A man who has migrated from Egypt to Europe recently made an interesting observation. He speaks the local language fairly well but not well enough for an occupation that would match his professional qualifications. The topic of our conversation was how you present yourself in a job interview. A social worker mentioned to him that like many immigrants who painstakingly have to learn a foreign language, he uses phrases that may sound correct to his ears but tend to get misinterpreted by native speakers. When for instance asked why he’s just the man for the job he applies for, he replies with “One has to be able (to perform such and such task).” The objectionable term was “One has to…,” and the social worker tried to get him to speak in a more affirming tone by saying “I can (perform such and such task, that’s why you should hire me).” This led to a discussion about cultural differences, with the Egyptian pointing out that where he is from there is one specific character who always says “I… I…” and “Me… me…” – Shaytan. Satan.

Rap is an exceptionally self-centered form of music, even for the comfortably self-centered genre of pop music. The songwriting is mostly done in the first person, and rappers can’t avoid the I pronoun for long, unquestionably the artform’s most often used subject. Even when they find a stand-in like your boy or a nigga that factors in someone outside of the I, rap is foremost a protagonist-driven medium. As such it clearly reflects our individualistic Western society where it’s often every man for himself. And yet rap is also the one form of popular music that has adopted the term representative to describe its artists, as if being a rapper makes you an ambassador or ambassadress of a particular place or people.

Anyone with a passing knowledge of this music knows that the first impression of rappers as egomaniacs usually makes way for an understanding for where a representative is coming from, not just literally, but on a social, personal and perhaps even psychological level. As B-Real once urged in one of rap’s most important moments of clarity, “How you know where I’m at when you haven’t been where I’ve been? Understand where I’m comin’ from!” Rappers take a lot of time and a lot of words to make us understand where they are coming from, and not all of them are as convincing as we wish them to be. However, there may come a time when you’ve heard the same story – be it true or false – too many times and look for rappers that occasionally leave you guessing where they’re coming from.

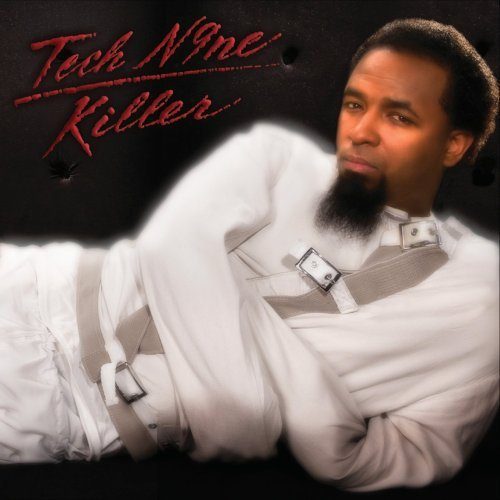

Kansas City’s Tech N9ne is one such rap artist who defies clear-cut definition. He recalls MC’s that in one way or another find or have found themselves on the periphery of the rap map. Individualists that stand out due sometimes to location, and always to style. Chamillionaire. Sir Mix-A-Lot. Twista. Krayzie Bone. C-Bo. Ludacris. Yukmouth. Eminem. Mac Dre. That’s a motley crew to be compared to, but upon close inspection Tech possesses traits of all of the above, and “Killer,” his new double disc, equips him with enough quality material to get him aligned with these often more prominent figures.

Musically and lyrically “Killer” pulls out almost all the stops. A relentless live performer, Tecca Nina makes sure to include several tracks that are bound to connect with both his cult following as well as any open-minded concert goer. On lead single “Everybody Move” his flow jumps from Luda to Twista and back, always in command of a Wyshmaster track that is highly dynamic in its own right and at the same time commanding us, “Don’t be cool, everybody move!” YoungFyre directs “Like Yeah” with stuttering snares and menacing horns as Tech channels West Coast dons C-Bo and Mix-A-Lot at their most intense. Meanwhile, “Shit Is Real” offers up escapism in the form of a rock-meets-rap-meets-reggae fusion whose hook declares: “We party cause we in pain, we party to celebrate / to keep from goin’ insane, we party just to escape.” “Crybaby,” which blasts bitching rappers, is sure to have the audience join in the lampooning with sarcastic “waaaah, waaaah”‘s.

Longtime fans might not as instantly relate to “Wheaties,” a glossy club track with an Akon-like hook and a guest verse by Shawnna. Paul Wall isn’t that surprising a feature since the two toured together, and it’s typical of Tech to let relative unknown MC The Popper star alongside the big name on “Get the Fuck Outta Here.” He also teams up with tourmates Kottonmouth Kings and Hed PE on “I Am Everything,” the latest evidence that rappers are the new rockstars, catering to a particularly persistent rock cliché with its sinister “I am everything you ever been afraid of” chorus. For those who like it a little bit more elaborate, “Paint a Dark Picture” is an impressive line of argument for an artist’s power to paint it black like the Rolling Stones in ’66, framed hauntingly by the Chamillionaire-style hook “I can write a verse and take the sun away / Say goodbye to light because it’s gone today / Ain’t no smilin’ happiness, it’s done away / Watch me paint a pic that’ll make you run away.”

