THE LIST (CONTINUED)

11) Pet Shop Boys – “West End Girls” (1984/1986)

Enduring electro pop duo Pet Shop Boys owe a lot to their breakout song. The 1984 original produced by Bobby Orlando made its round in the clubs, but it was the re-recorded leaner 1985 version with another American producer, Stephen Hague, that catapulted the song to worldwide success. Neil Tennant‘s rap/chant sequence was present both times, but the raps were slightly shortened for the familiar version. ’80s pop had an unusual realistic streak (at least some of it and at least compared to pop music in general), and “West End Girls” has definitely such an edge with its talk of a “dead end world” (notice the rhyme with “West End girls”!) and opening couplet “Sometimes you’re better off dead / There’s a gun in your hand and it’s pointing at your head”. “West End Girls” is, according to the artist, about class distinctions and inner city pressure and drew inspiration from the T.S. Eliot poem ‘The Waste Land’, Melle Mel & Duke Bootee’s “The Message” and a gangster movie with James Cagney.

“West End Girls”, contrasting sober matter-of-fact rap vocals with melancholic singing, remains, more than three decades later, one of the finest incorporations of rap as a form of expression into pop music. And that’s with the hindisght of thousands of similar instances, many of them involving professional rappers. “West End Girls” is the historical gold standard at the intersection of pop and rap.

*

12) The Housemartins – “Rap Around the Clock” (1986)

The Housemartins had a huge hit in 1986 with the acapella “Caravan of Love”, which, although carrying a Christian undertone, neatly fit into a heap of hundreds of other sensitive yet slightly quirky hits from that period and region. It’s pretty obvious that their “Rap Around the Clock” (on some versions a b-side of another single) from the same year is a piss-take. It butts rap clichés against rock clichés in a non-too subtle manner, complete with hilariously unfunny lines like “This rap is so bad it’ll give you the rash”. Between a James Bond interpolation and other stuff there is beatboxing, which eventually gets sent up with farting noises. It’s the type of Let’s-give-it-a-try thing that should have stayed in the rehearsal room.

But it also namechecks Housemartins bassplayer Norman Cook, who pretty much around the same time presented his first publication as a serious student of rap and hip-hop on a white label, a ‘mega-mix’ collage of rap samples interspersed with a self-programmed rhythm track. On one version, Norman Cook exchanges rhymes with Wildski, mentioning both the Beastie Boys and the Clash, possibly as an example for the musical unity they attempt to describe shortly after: “The Bronx / where the punks and the b-boys sing the same songs”. Which is, especially in view of “Rap Around the Clock”, a clear indication why Norman Cook wold go from plucking bass guitar strings in Hull to pulling the strings behind massively successful electronic dance projects such as Beats International, Freak Power and finally Fatboy Slim.

*

13) T’Pau – “Heart and Soul” (1987)

’80s pop groups are often associated with that one hit that most members of the audience who have no additional interest in the act remember them for. For T’Pau, that would be “China in Your Hand”, right? Turns out, the Americans took to “Heart and Soul” from the same year. Allegedly after it was featured in a Pepe Jeans commercial… The rap parts occurred by chance when singer Carol Decker, looking to compliment a sequencer-generated bass riff, came up with “these syncopated sort of nonsense noises” and producer Andy Piercy suggested she turn them into a rap.

Two things surprise about “Heart and Soul” – that the rapping doesn’t just take up the intro but makes up the bulk of the track and that the sung and the rapped vocals overdub each other. It’s sort of a prototype of pop and rap stimulating each other to create some trademark ’80s coolness. I wouldn’t be surprised if the song would have been used in one of those topical montages in ‘Baywatch’ (a romantic reflection on a past relationship, perhaps). Almost as if wanting to extract the remaining musical sentimentality, T’Pau also engineered a “Heart and Soul (Beats and Rap)” version that excludes any pop melody.

*

14) ABC featuring Contessa Lady V – “The Night You Murdered Love (The Reply)” (1987)

Musicians and the recording industry early on recognized the possibilities of rap as a conceptual tool that could be used in the context of a song. For instance, rap can bring to the stage reasoning, storytelling, poetic language, complex rhyme patterns, etc. This was evident from rapped tracks such as Jimmy Spicer’s “Adventures of Super Rhymes”, Kurtis Blow’s “The Breaks” and too many Christmas raps and answer records to mention.

