes, industry 4.0, gentrification, micro living, basic income, privatization, reward-penalty systems, social isolation, technophilia, nationalism, mass medicamentation, child neglect, child abuse, the selling out of London to global capital, the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data scandal, the Grenfell Tower fire, the Rochdale sexual abuse ring…

Berg’s key premise is clear – it’s all happening now. We can’t escape the suffocating embrace of this brave new world who will have us figured out down to the most intimate detail. How does the eponymous music genre grime play into all this in ‘GRM’? It’s one of the few things the foursome have in common. It is part of how they deal with their helplessness and hopelessness. Their grime playlist gives them a feeling of strength and potency. The author namedrops Skepta, Ruff Sqwad, Lady Leshurr, Little Simz, Kozzie, Stefflon Don, Stormzy, Scrufizzer, Abra Cadabra and Devlin. Since the story is set in the future, the characters essentially listen to music from the past. Grime is still around, but new fictional stars are uninteresting, the genre has lost its edge, and what the group relates to are strictly older recordings, especially the vigor and anger they channel. While tunes literally play during various passages in ‘GRM’, grime is not meant to be the soundtrack to the UK falling apart (monarchy was abolished without much difficulty, instead the party who carries the election solely exists online and the prime minister is played by an actor), or the soundtrack to a not so distant dystopian global future. If anything, it seems, in ‘GRM’ the mainstreaming of grime goes hand in hand with the sedation of society.

It’s almost cliché to say that success breeds complacency. Or that the desire to succeed corrupts ideals. Grime (like its big brother rap) is not immune to such temptations, as a number of crossover attempts testify. But grime artists time after time return to their roots, to the abrasive, incisive music that originated in London in the 2000’s. One of grime’s most famed figures is Devlin, who entered the scene at a young age and after a rocky career path has come back down to the hard concrete from which grime sprang forth.

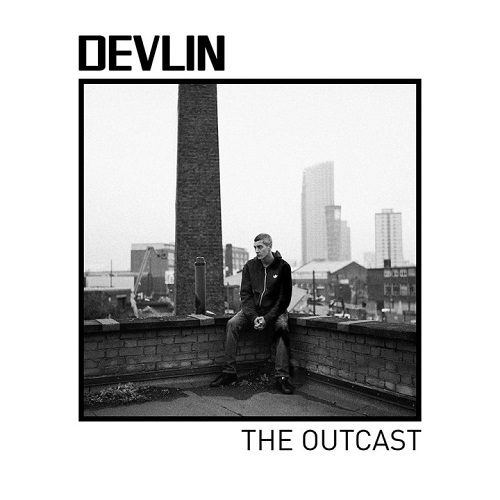

Devlin is quoted in ‘GRM’, with lyrics from “Community Outcast”, a 2006 song that also appeared on his major label debut in 2010. His 2019 album “The Outcast” then serves as a reference to his beginnings and as a reaffirmation of his special status. It’s the statement from an artist who’s back from chasing the end of the rainbow and is now simply happy practicing the craft that initially stirred his passion. Opener “Pirate” reenacts a live set on pirate radio stations such as Rinse or Deja with realistic pointers to how it was to feel the support of listeners, to find inspiration in adverse conditions like an unheated studio (“There ain’t no central heatin’ / It’s freezin’, I see my breath / It just adds to the vibe, I guess / Then I get more drive, more meanin'”). “Pirate” perfectly captures the vibe of early grime and the escape and the possibilities it offered.

And that is something Sybille Berg’s ‘GRM’ is not clear enough about – the optimistic side of grime itself. Despite its parade of combative characters, grime is a spirited event, a community of mic fiends who ‘link up’, whether to collaborate or to clash (the line between the two easily blurs). Yes, the hook to Devlin’s “Fun to Me” carries an arrogant undertone, but the message remains clear-cut. An MC like Devlin has fun doing what he does. And he’s not above letting it show and letting you know. (Go and search for current American rappers who tell you explicitly that they’re doing it for the fun of it.)

“Fun to Me” at the same time conveys the daunting side of grime, Devlin’s voice skidding across a block of ice that is incredibly hard to get a hold of. The album’s primary producer Lewi White revisits several styles of grime production, adding a pinch of garage to “Pirate”, energizing “Live in the Booth” with lashing snares and 8-bit bleeps, letting the stateside Dirty South sound inform “Grime Scene Killer”, or recreating 1980s style dystopia in “Ride 2 This”. If only to remind everyone that grime always had a sort of anything-goes tolerance that extended to pop influences, there’s that as well. Still sonically the cold, the hard and the dark prevail on “The Outcast”. But it is important to discern the sportive undertone.

A harsh spitter with a sense of tempo, Devlin is grime MC through and through. Grime tracks compress a few basic elements into near impervious slabs of sound, and the vocals and lyrics reinforce that impression as short successions of ryhmes are rhythmically arranged to operate in attack mode. Flow and rhyme schemes take precedence, the structure of the bars is as important as the content. Very often, what is said can – through form – be traced to something that was said earlier. The cadence informs the writing.

Yet there’s still content, meaning, emotions. His voice carries a sympathetic timbre, which allows him to credibly perform more emotional songs like the inspirational “Get It” or the supportive “The Light”. He displays lyrical acumen. In “Too Far Gone” he recalls “dreams of a youngster / inflated and punctured”. He creates two double entendres out of one metaphor (the “You can’t handle bars” part in “Ride 2 This”). He comes up with tattoo-ready mottos like “I know failure’s the most f**ed thing that can haunt you / But then again failure’s nothing but another spectator’s poor view”. He ironically apologizes for his silver fox appearance, quipping, “Ask why I’m grey like UK weather / Think I belong up in my grandma’s era / Old school when I show fools who’s clever”.

The “grime ambassador for Dagenham” also refers to himself jokingly as the “granddad of grime” (still a junior to the “godfather of grime”, Wiley). Referencing the years 2003/04 and the ‘crypt’ from where he first emerged with his mixtape “Tales From the Crypt”, “The Outcast” has the makings of a nostalgic album, yet is also driven by a “terrible lust to reinstate” Devlin. He may think that success passed him by unfairly (without apparent acknowledgment of personal wrongdoing), but he’s willing to face challenges and competition the way he learned to back in grime’s primordial times. To come back to ‘GRM’ the novel, in an interview its author Berg at last didn’t fail to underline that to her “grime is resistance, fun and hope”. There you go.