Once mixtapes had moved from cassettes to discs and then into digital files, the very idea of a mixtape became blurred as artists pumped out a constant stream of the things. Being known (perhaps to his detriment) as a mixtape rapper, Saigon was always an exciting emcee who combined the hyper-lyricism of a Papoose with the upfront bluntness of an Uncle Murda. These three artists almost captured that late 2000s identity of New York hip-hop as lyrics-centric, despite often leaning on age-old tropes of 90s rap from the East Coast. The inherent disadvantage of being a New York rapper breaking through in the 2000s was that, particularly if you fell victim to the radio, much of the work was inferior to what came before. Even emcees who blossomed in the 90s were unable to replicate their earlier form, so a new emcee like Saigon had to try even harder to impress. Saigon is an impressive emcee, which made the hype behind his debut album all the more understandable, and ultimately frustrating when it was frequently delayed. “The Greatest Story Never Told” eventually dropped in 2011 and it managed to deliver on the most part. Unfortunately, even a Jay-Z assist on the lead single couldn’t get Saigon over outside of hip-hop circles, but that was released FOUR years before the album dropped. After the 2007 50 Cent vs. Kanye West sales battle, New York saw a number of lyricists flirt with crossing over, but it was clear that the reign of hardcore rap on the pop charts was starting to wither. When Saigon’s debut charted at #61 on the Billboard 200, the same year J. Cole, Mac Miller, and Kendrick Lamar all debuted, it was a different landscape.

In the intervening decade, Saigon’s albums steadily declined in quality. This is primarily due to the production budget shrinking each time, something the reviews of 2012’s “GSNT 2” and 2014’s “GSNT 3” both cite. After a six-year hiatus, Saigon dropped a 7-track EP on Strange Music and then followed it up with this, technically his fourth album.

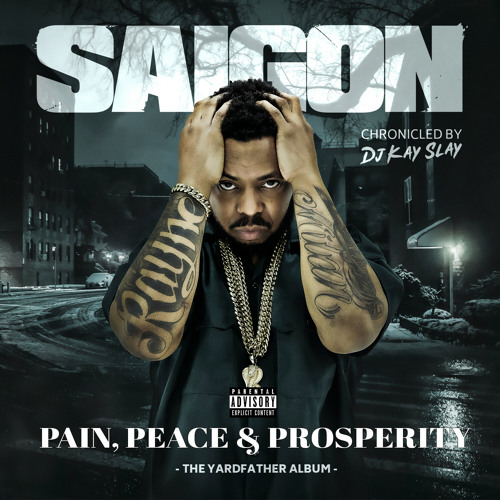

First of all, this should have been a mixtape. It might even be a mixtape, considering DJ Kay Slay’s name is on the front cover, but it’s definitely presented as an album. Production continues to be an issue, despite having Myles William on a number of tracks (he’s worked with Beyoncé) and frequent collaborator DJ Corbett dropping a few of the better beats. Myles’ delivers a sidewalk-stomper with “It Goes Up” that stands head and shoulders above the other tracks, even if the hook isn’t great. The remix to a song from Saigon’s third album: “Mechanical Animals” which features Memphis Bleek and Kool G Rap; is solid, but is certainly a cheeky inclusion.

“We Don’t Need You” boasts chanting not dissimilar to Fat Joe’s “300 Brolic” and it’s another solid Myles William production. “Pain, Peace & Prosperity” would have been a much better record if Myles’ held down the full project because his beats sound levels above the other songs. “The Co-Op Cipher” with Cassidy is EXACTLY what fans want from Saigon and while it’s not likely to set the world alight, hearing Sai go in over a heavy instrumental and add some humor in is more than welcome. However, being the last song it’s too little too late.

You see, the bulk of “Pain, Peace & Prosperity” is serviceable mixtape material, but there are some surprisingly bad songs: “2 for $5” is a dated attack on hoes that is dressed up as a concept that applies to drugs, rappers, and other derivative themes. But “The D” is legitimately one of the worst songs I’ve ever heard; two minutes of “I can’t give her love but I can give her the dick” being awkwardly sung – presumably by Saigon. It’s something you might jokingly make after a slow day in the studio, or perhaps use as a 30-second skit between songs. It’s just strange and while it’s designed to lead into “Warm Honey” it’s far too long. Speaking of which, “Warm Honey” is another odd moment, with Saigon boasting of chasing skirt through social media whilst admitting he needs a successful woman for their money. It’s the classic gold digger tale with roles reversed, with Saigon as the broke hoe flaunting his body (“the dick”) in the pursuit of money. It’s a brave, certainly admirable approach that never goes full-on balls-deep with the concept.

Social commentary perhaps isn’t Saigon’s strength, and it’s revealed on tracks like “Blessing”, which revels in the masculinity flex of having guns, just as much as it questions the damage throwing more guns at a situation incurs. This is often where Saigon lets himself down, leaning into comfortable trappings of hollow street posturing, as opposed to his talent for telling a captivating tale. It’s very much style over substance, yet the style often falls short too. There’s no Just Blaze or DJ Premier beats elevating the bars, nor guest verses from a familiar face (ie. Styles P).

“Pain, Peace and Prosperity” is Saigon’s least effective release yet; sounding markedly lower budget than previous efforts and lacks the sharpness both in wit and writing you come to expect. I really wanted to like a new Saigon album but for every forward step, there are numerous backward. It’s not necessarily a bad album and Myles William does lend some proper Saigon tracks, but it is Saigon’s worst album; a forgettable experience from an artist who has shown glimpses of being a true great.