Sometimes we forget how much racism is part of the grid within which hip-hop music takes place. Without racism, hip-hop might not exist at all, or at least it would have manifested itself very differently throughout time. Racism is at the same time not some rhetoric commodity that explains everything, nor is it easy to define and understand. Quite the contrary, racism is an extraordinarily complex phenomenon. From time to time, rap songwriting tackles these complications, explicitly addressing this rather heavy part of its heritage.

While many rap songs, famous and overlooked ones, could be the subject of an advanced course on ‘racism as addressed by rappers’, this post presents the point of departure, the initial objection against racism and the violence, the discrimination, the inequalities it attempts to justify. It features artists joining forces and standing united against racism. Stating the obvious that sadly isn’t so obvious to some.

Rappers Against Racism – The List

1) “Erase Racism” – Kool G Rap & DJ Polo f/ Big Daddy Kane, Biz Markie (USA 1990)

Two of the greatest MC’s of their (and possibly all) time plead for civilized coexistence, notably under the impression of the 1989 murder of Yusef Hawkins and the ensuing racial tensions in New York City. Big Daddy Kane puts all his authority as a writer and performer into it, embodying Black pride – as interpreted by a rap artist – like few before or after him. Without a doubt this is one of his greatest performances. What’s more, “I know what’s been amended – and intended” rings loud 30 years later when the United States Constitution and its amendments are scrutinized from every angle.

For someone mainly associated with mafioso tales, Kool G Rap acts more out of character, but you may also take his verse here as the words of Nathaniel Wilson, the person behind the role: “Siberian’s no better than Nigerian / I bring a rattle to a battle that you send me in / I’m no villian, so why would I be killin’ Indians? / My nationality’s reality”.

Biz Markie finally is the actual master of ceremony, opting for a conciliatory tone that suits his natural disposition as he mentions the release of Nelson Mandela from prison and breaks into a nursery rhyme hook. At a time when we’re learning to detect racism in all its appearances, wishing it away may seem downright naive. But wishing is not the same as arguing, and that’s what Biz, Kane and Kool G are about here.

*

2) “Rap Contra El Racismo” – various (Spain 2011)

A collaboration between Spanish NGO Movimiento contra la Intolerancia and established rap groups and soloists, “Rap Contra El Racismo” was the vehicle for a school and youth campaign in ‘the language of young people to reach young people’. What it lacks in diversity, “Rap Contra El Racismo” makes up for in name recognition, featuring heavyweights of Spanish hip-hop such as Kase O, Nach and Zatu. But the laurels belong to initiator El Chojin, who leads the lineup and became the ambassador for corresponding songs across Latin America – Colombia, Peru, Mexico, Argentina, Honduras, Ecuador and Costa Rica.

In a conversation with Movimiento contra la Intolerancia a few years ago, El Chojin was pessimistic about the social and political prospects: “Now we are back to normal. Fascism has always existed and has been the form of government in most societies: the exaltation of fictitious common values, the us-against-them, the lack of empathy towards the other, imposition of moral values. (…) The perception about racism has also changed. It used to be an insult to be racist, now it’s an option. Now you can have friends who are racist. That’s the worst thing that can happen to the fight against racism.”

On his artform and activism he said: “I am the example that rap changes things and I have seen it with my eyes in hundreds of thousands of people. In Spain, we live comfortably; we have problems, but we are from the first world. In a favela in Brazil there is the Casa do Hip-Hop, and it helps many kids avoid falling into drugs. I have seen how in Guinea they use rap to bring out the kids’ inner selves, and in Palestine the same thing. There they use it as something cathartic. (…) Rap is much more important than intellectuals think. It’s not some guy in a cap talking nonsense. Without rap a lot of people would have been left without a voice, we would have been left without knowing what a lot of people think.”

*

3) “Ndodemnyama (Free South Africa)” – Hip-Hop Against Apartheid (USA 1990)

According to Steven Van Zandt, who organized Artists United Against Apartheid in 1985, music industry execs were sceptical of putting rap artists next to luminaries like Miles Davis, Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen. Ashbury Park Press quotes Van Zandt as saying, “(Hip-hop) was a very, very, very controversial thing at the time – rappers were not respected. The industry was ignoring them and hoping they would go away.”