Tech N9ne has never been afraid to get in touch with his dark side, but “Killer” finds him trying to move away from the black holes of obsession and depression. A flashback to “Suicide Letters” (from his “Anghellic” album), “Happy Ending” asks if it will all end on a good note for a man who claims to be numb but whose poetic sense says otherwise: “What I bled froze / so now that I’m cold-blooded and hella sick is what the med shows / The tread slows, and don’t even think you revivin’ a dead rose.” “One Good Time” is a sincere and despite the pop backdrop not sappy plea to be able to shed tears:

“I look at actors cryin’ as easy as fondue

But what do you do when extreme hurt is upon you?

Real life ain’t no movie, homie, and this ain’t John Woo

But I almost lost it an the ending of _John Q_

And I almost lost it when Jennifer Hudson blew

But I’m still waitin’ for that real emotion to come through”

The simultaneously defensive and frank “Holier than Thou” relates how Tech and his entourage in vain seeked the counseling of a gospel rapper they highly estimate. The idea seems strange stated on an album that would never fly with hardcore Christians. But it reveals a rapper who at least in theory knows right from wrong. Ultimately, however, Tech N9ne will always be on the side of the sceptics. On “Hope for a Higher Power” he understands the need for a supreme being in view of “all these tragedies” and “catastrophies,” he just has a hard time believing in it:

“If He or She is listenin’ – a mere sign can spark me

but if the laws in the Bible are bogus, then prepare for anarchy

Worst case scenario is it never ever was a higher power

So in the midst of chaos now the only real savior is firepower”

“Hope for a Higher Power” isn’t exactly up to theological speed as Tech comes across like Charlton Heston switching between Moses and NRA president, and in his role as devil’s advocate goes as far as to quote infamous cult leader Jim Jones. Still, like many other songs on “Killer,” it has its sometimes disarmingly and sometimes bizzarely honest moments. The album finds a worthy conclusion in “Last Words,” possibly the only track to incorporate a sample, a soulful, symphonic tune with a medieval touch courtesy of Michael ‘Seven’ Summers, and a great summarization of Tech N9ne the artist and Aaron D. Yates the person.

Why should anyone feel inclined to purchase a 32-track album named “Killer” by a rapper named after a firearm? Here’s why. Tech N9ne has turned into a genuinely interesting rapper. Technically, he is one of the last MC’s who exhibits flow versatility, and the dimension and the precision of it are nothing short of breathtaking. Lyrically, he covers many bases from introspection to wordplay to plain old sick shit. If he was on a Biggie or Pac level, this would be his “Life After Death” or “All Eyez on Me,” an ambitious double album that reflects the many issues on the artist’s mind and his ability to put them into song form. His music has become more accessible over the years, maybe causing the brand name Tech N9ne to lose some of its edge. About a third of the tracks are simply crazy, but the rest consists of beats that sacrifice originality for quality. Often what saves the music from mediocrity are the vocal performances, which explicitly include the spectacular Krizz Kaliko, who lends his impressive vocal range to more than a few tracks.

The main criticism regarding technicalities would be that the song sequence isn’t always stringent and that not one moment of silence separates the tracks. According to Tech, the album title is not just an excuse to (marvelously) parody the cover of the best-selling album of all time, Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” it means that the release contains all killer and no filler. Which is more wishful thinking than anything, as especially the second disc has its share of filler. The sexually explicit tracks offer up different strokes, with “The Sexorcist” being the most original song and “Drill Team” the most pointless, hardly distinguishable from “Beat You Up,” which sounds too much like a Shady Records derivative. “Pillow Talkin'” is an okay adaption of the (not-so-original) trust-no-bitch theme but features a subpar Scarface verse. With “Why You Ain’t Call Me” Tech risks being called a crybaby himself, and “Too Much” is much too short for a song that could have been disc one’s grand finale.

The filler notwithstanding, “Killer” should go down as one of the year’s key releases. Songs like “Psycho Bitch II” and “I Love You But Fuck You” are not just vintage Tech material, they show him at the height of his craft. The should-be-single “The Waitress” displays his lighter side, while “Blackboy” with veterans Brother J and Ice Cube articulately points out persistent prejudices, its host sarcastically asking, “I’m the Author of Darkness and I like the opera / so why when I’m at Macbeth they won’t treat me mo’ properer?” What do Macbeth, the opera and this Author of Darkness’ latest have in common? They all constitute art, and art is for the artist always a personal thing. That’s why rappers, who often come from a background that inspires them to take things a bit more personal, tend to talk about themselves, first and foremost. As he recounts in “Crybaby,” Tech N9ne’s Christian mother might have called rap “the evil music of today,” but rappers, while talking about themselves, taught young Aaron a language in which he could reason with himself. Rap provided him with a stage to fight his demons, and there’s nothing evil or satanic about that, it’s profoundly human.