I recently had the opportunity to speak with Joe Rathgeber about the history of hip-hop on the internet in the 1990’s. It may or may not have been as useful as Joe had hoped, since a lot of things that were important back then were (ironically enough) not written down, and remembering things that happened three decades ago is harder than you’d think. The fact I wasn’t careful about my use of alcohol in my teens and 20’s means I may have also crashed the hard drive in my head more than a few times, so even if the data IS there it can’t be accessed. Nevertheless as we kicked the ballistics back and forth he jogged my memory of interactions on the rec.music.hip-hop newsgroup, including the fact that hip-hop artists like Blockhead, Celph Titled and Sole were all interacting with us online before they rose to underground rap prominence.

“Life is enough of a gamble for me/so I play dice with my soul every time I walk down the street/I’m looking for a sure thing/and instead I got a wife that I couldn’t marry.”

In bridging those connections we wound up talking about the anticon. label and the way they sought to push underground rap forward, yet in doing so simultaneously received a push BACK by those who viewed them as being pretentious, elitist, and too far outside the norms of hip-hop music and culture. We also discussed the irony of artists who were being authentic to their own experiences were subsequently ostracized for not copying the style and swagger of popular rappers from the day — yet if they HAD been doing that they would have been accused of “whitewashing” and inventing fake personas just to sell records. When you’re the first to try something new you often wind up in no-win situations like this where you’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t.

I don’t mean to paint the anticon. collective as martyrs with that last paragraph. Some of the criticism they received was fair, some of it wasn’t, but at their inception there was a unique amount of interaction from artist to fan and vice versa. This was long before the rise of social media tools like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram made it possible to reach out and touch people online (and hope to be touched back). The blurring of the lines between artist and fan may have unintentionally led to some of the disrespect lobbed their way — the perception that these were overly eager fans of rap music who were awkwardly trying to “get in where they fit in” whether or not hip-hop heads would get their unconventional non-traditional music.

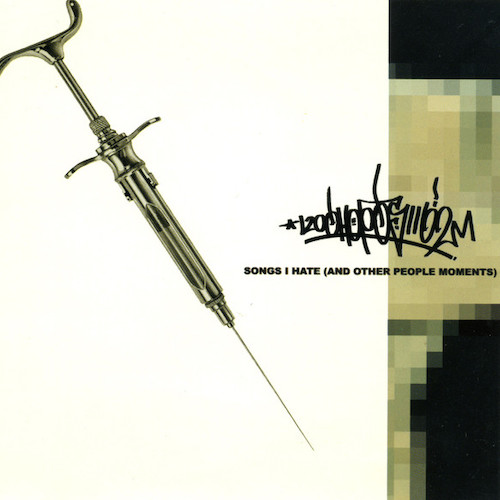

Albums like Sixtoo’s long out of print “Songs I Hate (and Other People Moments)” only helped to fuel the debate, particularly with THIRTY-FIVE MINUTE LONG SONGS like “The Canada Project Rap” featuring Adeem, Buck 65 and Sage Francis. It’s easy to pinpoint this track as the very dividing line between those who loved and hated anticon. as an imprint. A single song that’s longer than some entire albums is immediately going to bring out the wrath of the haters, especially with lines on the song like “This is the thanks I get? I never get recognized for my brilliance.” You CAN’T dodge the egotistical nature of the song nor the uncompromising words of anybody featured on it. The track is not an accident. It’s not five, ten or even twenty minutes of words that are padded out with samples and noise. It’s a legitimate half hour plus of rap and unapologetically dense ideas. “Everyone’s a cross between trees, image and God complexities.” At any moment in the song you could spend an entire hour trying to unpack it. Despite the fact this much bloat should make it corpulent, it avoids the heart attack with self-deprecating humor like “As sure as white kids perpetuate bullshit and whack rhyming.” Even if you want to hate it you wind up acknowledging a begrudging respect for what they’ve done.

At this point I have to offer you a piece of clarification that may change your mind — this was NOT originally an anticon. album. “Songs I Hate” was first released on Sixtoo’s own 6months imprint. The underground buzz for the Halifax artist got him subsequent distribution through anticon., which seemed both natural and appropriate given the “a-alikes see alike” nature of everyone involved. That said he’s not one of the eight founders of the label (R.I.P. Alias) nor can he be called a “core member.” He’s just somebody that rode the wave of their emergence and subsequent notoriety to get greater exposure, but his work in the Sebutones and as a soloist would have done that anyway… perhaps a little more slowly, but he still would’ve gotten there.

To bring this all full circle, when the writer I mentioned in the opening paragraph pressed me to name my anticon. favorites, Sole was the easy and too obvious answer. He was also an ironic one given he would ultimately renounce his one-eighth share of the label, not out of hatred or bitterness but just because he had artistically moved on from where he was as a founding member. Of course it was also fun to talk about Sole given his very public feud with El-P, giving his label both the fame and infamy that would help define it for years to come.

Sole wasn’t the only person to move on from those days. Vaughn Robert Squire retired the name Sixtoo and moved on to making house, club and electronic music as a producer. For this brief fling with anticon. though I can count “Songs I Hate (and Other People Moments)” as a highlight of the imprint. It’s every bit the things anticon. critics hated, but Sixtoo was already an unlikely rap star hailing from Halifax as it was, so not giving a fuck and making the music he wanted to was just par for the course. He fit in with them perfectly.