The project’s lead single, “Sun City” saw Run-D.M.C., Melle Mel, Kurtis Blow, Duke Bootee and Afrika Bambaataa join the pop, rock and soul establishment with a few brief bars. Another song, “Let Me See Your I.D.” featured rappin’ promimently with performances by Melle Mel, Duke Bootee, Kurtis Blow, Scorpio, the Fat Boys and one of conscious rap’s spiritual fathers, Gil Scott-Heron.

At the end of the decade, South Africa’s apartheid regime was still in power, so American hip-hop artists held their own general assembly. Their resolution, “Ndodemnyama (Free South Africa)” was named after a protest song penned by executed African National Congress member Vuyisile Mini. ‘Beware, Mr Botha’, a choir updated the original song with the name of the country’s current president. At the time commanding respect throughout the hip-hop nation he helped found, Afrika Bambaataa reprised his role as event organizer (also producing the track together with Jazzy Jay). It makes a fair amount of sense for someone who shrouded American hip-hop in mythology with reference to the Zulu people and promoted hip-hop as an act of emancipation to speak up at the sight of South Africa’s apartheid.

Missing familiar voices of political rap (Chuck D, KRS-One, Paris), “Ndodemnyama” gathers instead a number of Afrocentric artists like X Clan, Jungle Brothers, Lakim Shabazz, Queen Latifah and even an official Nation of Islam delegate named Arthur X. Not all acts associated with it were actually involved in the recording (or can be heard in the ‘Video Version’ shown above), but the certified appearances turn this into a surprisingly diverse affair, including UTFO, Ultramagnetic MC’s and two Frenchmen – Solo, best known overseas as a founding member of French rap mainstay Assassin, and Native Tongues affiliate Revolucien.

*

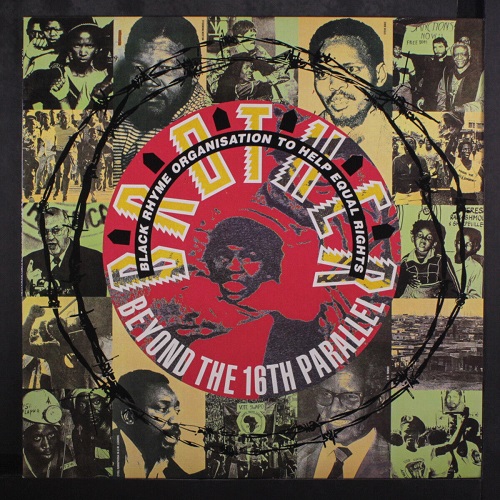

4) “Beyond the 16th Parallel” – B.R.O.T.H.E.R. (United Kingdom 1989)

Surveying the nascent scene, magazine Hip Hop Connection called it ‘British rap’s finest moment to date’ as it got in touch with Tottenham Labour MP Bernie Grant, an anti-Apartheid activist who was called upon by the rap and ragga artists who formed the Black Rhyme Organisation To Help Equal Rights (B.R.O.T.H.E.R.). Grant helped them out with explanatory remarks in which he tied the white rule in southern Africa to racial injustice in the UK.

Now you can certainly interpret the conflict the song refers to (besides Apartheid), the South African Border War, as white South Africa trying to preserve its bubble of institutionalized racial segregation. The 16th parallel thing however seems to have been an agreement that helped end the war and was part of the concessions that eventually led to the independence of South West Africa (Namibia) from South Africa.

Either way “Beyond the 16th Parallel” made for an intriguing song title. The organization included UK rap’s pioneering female group Cookie Crew and one of their pop counterparts, She Rockers, then two legendary groups who like Bernie Grant were very much in touch with their West Indian roots, London Posse and Demon Boyz, shooting star Overlord X, who was also asked to be part of American project Hip-Hop Against Apartheid, the most classic British MC of his generation, Mell’O, hardcore rap mouthpieces Kamanchi Sly and The Icepick, as well as others.

Even as it remains a footnote and doesn’t have the legacy of hip-hop’s perhaps most iconic rally for a common cause, The Stop the Violence Movement‘s “Self Destruction”, “Beyond the 16th Parallel” speaks volumes of the maturity and determination already present in UK hip-hop’s formative years.

*

5) “11’30 Contre Les Lois Racistes” – various (France 1997)

Immigrants are a typical target of racism. By the same token, calling someone an immigrant (sometimes even generations after the fact) is a very effective way of saying: You are not one of us, you can’t have what we have. While it’s debatable whether being sceptical of immigration is inherently racist, it is one of those issues where xenophobia regularly becomes part of the conversation.

