I think the readers have probably ascertained by now I have a fondness for the crossover between reggae and rap that gained momentum in the 1980’s and peaked in the 1990’s. Collaborations have never gone away and you can still find rap reggae music to this day, but there was a feeling the two genres were brothers in arms that’s no longer there. The feeling in the air was that reggae artists providing hooks to rap hits was routine, and hip-hop emcees showing up on reggae albums and remixes was the norm.

Perhaps these crossovers became so commonplace that it stopped being special to the listeners, but my perception is that each genre became more insular and focused on their own audience. It probably doesn’t help that as rap had its own subdivisions between East and West, gangster and edutainment, Dirty South and DIY, reggae had roots, slackness, dancehall and so on. Some artists like Barrington Levy can transcend the categories, while others may openly disdain their contemporaries AND rap music, so collaborations are moot.

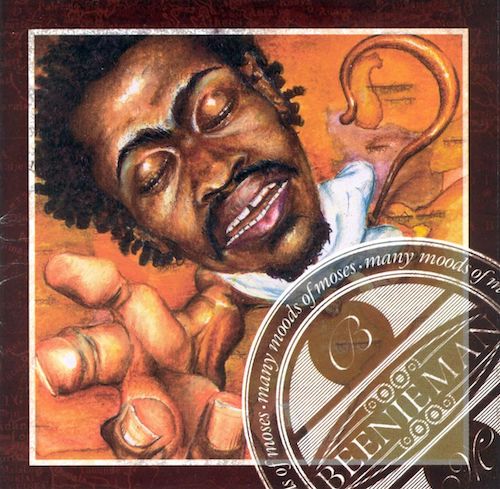

Perhaps nothing defines rap reggae crossover quite like Beenie Man’s “Who Am I (Sim Simma)” from “Many Moods of Moses.” Beenie openly references Missy Elliott’s rap hit “The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)” with his hook, but instead of asking “Beep beep, who got the keys to the Jeep?” he wants to know “Sim simma, who got the keys to my Beemer?” I’m trying not to look back with tinted shades too hard, but this just felt so natural and normal at the time, just like seeing this video on Rap City next to hers would not have been out of place. Rappers turned around and referenced Beenie Man right back, from Redman’s “I’ll Be Dat” to Nelly’s “Country Grammar” and Petey Pablo’s “Raise Up.” Like I said, this was just the norm back then. I miss that exchange between parts of the African musical diaspora and won’t pretend otherwise.

Beenie Man was also well enough established by this point in his career that songs like “Women a Sample” featuring Buju Banton were a meeting of stars, not one bigger reggae artist blessing the other with a cameo or vice versa. The same can be said of his duet with pioneering female toaster Lady Saw on “So Hot” and performing with his older brother Little Kirk on “Have You Ever.” One could perhaps argue that Beenie Man eclipsed his brother’s fame at this point, but there’s no disrespect or ill will either way on the song. It’s all love between the brethren, and now that I think about it that’s the other thing I miss about rap reggae — the feeling of camaraderie between artists who knew they had common musical roots.

If you’re looking for songs featuring American rappers on “Many Moods of Moses” though you’re going to wind up disappointed. There’s no Super Cat “Dolly My Baby” featuring Biggie Smalls, no Capleton “Wings of the Morning” featuring Method Man, no Shabba Ranks “What’cha Gonna Do?” with Queen Latifah. I’ve talked a lot about how common the crossovers and references were in the 1980’s and 90’s, but what’s uncommon here is how much Beenie Man is focusing on doing reggae and just counting on the rap audience to court him, without him having to make any overt gestures. As such the more traditional roots style reggae songs like “Got to Be There” may be just too spiritual, too “rasta” for some rap heads, but I love it.

And given that one of the most influential movies I saw in my youth was “Cry Freedom,” a dramatization of the life story of Steve Biko, Beenie Man’s tribute to the anti-apartheid activist was right up my alley (and still is).

I suppose in the traditional sense “Many Moods of Moses” might not seem to fit a site called “Rap Reviews,” but this isn’t the first time we’ve covered a Beenie Man album and won’t be the last. While there are some things that I wish rap and reggae didn’t have in common (like a healthy case of homophobia, something Beenie Man has been widely criticized for), there’s more good than bad to exploring the two genres and the spaces where they overlap. There’s not a whole lot of overlap on this particular Beenie Man album other than “Who Am I?” but Bob Marley and Shabba Ranks were my gateway drug to reggae long before 1997, so this album was right on time.