The thought may be hard to grasp but if we divvied up the RapReviews.com archive (that’s only, well, around 6000 reviews) into rappers playing some kind of role and rappers just being themselves, the latter would outnumber the former easily. Contrary to popular opinion, rap is the medium of the common, the regular, the average, the ordinary, the normal, the everyman. We’d have to factor quite a lot of ifs, buts and maybes into that equation, but if you know rap like we do, you can only agree. Before any spectacular image rappers try to project of themselves, their artistry is their mark of excellence. It’s what catapults them from the silent majority we all belong to at most stages of our lives into the public eye as individuals with opinions and a story.

Not each and every one of these rapping everymen and -women explicitly paints him- and herself as John and Jane Doe, but a considerable number of rap’s most highly estimated artists argue from the heart of society. In a world where the exceptional, exaggerated and extreme get the most attention, a perspective that adheres to common sense and consensus can be peculiar in itself, yet there’s also another crux of the representation of everyday routine and reality. Good rap is almost always personal, and when you really personalize something as vague as a statistic or a stereotype, things get mighty interesting.

Essa’s way of thinking and his worldview are balanced and logical, but behind them lies a major effort. This is not the kind of parrot rhyming we hear all too often from rappers who can’t think for themselves. It’s not abstract and aloof either, it’s as thought-provoking as it is honest. The way he begins opener “A View From the Middle” in a serious but still conversational tone, talking about his parents’ generation, and then slowly develops rhythm and rhyme while phrasing his artistic intent, gives you an idea of the things to come. The following “The Middle Man” fleshes out just how exactly Essa strikes his own personal balance. While rap songs typically run around in circles rhetorically, it’s evident that Essa tries to get somewhere with his arguments. In the case of “The Middle Man” that means he eventually embraces his mixed heritage as an advantage.

And so practically every song on “The Misadventures of a Middle Man” features several layers and angles. His ponderings don’t necessarily lead to conclusions, but they do in “The Invisible Man,” a song about longing for the unattainable. “Harder” covers the familiar rap trope work ethic, but the carefully detailed verse-by-verse examples betray the craftsman who’s been on the scene for well over ten years. “Sorry” initially focuses on relationships in “Sorry Seems to Be the Hardest Word” fashion, before Essa suddenly switches to another context, declaring in a very determined manner:

“What do you say

to the children of a land that was sodomized?

A land that your ancestors colonized

Do you hold up your hands and say, ‘Sorry, guys’?

Or will that not suffice?

For what word do you know that can turn wrong to right?

Fill a pot with rice, change somebody’s lot in life?

I do not decide, I merely philosophize

And if I cause offense, then I apologize…”

At times it seems like Essa has almost too much on his mind, varying choruses and changing perspectives. Or even attempting to capture silence in “Nothing to Say.” But there are songs so concentrated they hit you with full intellectual force. “Prayers of a Non Believer” is a thorough examination of heavy concepts such as faith and belief and shows that as a so-called atheist or agnostic Essa can go up against the brightest religious rappers. Despite his own stance, faith is not a joking matter to him. Neither is the topic of “Well Spoken,” even though he manages to insert humor into his observations about language and social class:

“How can it be that when I speak so clearly

ignorant people tell me the streets won’t hear me?

They want me to talk ‘blacker’

I’m like ‘What?’ – They’re like ‘More badder

You know, pure swagger?’

They say ‘If you’re a rapper, then all that matters

is not long words, it’s short skirts on tall slappers

that go like the clappers and shake their behind like maracas

You need gold like B.A. Baracus

And that’s just the way it is…’

I’m like ‘Nah, that’s what you say it is

You fools don’t even know what day it is’

They say: ‘Your audience ain’t that distinguished

The only time they’re gonna pass Maths + English

is when they hand each other Dizzee Rascal albums’

[…]

There’s a thin line between tea, dinner and supper

But it weaves between working, middle and upper

So every time an Englishman opens his mouth, he makes an enemy

But the truth is a friend to me

That’s why my mouth and my mind stay open

Till hell’s frozen – I remain well spoken”

Of course to Essa ‘well spoken’ is not synonymous with the Queen’s English or even some specific upper class accent. He simply adheres to our ideal of the articulate and rational rapper. Which is another characterization that may contradict the common perception of rap artists, but anyone having trouble believing these statements just has to take my word for it. Or Essa’s. Who’s once more fully in tune with rap history when on “Easy” he refers to his duty to ‘make it look easy’ how he keeps his work-rap balance.

Attuning his personal perspective and a universal point of view is single “The World Belongs to You.” “Man Enough” zooms in on family disputes Essa and guest rapper Doc Brown went through, while the following “Harder” begins with an acute rendition of a father-son relationship in the third person, a particularly smart way to conclude from the singular (Essa) to the plural (us).

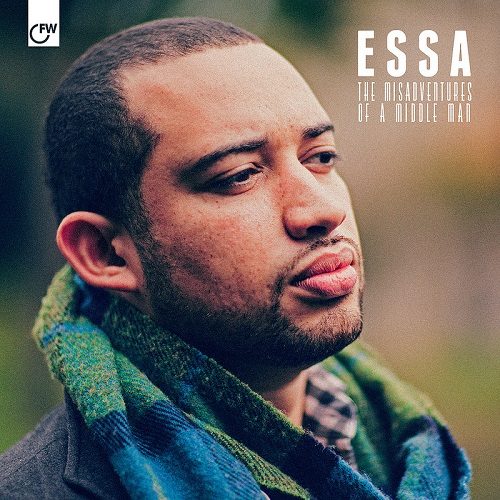

Essa’s “Misadventures of a Middle Man” will be too well (and also too soft) spoken for some. Some might also argue the inconsistent musical background that doesn’t go all the way towards soul music (as perhaps promised by the Marvin Gaye-referencing cover) and instead exerts itself with timid modern electronic touches and even a bit of gool old rap dissonance. For the most part, however, the production (including input from Wajeed, Ta-Ku, Tall Black Guy and Eric Lau) flows solidly and fully services Essa’s superb performance.

Admitted, an approach that focuses on the average man and his average life can just as well result in mediocre music, but in this case it gives us a piece of rap that is as outspoken as it is subtle. If you like an artist who is able to open your mind, Essa is up there with the best who achieve that through rhyme and reason. If his homeland decides to ignore him like it ignored so many brilliant rappers before him, he all the more deserves broader attention.