To this day – some 40 years after hip-hop was first recorded for commercial purposes – the smiling rap star is the exception to the rule. The cliché is very much true that no self-respecting rapper post Run-D.M.C. would have cracked a smile, not officially. No professional photographer with experience in the industry would have told a rapper to smile for the camera when posing for press pictures. That stance was reinforced during rap music’s militant and criminal phases, and well into the current century the black smile remains suspect in hip-hop circles, just consider the members of the group Little Brother sarcastically putting on happy faces on the cover of their album “The Minstrel Show” in 2005.

That’s why gold fronts and even more extravagant grills, at least during the period when they became inescapable, were an irritating contraption for purists. At least showing off dental jewelry typically results in a defiant grin, one of those variants of smile and laughter not solely signaling inoffensiveness and innocence. Even back in the day (the ’80s) Just-Ice’s booming voice escaped through gold fangs, Slick Rick conveyed superiority through his golden smile and Flavor Flav’s grill-adorned grimace contrasted Chuck D’s angrily pursed lips.

It goes without saying that cracking a smile makes you no less of a rapper. The likes of Kurtis Blow and Heavy D were both cordial rap personas and formidable rap artists. Media personalities have usually no problem breaking through a rapper’s reserve in less formal settings such as radio appearances, etc. Two greats who felt obliged to shoulder the weight of the world, Scarface and Tupac Shakur, recorded a touching duet called “Smile” months before the latter’s violent death. And generations of rappers could literally laugh all the way to the bank.

But the (friendly) smile is just not an integral part of rap’s physiognomy. Even natural born optimist Common eventually came out with an album called “Nobody’s Smiling” (a nod to the notoriously stone-faced Rakim and his song “In the Ghetto”). And superstar Drake is as much known for his pensive poses as for his broad grin. Xzibit couldn’t have wiped the smile off his face even if he wanted to as a host of ‘Pimp My Ride’ but his music was still spoiling for a fight.

Nevertheless, and hip-hop was all the better for it, it also has always attracted people who simply choose to be their buoyant, good-humored self, among them prominent personalities like Chance The Rapper and Andre 3000. There was a time, actually not that long after Run-D.M.C., when rap artists such as Doug E. Fresh, Salt-N-Pepa, Kid ‘N Play, DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince decided to greet the world with a smile. They were not the sole reason teenybopper tabloids with a focus on commercial hip-hop such as Word Up!, Right On!, Rappin’ or Fresh existed, but their friendly faces certainly helped defuse some of rap music’s perceived menace.

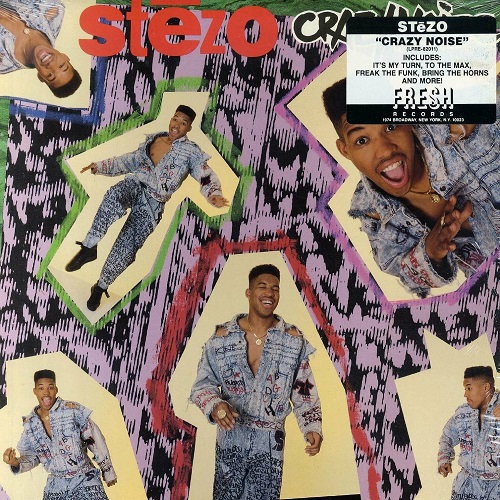

Stezo would have smoothly blended in. Alas, he did not rise to that level of prominence. Nonetheless his career was quite eventful, short as it was. Residing in New Haven’s Brookside projects, Steven ‘Stezo’ Williams was a young fanatic who took part in all the manifestations of hip-hop, from deejaying to rapping. But his strong point was dancing. He had a competitive character, winning local contests as a dancer and also making trips to New York’s Latin Quarter, at the time the epicenter of the hip-hop evolution of the late 1980s, looking to compete with the best. When budding rap duo EPMD, whose PMD still attended Southern Connecticut State University – within view of Stezo’s stomping grounds – performed at a local New Haven club, Stezo went in there with his partner Divine from Brooklyn and literally drove EPMD’s dancers out of their jobs.

Now officially a dancer for EPMD, in 1988 he made an acclaimed appearance in their video for “You Gots to Chill” (alongside fellow dancer LG 56), where he vowed specators with his dance The Steve Martin in a self-tailored yellow velours suit. He immediately went on the Run-D.M.C.-helmed Run’s House tour with EPMD and by the time the Long Island duo had its debut album together, Stezo was pictured in the group photo on the back cover of “Strictly Business”. As legend has it, Stezo knew how to draw attention to himself, possibly arousing envy in some performers he shared the stage with (including MC Hammer). After getting into at least one quarrel, he was sent home by PMD.

Back home, he invested what he had earned in a three-song demo with the help of Dooley-O and Chris Lowe and EPMD engineer Charlie Marotta, shopped it to Virgil Simms, head of Sleeping Bag Records, and that was the start of his solo career. Despite Sleeping Bag being the home of EPMD (via subsidiary Fresh Records), Parish Smith and Steven Williams would not reconcile, especially after the latter heard from Simms that EPMD had offered the label $50’000 for not signing him. True or not, this anecdote serves as an indication of the threat that Stezo’s talent seemed to pose to rivals.

Stezo’s debut single “To the Max” b/w “It’s My Turn” was played by both New York hip-hop radio giants Red Alert and Marley Marl, each favoring one side. The one that made history was the latter because it was the first rap song to sample a drumbreak from the Skull Snaps recording “It’s a New Day” that would become one of the defining rhythm tracks of 1990s hip-hop.