The rap version of “The Night You Murdered Love”, subtitled “The Reply”, applies these findings in an environment that couldn’t be more British and more pop. Like other bands on this list, ABC shrouded themselves in layers of stylishness, and “The Reply”, which belongs exclusively to guest rapper Contessa Lady V, goes for a maximum contrast. She confronts singer Martin Fry and counters his accusations directly with wit and venom. Assuming the role of the accused woman, she responds, “Let me state my case, I’m here to clear my name / Contessa Lady V ain’t the lady you should blame”. She turns the tables, alluding that it was him who ruined the relationship. There’s an odd battle rap segment about his ‘rhymes’ and ‘beats’, but otherwise her raps are quite effective at cutting through the ABC façade: “Too formal, too normal, for a girl that’s fly as me / You shoulda been on Wall Street, baby, instead of chasin’ Lady V”. (Someone also supplies her with slicing “Funky Drummer” stabs while she’s at it, could it be the original track’s co-producer Bernard Edwards of Chic?). She mocks his statements like in a real relationship dispute and cautions, “Homegirls beware of this pop pretender”. Speaking of ‘conceptual’, the maxi single contained the original song without the rap, “The Reply” without singing, and finally, lasting more than 8 minutes, “The Whole Story”, which combined the two.

ABC went as far as crediting Contessa Lady V on the front cover of the twelve-inch, but where she came from and went to remains a mystery. What can be excluded for chronological reasons is the connection that the database Discogs.com makes to Countess Vaughn, an American singer and actress who released an R&B album in ’92 and would later successfully star in the sitcom ‘Moesha’.

*

15) Sinitta – “Toy Boy (Extended Rap Version)” (1987)

You can’t browse pop in Britain in the ’80s without bumping into Stock Aitken Waterman, a production and songwriting trio that pasted its functional soul pop and cheerful dance pop onto countless singles and albums. Their stars had a next-door appeal that set them apart from practically all pop music trends of the decade. Some ended up proverbial one-hit wonders, very few, like Australian Kylie Minogue, are known for music they made outside of the SAW hit factory. To some, Stock Aitken Waterman were the incarnation of everything that is wrong with pop music, but the following decade admittedly made even the most flagrant factory-line ’80s pop sound classy in comparison. Industry mavericks to a certain degree, Stock Aitken Waterman certainly had the expertise and weren’t dispespectful towards the heritage of their profession. And they had the hits to prove it. Nobody with the slightest understanding for pop music would dismiss Bananarama’s “Venus”, Mel & Kim’s “Respectable” or this, right? Rap however didn’t become part of their formula for success.

They duped their detractors once with a white label called “Roadblock” (’91), which, without their name associated to it, was a well received update of the prized rare groove sound. There they employed established UK rapper Einstein for one of its remixes. (The same year, another familiar face in UK hip-hop, Jazzi P, was on a SAW-produced Kylie single.) “Roadblock” was a forecast of Mark Ronson‘s retro angle but remained a singular event. The fact remains that the uber-prolific Stock Aitken Waterman used rap very sparingly, even the “Extended Rap Version” of Sinitta‘s “Toy Boy” (which also was used in the video) merely features rapping in the intro.

*

16) Morgan/McVey featuring Neneh Cherry – “Looking Good Diving With the Wild Bunch” (1987)

There’s layers to this one. Those familiar with ’80s pop will without difficulty recognize the blueprint to Neneh Cherry‘s breakout hit “Buffalo Stance” in “Looking Good Diving With the Wild Bunch”. “Looking Good Diving” was a single by duo Morgan/McVey produced by Stock Aitken Waterman. The remix at hand was done by The Wild Bunch, the Bristol hip-hop collective that would soon transform into world famous trip-hop pioneers Massive Attack. The material then went through the hands of Tim Simenon (whose project Bomb the Bass contributed to the soundtrack of 1987 with the acid house-meets-hip-hop sampling extravaganza “Beat Dis”), who brought it into its definite form, a beacon of global urban pop that marked the definitive arrival of hip-hop on that very stage – “Buffalo Stance”.

Was the detour necessary? Well, yes. Just imagine if “Buffalo Stance” never got any further than this easily overlooked b-side experiment, a colorful pastiche that comes across like a postmodern – meaning more modern – cousin of ABC’s version of “The Night You Murdered Love” with a virtually anonymous female guest MC. That was not to be Neneh Cherry’s role. (Not to mention her husband Cameron McVey’s role as executive producer for Massive Attack’s “Blue Lines”.)

