Luxury rap, or as London’s Da Flyy Hooligan describes it, “gourmet rap”, is often credited as a byproduct of Roc Marciano and Westside Gunn’s influence in the 2010s, but this style of rap can be traced back further to the emergence of Rick Ross almost twenty years ago. Coming off of the bling-bling era, Ross’ brand of lavish lifestyle rap injected much-needed class and style into what was rapidly becoming a circus of garish grills and cars with rims worth more than most folk’s annual salary. By shifting the style over substance mantra to be more style is the substance we reached new levels of decadence that felt less cartoonishly overblown and more aspirational businessman. Sustainable financial success. It makes sense, considering any successful rapper ended up launching a business. Look the part, be the part, indeed.

Around this time, a counterculture ran parallel in underground Hip-Hop circles. Dead Prez, Jedi Mind Tricks, Immortal Technique and Brother Ali were leading lights, championing Islam and pushing political messaging, name-dropping authors or historical figures to embolden their claims. Humble underdogs, where honesty was king. 2007 saw the return of the Wu-Tang Clan, and in the UK, large crews helped drive home this resistance to the decadent materialism championed by the charts. We had Chain of Command, People’s Army, Poisonous Poets, Triple Darkness and Rhyme Asylum – all highly lyrical and imposing alternatives, who you would often see supporting the aforementioned US acts. Blind Alphabetz, the duo of Iron Braydz and Mohammed Yahya, was aesthetically more in line with the Rawkus 50 project, but Braydz would latterly join the super crew Triple Darkness in their expanded revision shortly after, and his style of aggressive burst-rap became more effective over imposing production.

The last ten years have seen Iron Braydz now rapping under the pseudonym Da Flyy Hooligan, shifting his content to the more prevalent luxury rap. It’s an interesting example of how Hip-Hop, specifically underground Hip-Hop, has shifted through trends over the years and come full circle. I enjoyed Hooli’s earlier material as it put a British twist on the Wu-Tang affiliate style. Sunz of Man if they grew up in London. Hooli’s approach is less rigid, but it’s jarring listening to his previous material bang on about spirituality and fighting governments, now that he’s embraced a life of capitalism. Sonnyjim experienced a similar shift in sound, scaling back the beats and drawing the focus onto his laid-back delivery – basically what Roc Marciano did, and to a lesser degree, Ransom. The influences are undeniable, and it might be because I preferred Marciano’s earlier material that had traditional beats, but I think I prefer the wild style of Iron Braydz to Da Flyy Hooligan too, as it fit his character. I can see why there was a shift though, and following a discussion around reinvention with the late, great Sean Price, it’s seemingly paid off, as Hooli is proving to be a successful UK branch of gourmet rap.

Whereas Marciano underpinned his shift away from the grit of “Marcberg” to the kingpin of “Reloaded” by crafting more intricately written rhymes, and Westside Gunn litters his albums with distractions and sound effects to the point he’s a full-blown caricature; both are effective at creating an atmosphere, or more accurately, an aesthetic. But only one has real merit as a rapper. Hooli fits somewhere in the middle, even utilising a Westside Gunn style of inflexion in his delivery on songs like “Red Belly Black Snake”. It’s admirably presented and suitably satisfying on the ear when paired with a killer DJ Babu production straight out of the Wu-Tang locker.

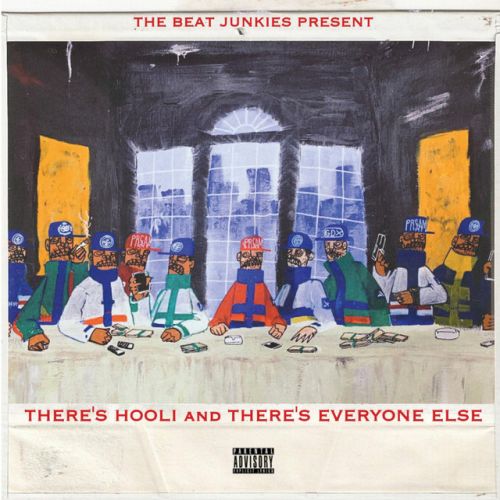

That’s right, DJ Babu of the world-famous Beat Junkies, and you’ve also got D-Styles and Rhettmatic supporting production. “There’s Hooli and There’s Everyone Else” sees Hooli rapping over traditional Hip-Hop beats, and I could hear Evidence over these instrumentals (which are helpfully included if you do wish to hear that). They are fine, for the most part, but at six songs plus an intro, it’s brief.