Under the impression of an ecomonic downturn and the rise of the extreme-right Front National, in the mid-’80s France began to tighten its immigration laws. In the early ’90s, when the political discourse was dominated by ‘illegal immigration’ and ‘criminal foreigners’, legislation got more strict again. Citizenship wasn’t automatically granted to anyone born on French soil anymore, naturalizations of non-French spouses and family reunifications were delayed and repressions against residents with an undocumented status were enforced. At one point, legislators considered enabling police to make identity checks based on appearance – excluding color of skin…

By 1997, there was another round of legislative attempts to repress immigration at various levels. As we recall the distinction between interpersonal and institutional racism, the ‘eleven and a half minutes against the racist laws’ effectively focus on French politics, sparing neither the right nor the left, illustrating the effects of the contested laws and reminding France of its fateful colonial past. Supporting NGO Mouvement de l’Immigration et des Banlieues (MIB), nearly 20 MC’s line up to present their charges, among them Rockin’ Squat from Assassin, Akhenaton from IAM and a duo known for its uncompromising blend of street rap and political rap, Passi and Stomy Bugsy from Ministère A.M.E.R. To give at least a small sample, this crucial segment comes courtesy of Radicalkicker:

‘Anything that divides us is good for this nation

So you see, here’s what we shouldn’t do

Screw each other while the state goes through with its plans

It doesn’t like our unity, it doesn’t like our differences

Let’s all be different and united’

It has been noted that French rap, the more successful it became, learned to suppress its political compulsions. Across its entire history, however, probably no other hip-hop scene has been as explicitly political as that of France. In terms of collective projects (many others exist) “11’30 Contre Les Lois Racistes” found a timely successor in “16’13 Contre La Censure” (1999) and recently inspired “13’12 Contre Les Violences Policières” (2020), protesting decades of fatal police violence.

*

6) “Freedom (Theme From Panther) (Rap Version)” – various (USA 1995)

When Mario Van Peebles made a script by his father Melvin into a film in 1995 (to mixed reviews), ‘Panther’ generated two albums – the “Panther” OST and “Pump Ya Fist (Hip Hop Inspired By the Black Panthers)”. The soundtrack included three collective efforts. There was a male lineup for “The Points” and there were two versions of “Freedom (Theme From Panther)” – a sung version performed by a sorority of more than 75 women and a rapped version featuring some of female hip-hop’s most honorable voices. Accompagnied by dancehall queen Patra and the multitalented Me’Shell NdegéOcello, Salt-N-Pepa, MC Lyte, Queen Latifah, Yo-Yo and Nefertiti rap about equality, solidarity, spirituality, courage, independence and self-respect. And in the midst of them, TLC’s Lisa ‘Left Eye’ Lopes makes a show-stealing appearance.

It’s telling that the magnitude of the “Freedom” project (of which the ‘Rap Version’ would be the typical cheekier companion piece) has not quite been recognized.

*

7) “Adriano (Letzte Warnung)” – Brothers Keepers (Germany 2001)

On June 11th 2000 Alberto Adriano, a Mozambican man who had come to the German Democratic Republic to work as a contractor in 1988 and had founded a family, was brutally attacked by three neo-Nazis in the city of Dessau. The father of three succumbed to his injuries three days later.

It was another horrific event in a long list of xenophobic acts of aggression in re-united Germany. German hip-hop representatives had made attempts to speak up against the climate of hate since the early ’90s, among them groundbreaking crew Advanced Chemistry and the group Weep Not Child, who checked two sites of shame in the title of their 1992 EP “From Hoyerswerda to Rostock”. Both acts provided a crucial participant to German rap’s reaction to the murder of Alberto Adriano. Nigerian-German Adé Bantu (together with his brother Don Abi) from Weep Not Child intitiated the Brothers Keepers project, while Torch from Advanced Chemistry lent his credibility as a pioneer of both rapping in German and embracing an Afro-German (‘Afrodeutsch’) identity.