*

17) Samantha Fox – “Naughty Girls (Need Love Too)” (1988)

In the ’80s every straight teen boy with access to a tabloid newspaper knew Sam Fox. In retrospect it’s hard to wrap your head around the fact that a 16-year old could pose topless and soon become the most famous pin-up of the modern era, but where there’s puritanism there’s always plenty of room for the opposite, in this case the long accepted Page 3 girls. Ms Fox also tickled the aforementioned boys’ fancy with the lascivious hit single “Touch Me (I Want Your Body)” in ’86. Her singing career actually started three years earlier, parallel to her modeling career, with “Rockin’ With My Radio” (as S.F.X.), but it wasn’t until she became a fixture in the tabloids and weekly magazines that she got her (small) role in ’80s Brit pop.

While it would be inconceivable that she would have embraced rap to the extent the Spice Girls did a decade later, she did drop a few lines on the occasion of teaming up with American production powerhouse Full Force in ’88. “Naughty Girls (Need Love Too)”, which rose to #3 on the Billboard Hot 100, sees her exchanging brief banter with the crew (including a reference to their “Alice, I Want You Just For Me!”), and while she never breaks into more than a few bars, rap marks its presence a few times here (without leaning too hard into an American accent).

*

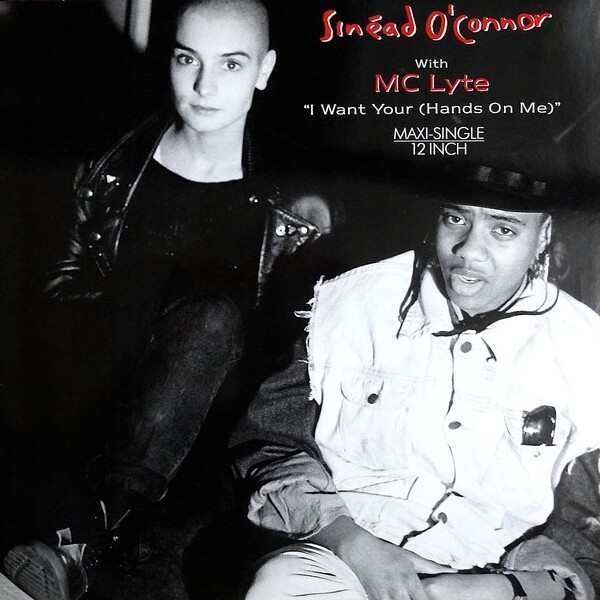

18) Sinéad O’Connor featuring MC Lyte – “I Want Your (Hands on Me)” (1988)

Earlier this year, we compiled over 200 North-American guest raps on European releases in the ’90s. This one here is the grandmother of them all. And not only that, it also covers the ‘remix w/rap’ format that really took off in the following decade.

Sinéad O’Connor fascinates until this very day, as she can look back on a lifetime (she published her autobiography ‘Rememberings’ this year) of overcoming two very personal moments the entire world was witness to, one being “Nothing Compares 2 U”. It is often forgotten that she already called attention to herself with her 1987 debut “The Lion and the Cobra”. The next year, Ensign Records put out this single and put Brooklyn’s MC Lyte into the mix, at the time likely only familiar to rap fanatics. Still she shares the single’s cover with O’Connor, which is extremely rare for duets of this kind.

Lyte is introduced via scratched in vocals from her own “I Cram to Understand U (Sam)”. Her part begins strong with “I’m not the type of girl to put on a show / Cause when I say ‘no’, yo, I mean no” before she surrenders to the object of attraction. Lyte’s rap lacks a climax, but as short as it is, it still communicates the no-nonsense character of hardcore rap in its heydays. The beat remains practically unchanged in regards to the album version, so that with or without Lyte “I Want Your (Hands on Me)” is a fairly standard example of the mélange of dance and indie music (also known as alternative dance) that also carried well in the ’90s.

Much less standard was another feature by an American female vocalist O’Connor invited to a remix that year, obscenities-flinging performance artist Karen Finley on “Jump in the River”. Although rap would soon produce its share of women offensively claiming sexual autonomy.

*

19) Mint Juleps – “Girl to the Power of 6” (1987)

What I previously said about Samantha Fox, that she wouldn’t rap extensively in Spice Girls “Wannabe” fashion, is exactly what vocal group Mint Juleps did (a year before Fox’ Full Force asssist) on “Girl to the Power of 6” (sounds like a song title Prince came up with for Vanity 6). Otherwise known for acapella harmonizing, they used this single to take their act to the present and reconnect with their urban background (four of them were sisters, all hailed from the East End).

*

20 a) Lisa M – “Going Back to My Roots” (1989)

20 b) Eighth Wonder – “Baby Baby” (1988)

The reason these two songs both make up the final entry in this list is not that both their singing and rapping ladies have a child with Oasis’ Liam Gallagher. (Really not. Well, maybe just a little bit.)