While Stezo’s immediate colleagues from that time credit him with getting the hang of sampling (on a Casio SK-1) more easily than they did, it’s established that his cousin Dooley-O initially discovered the break and used it for a song he named “Watch My Moves”. Having also unsuccessfully pitched what became the Stezo song “Crazy Noise” to Sleeping Bag, Dooley let Stezo have the “It’s a New Day” break, and that gesture eventually brought forth “It’s My Turn”. According to Dooley, “Chris Lowe produced most of the album”, while the involvement of hip-hop production/engineering whiz kid Paul C is certified (and mentioned in song lyrics) and that of hip-house artist Doug Lazy (under the alias Vicious V) is slightly confusing.

Despite the beats being built from several samples, they are often sctructured in a simple way that matches Stezo’s approach to writing and performing. Nevertheless the rapper manifests his masterplan right in the first verse:

“Hold it –

I take a beat and like fold it

Put the lyrics together and then mold it

all together, it adds up to dopeness

So I’m just hopin’ you can cope with

another sample of dope known as a masterpiece

I lay it on the table and start to feast

Mmmh (mmmh), start eatin’ it up

While my DJ Chris starts beatin’ it up

As the beat goes on and on (on, on…)

And the distance: long

Nothing but the bass just hittin’ ya

And the style of music is fittin’ ya

Stezo, the one who conducted it

Down in the basement I constructed”

The song that begins like this, “Bring the Horns”, isn’t the most evident choice to open the album as it’s rather restrained. It wouldn’t have been out of place on Ultramagnetic’s “Critical Beatdown” and the titular horns are certainly not your typical horns as far as hip-hop samples go. The following “Freak the Funk” is much catchier with a rhythm track bucking like a rodeo ride, leaving no doubt that one of Stezo’s specialities was to to lead listeners to the dancefloor.

“Talking Sense” did so with the help of the Average White Band and the JB’s. The sampling staples continue to pour in as “It’s My Turn” has space for several others besides “It’s a New Day”. Hip-Hoppers from that era would often develop close relationships with loops and breaks, and there’s a good chance that some of those relationships started on this sampling crate of a record. Extractions from funk records might have also ensured that the West Coast and the Midwest were on board, as was the case with EPMD. Speaking of, Stezo clearly patterned his delivery after Erick Sermon in particular on his breakout song but in general displayed an intuitive understanding of rapping. He had a confident vocal tone and didn’t rush his raps. Vocally he had the air of a fighter about him, sober and ready to strike. On top, he had the talent to make it look like everything went down exactly the way it was supposed to.

Perhaps sensing that he had yet to prove himself to the world outside of dancing, he didn’t hesitate to share his learning process:

“Once upon a time I had a trade

Thinkin’ of a masterplan to get paid

I got a paper, and pencil

Thinkin’ of rhymes’s like mental

I went on and on, it wouldn’t stop

Then I got the hang of it, it was hip-hop

I started rowin’ and flowin’ with the tempo

Sat and I thought: Yo, it’s all simple

I just wrote and wrote, and wrote a portion

Put it on track, yo, it was scorchin'”

He mentions his transition from dancer to rapper several times, as if wanting to suggest that if there’s one rapper who can make you dance, it should be him. The relevation that “the newest rapper, a new artist” has arrived doesn’t carry that much substance by itself, but it lends Stezo a profile. He essentially echoes the levity of youth when he alleges how easy everything comes to him. The end of the first verse of “Put Your Body Into It” is representative of the conclusions Stezo likes to draw: “Keep the crowd uptempo / It’s tracks and beats, it’s simple / Yo, it ain’t nothin’ to it / So put your body into it”. If Special Ed represents the intellectual approach of youthful late ’80s rapping, Stezo is on the spontaneous, not-thinking-twice-about-it side. Ultimately, with “Stezo-E is just a kid gettin’ busy” the artist puts it best himself, even if he does so on a track where his laidback stance leans a bit too much to the lethargic side.

For such a foundational record, “Crazy Noise” sometimes doesn’t sound potent enough. What it comes down to is that it is probably too basic and too clean to compare to the real classics. Also, topic-wise there’s not much variety, and the only song that tries something else, “Girl Trouble”, isn’t exactly laudable. “Crazy Noise” is also famous for a couple of funny mispronounciations, but that is certainly not a negative. But it could definitely do with some more lyrical gems in the vein of “Hypin’ up the crowd just like a coke sniff / Towin’ MC’s away just like a boat lift”…

The highly recommended 2020 documentary ‘The Untold Story of Stezo’ tells the story of a truly resourceful hip-hop kid, lending credence to the at first sight not fully substantiated claim to be “the inventor” found on his debut. For the record, it is said that he wrote and produced EPMD’s “The Steve Martin” himself, which doesn’t sound that far fetched (he wrote raps to his dances before) once you’ve gotten to know Stezo a little bit closer.

When Steven Williams died on April 29th 2020, those who knew him as an artist and as a private person remembered him fondly. On Juan Castillo’s show on WYBC-FM DJ Superman J of the Skinny Boys recalled: “Steve was an infectious person, you couldn’t have nothing but love for him, because I don’t know a time, that I know of, that I’ve seen Steve without a smile. He always has something to laugh at. He always has something he feels good about”.

The next time you struggle to make a connection between rap music and the pure, natural expression of joy like smiling and laughing, try to think of Stezo and the joy he brought to hip-hop – notably without looking like a clown.