While the American response to the murder of Amadou Diallo at the hands of four NYPD officers, 1999’s “Hip-Hop For Respect” EP, wasn’t as impactful, “Adriano (Letzte Warnung)” reached number 5 in the German singles charts. And deservedly so. DJ Desue sets up a beat that possesses both a certain amount of mass appeal and hip-hop class while living up to the gravity and the urgency of the situation. An impressive lineup of 12 PoC MC’s, all already having earned their hip-hop stripes, heed the call with powerful, competent verses. It was a collective wake-up call in every sense, a sentiment supported by Torch’s ‘All those years we wasted airplay / You would think we rappers had nothing to say…’

“Adriano (Letzte Warnung)” is rap on its best behavior, committed and argumentative. Both a crucial moment of rap emancipation and awareness raising, this collaboration can’t be rated high enough in German hip-hop history. Ironically, part of the appeal is the militant and quite literal warning issued by the featured singer, at the time a bright young voice representing multicultural Germany, who soon came out as a Christian fundamentalist and self-professed ‘racist regardless of color of skin’ last seen doing a song with a notorious white power rock singer.

The venture extended to two albums involving an array of artists, even establishing Sisters Keepers and Brothers Keepers UK (basically one track featuring Estelle, Roots Manuva, Blak Twang and others). In 2002, the Brothers Keepers artists visited schools across the country, sometimes experiencing full-on racism on the road. If the initial purpose of the project as a sustainable social initiative was met is not known, but there is a good chance that due to its reach the message of Brothers Keepers had an influence on grassroots community work in Germany.

[See also our feature ‘Multicultural MC’ing Made in Germany’.]

*

8) “One World (We Are One)” – Taboo f/ Mag 7 (USA 2019)

Anger and/or analysis are usually the main ingredient of anti-racist messages in rap form. Songs that are essentially a celebration of unity, of differences, fit less easily into rap’s rebel image. Granted, racism requires a firm response, but rap is also the offspring of an era when music explored ways to express Black pride and to tackle discrimination and disenfranchisement from a self-assured, emancipatory angle.

It’s that attitude that informs “One World (We Are One)”, an uplifting anthem by a gathering of Native American singers and rappers. Does it mention racism or racial harmony? No. But like with many rap songs that you would still describe as an immediate reaction to racism, context is key.

(Speaking of context, listen for the Mobb Deep reference.)

The collective Mag 7 consists of Drezus (Plains Cree tribe), Supaman (Crow tribe), PJ Vegas (Shoshone/Yaqui tribes), Kahara Hodges (Navajo tribe), Doc Native (Seminole tribe), Spencer Battiest (Seminole tribe) and Emcee One (Osage/Potawatomi tribes). (Info courtesy of IllumiNative.) For “One World (We Are One)”, they’re joined by rap superstar Taboo of Black Eyed Peas, who came in contact with his Shoshone background via his grandmother and has espoused his maternal heritage in various capacities, also headlining the 2016 protest song “Stand Up/Stand N Rock”, against the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock with some of the same artists.

The concept of ‘representing’ once enjoyed considerable popularity in hip-hop music. For some artists in this field, representation is still a relevant issue. IllumiNative puts it this way:

‘We Are Still Here. Research has shown that the lack of representation of Native peoples in mainstream society creates a void that limits the understanding and knowledge that Americans have of Native communities. We are here to fight the invisibility that Natives face by amplifying contemporary, authentic Native voices, and supporting Native peoples tell their story.

We as humans all live in this one world where we have to work and live together. Our goal is for Native peoples to be normalized in a current today and show accurate and positive representations of our people.

IllumiNative is an initiative, created and led by Natives, to challenge the negative narrative that surrounds Native communities and ensure accurate and authentic portrayals of Native communities are present in pop culture and media.‘

*

9) “Time For Change” – Worldstar and Trae Tha Truth present: f/ Tamika Mallory, Trae Tha Truth, Styles P, Bun B, Mysonne, Ink, T.I., Anthony Hamilton, Conway the Machine, Krayzie Bone, E-40, David Banner, Lee Merritt (USA 2020)

The willful misinterpretation of the basic statement that ‘black lives matter’ (countered with ‘all lives matter’ or, worse, ‘white lives matter’) was simply a sneaky way of saying that black lives indeed don’t matter that much.

In an age where we are so eager to disprove each other, it’s become common to see everyone and everything being discredited. Rap fans know all about it. Sometimes we have to draw the line for ourselves when it comes to certain individuals. But it is in divisive times that the need to organize and get behind a cause becomes particularly evident. The killing of George Floyd on May 25th 2020 rekindled the #BlackLivesMatter movement as worldwide protests followed. Houston’s Trae Tha Truth found allies for what he envisioned as a ‘BLM Anthem’ and released it one month later. “Time For Change” could have found a larger audience, but streams and sales are exactly not the main measuring stick for a song like this.

