January 1st 2004 marked the bicentennial for Haiti, the world’s first black republic. Sadly, the people of Haiti had little reason to be in a festive mood. The country’s first ever democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide went into exile on February 29th after months of social and political unrest. The turmoil continued as his militant supporters revolted against the new UN-supported government, until hurricane Jeanne swept away Haiti’s remaining social stability in September.

Ever since I can remember, Haiti has been the source of only the saddest news. The bicentennial could have been an opportunity for the world to learn about its undoubtedly rich history, but instead in 2004 the focus was once again on the disheartening facts and figures. As Mike Williams reported last year for Cox News, “The World Bank lists Haiti as the fourth most undernourished nation on the planet. Haiti has the highest rate of HIV infection outside of Africa and ranks at the bottom for the availability of potable water and most other measures of development. Meanwhile, its once-lush landscape has been stripped of vegetation to make charcoal to fuel kitchen fires, leading to erosion of topsoil needed for agriculture. Finally, street crime is rampant, with drug trafficking now a major source of income for a criminal class that easily eludes a tiny national police force of less than 5,000 officers.”

It’s news like these that all too often make us forget that countries like Haiti have a healthy culture and rich tradition. Someone who has been trying to break that to us in small doses is Wyclef Jean. The son of a preacher, Wyclef was nine when his family moved from Haiti to the United States, first to Brooklyn, and then New Jersey. There, he formed a rap group with his cousin Prakazrel Michel and Michel’s classmate Lauryn Hill. In 1994, they introduced themselves to the hip-hop world as Fugees with their debut “Blunted On Reality.” While Hill herself was not of Haitian heritage, the group strived to represent Haitian immigrants, aiming to change the perception of Haitians as second-class citizens. While this original intent was slightly lost by the time the Fugees entered superstardom with their 1996 album “The Score,” the Caribbean influence remained present in their music, and when they disbanded, Wyclef started a succesful solo career as hip-hop’s multicultural maestro, continuing the Fugees fusion on albums such as “The Carnival,” “The Ecleftic”, “Masquerade” and “The Preacher’s Son.”

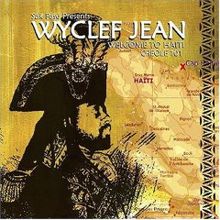

For his fifth solo offering, Wyclef Jean becomes an ambassador for Haitian and Caribbean music and culture. “Welcome to Haiti” celebrates 200 years Republic of Haiti and reflects on its joyful and painful present. This isn’t the first time Clef takes it back home, but instead of mere sprinkles of Caribbean flavor and bonus cuts found on special editions, this time you get an entire 70 minutes of collaborations with West Indian musicians, resulting in a mixture of musical styles, both traditional and contemporary. If it’s part of the West Indian music scene, it probably found its way onto this album in some form or fashion: compas/konpa, racine, twoubadou, calypso, merengue, ragga, reggaeton, zouk, etc. Hip-hop is mostly absent, safe for the few rap parts and the occasional beat reminiscent of contempo club tracks, such as the hypnotic groove of “Bay Micro’m Volume,” which could pass as a Timbaland track. It’s no surprise to learn, though, that “Welcome to Haiti” was entirely produced by long-time partners Wyclef Jean and Jerry “Te Wonder” Duplessis.

By now you should know what to expect from the Ecleftic one. Don’t be surprised to detect Arabian harmonies in “Fistibal-Festival,” or to come across a cover of Richie Valens’ classic “La Bamba” (complete with Latin guest rappers Ro-K & Gammy). The Fugees were always an inclusive concept, and Wyclef might have very well been the driving force behind that attitude, because even on a CD dedicated to Haiti, he sees the greater picture and reminisces on the African roots of the black diaspora on “Proud to Be African.” At the same time, Clef’s personal carnival stays colorblind, inviting anyone with ears to hear and body to move to join the party.

Not that many of us will understand what’s being said, as roughly 80 percent of the album’s lyrics are in creole. To grasp the meaning of songs like “24 é Tan Pou Viv” and “Lavi New York” might be crucial to understanding Wyclef Jean as an artist and as a person, but failing to understand will remind you that not every enjoyable meal comes in easy to swallow bites. Unfortunately, the album’s single, “President,” is devoid of any substantial commentary on either Bush or Aristide. One can only hope that Wyclef seizes the opportunity elsewhere, like on “Generation X,” where he seems to address the problems facing Haitian youth.

So what’s the incentive here for non-Haitians and non-Clef fans? If you can stomach his habit to massacre pop classics, if you can bare his everchanging mixture of singing/talking/rapping, if you can accept the synthetic sound that comes with the territory, if you liked “Party By the Sea” off “The Preacher’s Son” (it’s also included here), if you don’t mind an hour plus of kreyol conversation, if you wonder just what makes this guy tick, then this album is an option. Even though Wyclef is pretty predictable by now, he still remains a unique figure in hip-hop. Going back to his native country, where ‘Why-Clef’ is ‘Wee-Clef’ again, is exactly something you could only Wyclef imagine doing.

That he does it, is of no small importance to hip-hop. Because even though it’d be hard to imagine hip-hop without Jamaican transplant Kool Herc coincidentally turning into one of the founding fathers of hip-hop, the Caribbean constituency in the United States still has to fight for recognition and respect. Just think of the upset about the “Kill the Haitians” instruction in Rockstar’s Grand Theft Auto: Vice City game. In hip-hop, so far few rappers have really taken pride in their Carribean roots. Back in the days you knew rappers like Special Ed and Chubb Rock were born in Jamaica. Phife proudly called himself “Trini-born black like Mia Long’s grandmother,” Mellow Man Ace came over from Cuba with “a conga drum and some Celia Cruz records.” But for some time, the Boogie Down’s Terror Squad was the only mainstream act to refer to its Cuban, Dominican and Puerto Rican heritage. Also, Foxy Brown suddenly remembered her roots on “Broken Silence,” so it makes perfectly sense that she now appears on Wyclef’s “Haitian Mafia” to “mix the Trini mob with the Haitian squad.”

As little as you may understand of this record, what you’re gonna walk away with is the feeling that in what is often perceived as America’s backyard, there’s a sense of pride and patriotism that is just as valuable as the old “God bless America” mantra you heard so often these past months. Lest we forget, 200 years ago, that same confidence was an invaluable spark of hope in a hemisphere where slavery was still viewed as part of a God-given order.