It’s to illustrate that in the late ’80s it had become an option for white and black European female pop singers to bust a rhyme, something their American colleagues were probably more prone to at the start of the decade. Rap really had become a tool of pop expression – although looming on the horizon was already the imperative of rap as black, male and urban American. Produced by The Style Council’s Talbot and Weller (see Part 1), “Going Back to My Roots” was Lisa M‘s second single after she signed with Jive at age 17. Despite her youth, she must have already known how it feels to lose touch with one’s origins, at least that’s what her – formally fairly generic – ode to her (south London) roots suggests.

Patsy Kensit, involved with the film industry since a child actress, landed a few notable roles as an adult in ‘Absolute Beginners’, ‘Lethal Weapon 2’ and ‘Twenty-One’. But she also fronted the band Eighth Wonder between 1983 and 1989. They had bigger hits (like the Pet Shop Boys-penned “I’m Not Scared”), but “Baby Baby” is our choice as the single with the rap part, production provided by Stock Aitken Waterman‘s trusted studio hand Pete Hammond.

THE POSTSCRIPT

For a brief period, rap as a vocal style and form of expression was part of the pop music avantgarde. It joined post-punk, dub and new wave for studio sessions, dance events and club gigs. Then the experimentation came to a halt sometime in the first half of the ’80s. MCing, the act of guiding party people through a night of dancing, continued in venues from Bristol to Ibiza, in nightclubs, sound systems, warehouses – but rap as a new tool in the record industry’s repertoire lay largely dormant until it was rediscovered – in Europe – as a booster for dance tracks towards the end of the decade. (Which coincided with a brief wave of British pop rap – which is not the same as rap being used in pop.)

Excluded from our 21-track list is, as mentioned before, stuff where the use of a ‘rap’ was more natural or logical. The extensive boogie rappin’ of Bo Kool‘s “(Money) No Love” (’80), funk jams like Funkapolitain‘s “As Time Goes By” (’81) and Modern Romance‘s “Queen of the Rapping Scene” and “Can You Move” (’81), or novelty tunes such as The Evasions‘ “Wikka Wrap” (’81) and Bruce & Bongo‘s “Geil” (’86). Killing Joke also featured rapper JC-001 in ’88, just not for a clean-cut rap feature (“Stay One Jump Ahead”) – but to get super nerdy, it might be him on pop duo Dollar‘s “Platinum Rap” (’86). Other occurrences are just too insubstantial, see Maximum Joy‘s “Stretch (Discomix/Rap)” (’81) or Thompson Twins‘ “Love on Your Side (Rap Boy Rap)”. And didn’t the Happy Mondays have ‘rapping’ somewhere on a record? Yes, there was “Little Matchstick Owen’s Rap” (’87), but it’s another instance of studio horseplay that has nothing to contribute to this conversation. Synth-pop normie Howard Jones also rapped on “Bounce Right Back” (’84), a sort of karma fable. But we’ll stop here.

Rap spotting, particularly when it involves going down obscure paths, is not prone to give you a false sense of security. Because you always know that there must be more out there. Raps appearing in ’80s pop can hide on the unlikeliest records. That’s kind of the point. Ask any veteran crate-digger.

Or they did occur on relatively famous records but still go undetected if you’re not intimately familiar with the respective discographies. Have David Bowie, Peter Gabriel, Simply Red, The Police or Duran Duran not once used rap or something similar between 1980 and 1989? I’m not sure.

What is clear is that Britain was the main gateway to the rest of Europe and the rest of the world for rap and hip-hop in the 1980s. The connections there were simply stronger than elsewhere. Some of which we unraveled here, while others may be even more sturdy but don’t fall into the pop/rap overlap (think Adrian Sherwood and his many collaborations with former members of the Sugar Hill house band).

Our two volumes of Early Sightings of Rap in 1980s Pop – United Kingdom are roughly split between two fractions – punk/new wave and synth-pop/dance pop. The former’s use of rap is more experimental, the latter’s more functional. Safe for that ABC tune, none of the writers, producers and performers were overthinking the use of rap, for better or for worse. To the point where some of it might get labelled as appropriation nowadays. As a Red Bull Music Academy article puts it cheekily, ‘If an archaeologist were to examine the UK charts between 1980 and 1983, they might surmise that rap was a white innovation’. That of course was not the intention. British rock and pop musicians are traditionally keenly aware of the foundations of their genres. That didn’t prevent the artists presented here from using “that rappin’ thing” (as Adam Ant referred to it) with a refreshing, joyful naivete.