*

10) “Adembenemend” – Kern Koppen, Manu, Skav, Roscovitsch, ReaZun, Rico, De Colombiaanse Bloedgroep (The Netherlands 2020)

Americans may not be aware to what degree the case of George Floyd dying at the hands of Minneapolis police rattled the world. Especially young activists took to the streets and to social media to protest police brutality and racial profiling in their communities and in solidarity with specifically Black people in the USA.

“Adembenemend”, Dutch for ‘Breathtaking’, is one such track that develops from this one tragic case to expand the picture. Even if you don’t speak Dutch (like myself), you can pick up mentions of certain far-right populist politicians, the country’s colonial history, or the figure of Zwarte Piet. Furthermore, additionally to the MC’s featured on the original track, peers were invited to publish their own versions of “Adembenemend”. The partnering organization, The Black Archives, an awareness agency that provides resources on Black history and culture in the Netherlands and abroad, stated:

‘Revolutions go hand in hand with Hip Hop. Therefore, with this initiative, we turn to the Dutch Hip Hop community and ask artists to use the instrumental we provide to record their own track against racism. The goal is to forge a chain of responses and make it resonate for as long as possible.‘

Co-initiator Manu, a spoken word artist, also made the interesting observation that ‘people who have been interested in hip-hop for many years and who care about music and culture are often people who are more substantive, and perhaps spiritual, on this topic. (…) Simply because the themes and issues surrounding racism and racist structures are topics that come to mind when you take in that catalog. Because of the affinity with hip-hop, they have given themselves more room to develop content on this theme.’

*

11) “Latinos Unidos (United Latins)” – Latin Alliance (USA 1991)

Racist Latin stereotypes are rife in US-American entertainment. Migrants from south of the border are useful bogeymen in politicians’ fearmongering.

Seeking power in numbers, groundbreaking L.A. rap artist Kid Frost parlayed his solo success at Virgin in 1990 into a collective effort for la raza. The eponymous Latin Alliance album, following just one year after “Hispanic Causing Panic”, showcased a number of up-and-coming Latin hip-hop artists. Single “Lowrider (On the Boulevard)” garnered airplay as a rap update on the WAR classic. The album itself was heavy on socio-political raps, with the posse cut “Latinos Unidos (United Latins)” marking the mission statement. Frost, going first, is followed by (not in that order) Rayski Rockswell, Markski, Lyrical Engineer, The Lyrical Latin, Hip Hop Astronaut and A.L.T. Safe for the latter (and Frost’s junior Scoop Deville, who makes himself heard in the background), research doesn’t reveal any substantial careers behind these names. Nevertheless, with Latin Alliance, Frost definitely did his part for the perennially overlooked US Latin hip-hop.

*

12) “Ikke Alene” – various (Denmark 2015)

There must be earlier examples of MC’s from the Nordic countries joining forces to denounce racism. And you couldn’t even say Scandinavians are too progressive to even have to bother about xenophobia because as of late Denmark for instance has one of the most restrictive immigration policies in Europe as migrants and asylum seekers from more distant places are often painted as a threat to the country’s welfare system and social cohesion.

Sweden’s Looptroop, who (according to one of their songs) performed their “first live show against racism in a park”, pointed to the unfolding “Fort Europa” in 2005 (as did the UK’s Asian Dub Foundation in 2002 with “Fortress Europe”), and nearly two decades later immigration hardliners continue to gain ground across Europe.

In conjunction with local NGO SOS Racisme, a collective of 7 Danish rappers (accompagnied by singer Clara Sofie) would like to let identitarians, isolationists and the like know that they are ‘not alone’, which is what “Ikke Alene” translates to. The most notable presence is Al Agami, who has been active since the early ’90s. While not possessing the same veteran status, his colleagues have done their homework. Ham Den Lange comes back to the ‘fortress’ analogy, from which he gains the perspective that ‘it’s cold at the top when the world is burning on the horizon’. Vigsø is ‘disgusted we buy fighter jets for billions / but don’t feel obligated to support refugees with war trauma’. Pede B calls out familiar scare tactics perpetuated by the media: ‘Denmark has never been more peaceful / but people think if they go to the city, they’ll get beaten up’. And Pato simply reminds immigration sceptics of the basic kindergarten lesson that ‘it’s okay to share with someone’.