The track “Peace, Peace” is a reactionary piece from some criticism labelled at him from an interview, although it’s unclear where this criticism stems from outside of anonymous haters. It includes a distilled version of the interview’s content in the second verse, but it’s the flagrant use of the n-word, uncommon in emcees in England, that ultimately distracts from the messaging. Similarly, “Blood Shot” has a crazy beat from D-Styles yet the rhymes are distorted via a filter, akin to prison phone verses you used to hear on mixtapes.

Iron Braydz fans will lap up “Stoxxx N Shares”, and it’s this abusive approach to the entrepreneurial spirit that lends Hooli his appeal. He’s a hustler, with fingers in many pies, and has found success releasing through his GourmetDeluxxx label, connecting with the likes of The Purist and Griselda. “More of the Raw” includes an obvious ODB vocal, yet is anything but, as Hooli is “too good for Burberry” no doubt still considered chavvy. Tom Ford, Paul Smith, it’s all referenced here, brands that are anything but raw, but it’s also the way the rhymes are spouted at the listener in an aggressive manner that juxtaposes the nature of gourmet rap. This still possesses the Iron Braydz delivery and doesn’t really fit in with the other Hooli releases championing wining and dining. This is nastier, with threats to break your nose on a kitchen table and choke you with a telephone cable.

It’s a fascinating record, when you consider the history of Hooli, but ultimately lacks the mystique, the character, the kayfabe, something Rick Ross was brilliant at. This is my primary criticism of “There’s Hooli” – none of it seems to mean anything, or more accurately, convince. It’s a careful balancing act, retaining a grounded authenticity while indulging in expensive purchases, and it threatens to fall over. The quintessential example of this mishmash is “Gallery Oasis”, with the first verse a Phi-Life Cypher-style example of name-dropping to tell a story that doesn’t go anywhere. It starts with bands, then deviates into album names, but the second verse has no bearing at all on this. It’s a flex, just a confusing one:

“The Portishead was full of Radioheads, Bjork was bumpin’

Tricky saw his opp’ for a Massive Attack and started dumpin’

Left him lookin’ like a Limp Bizkit, fled the district

Came with an Extinction Level Event from a minor distance

Washing off his Sticky Fingaz, it was a Blur

When Papa Roach was blurting out his business, for instance

Made a deal with the Kaiser Chiefs, Stone Roses heard about it

‘Cause they never miss a beat, packin’ major heat

Beefin’ with Shaun Escoffery in the private suite

Skunk Anansie to the rescue rollin’ with a major fleet

We’re All Saints, said the Funkee Homosapien

While he kissed his teeth

But we can get Gorillaz if you n****z are really ’bout the beef

It was written in Heiroglyphics on every street

You folks are all Kurupt but you ain’t shit without the DPG

Perpetually your word is all I need, if n****z starting something

Your bitch will get a Buck 50 before we Smashing Pumpkins…”

Wu-Tang swords have been replaced by high-end fashion brands, yet it still feels little more than window-dressing. It’s very well presented, granted, yet somehow left me hollow and having grown up on that era of Triple Darkness, which includes Iron Braydz, it was difficult to enjoy this as a Hooli release, rather than a Braydz one. An odd sensation, but this Beat Junkies diversion ends up only partly succeeding. When part of a group, Hooli’s style of throwing words connects like a barrage of punches – short sharp bursts are effective – but on his own, it lacks the charm and charisma of his contemporaries. It’s why a project like “Polo Palace” with Juganaut and Sonnyjim is probably one I’d recommend over this, as the scattershot vocabulary can decorate a song more effectively in shorter stints, and having three rappers of this ilk feels suitably indulgent itself.