Big Noyd is a phenomenon. He has six or seven studio albums, a best of, appeared on hip-hop classics (“The Infamous”), platinum albums (“The Professional”), successful movie soundtracks (“Blade”), underground compilations (“Lyricist Lounge 2”), shared the mic with Rakim (“Hoodlum”), been called on by fellow artists as diverse as Masta Ace and Ill Bill. And yet he doesn’t seem to have a clearly definable nor sizeable following and has not a single hit. Noyd’s curse and blessing has always been the Mobb Deep affiliation. Having made his recording debut in 1993 on the first Mobb album, he went on to guest on three tracks on “The Infamous,” and has since stuck to his violent ways, forever the stick-up kid demanding unsuspecting victims to give up the goods.

Noyd is probably the most formulaic Queensbridge rapper ever, remaining in the mix of action, rarely pausing to take a glimpse into time, being one of the anonymous hardrocks that populate the infamous Queens projects rather than a Nas-type MC who immortalizes them in his raps. As such Rapper Noyd seems to have established himself as a respected street representative, someone who does his thing on the down low but with admirable dedication. At least that’s what public opinion might amount to if anybody actually ever gave Big Noyd some thought.

Noyd made his solo debut in ’95 with the single “Recognize & Realize,” a potent track that should be part of the extended ’90s canon. While the song may have been billed to Noyd, Mobb Deep played a prominent role, Havoc as the producer and Prodigy with his guest verses. Foreshadowing the Mobb’s sinister ’96 album, “Recognize & Realize” was more “Hell on Earth” than “The Infamous,” the haunting vocal sample, punctuated piano drops, clapping drums and heavy bass creating a highly vivid atmosphere. Prodigy’s cold growl fits the beat better than his partner’s youthful swagger, but he does his best to direct all attention to his dunn, rapping, “Yo, it’s the P, me and N-o-y-d / we put the cheddar together so we could double the oz’s / and grow like some family trees and beanstalks / some hustlers, naturally born with street smarts (…) Soloists get rolled over, Rapper Noyd takin’ over.” The same is quick to refer to “the trife life,” claming that he’s “got tons of guns” and is “wearin’ handcuffs like bracelets.” As so often it’s not the entire line of argumentation that makes this track a success, but its peculiarities, the bits and pieces that make it memorable, such as the parts where he says, “My brain blunted, the lye done it / We makin’ hundreds, that’s all we wanted,” or “You didn’t hear? That nigga Noyd is extraordinaire.”

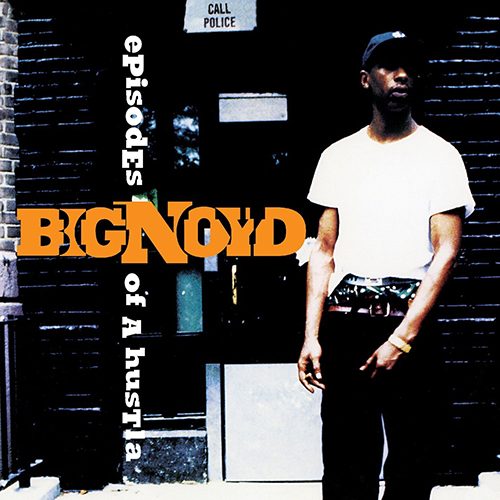

An extraordinaire rapper he was certainly not, but something about him was definitely out of the ordinary. The following album contained two skits involving cliché NYPD personel trying to get a hold of “this Noyd character,” and while storytelling ironically was virtually absent from “Episodes of a Hustla,” there was something about “this Noyd character” that made him a rapper to reckon with. He seemed to be for real, right down to the fact that he really wasn’t that much of a rapper. As he argued on “Infamous Mobb”: “Nigga please, I been in and out the joints since ’93 / so what the fuck you think you tellin’ me?”

Apart from being possibly realer than some Rapper Noyd had one thing going for him, and that was the Havoc production. In ’96 “Recognize & Realize” was followed up with “Recognize & Realize (Part 2),” just as hypnotizing as the original but a close cousin of “Hell on Earth”‘s “Nighttime Vultures.” Some of the other beats were slightly more streamlined towards average hip-hop tracks, but they still offered distinct quality production, from the mellow, uptempo “Usual Suspect” to the sparse but funky “All Pro” to the bluesy title track. Nothing, however, touched both parts of “Recognize & Realize,” to the extent that this reviewer is happy to be in possession of both in 12″ format while this short album is mainly recommended for those who don’t deal with vinyl singles.

Big Noyd’s extended career was reasonably not foreseeable, seeing how little potential he actually had. Not only had he a very unclear diction, a shaky flow and a habit of making words up, he also had nothing noteworthy to say. While his “standard for gat-handlin'” may have been “outstandin’,” the standard of his emceeing was not. The “natural born hustler” wasn’t a natural born rapper, despite his claim “The natural born hustler, lyricist Noyd finessin’ this.” It took other rappers to finesse the hustle verbally, last but not least a certain Jay-Z, who also released his first album in 1996.

Still, despite having especially Prodigy all over the album, Noyd somehow puts his stamp on each track, due to his sheer abandon. He also manages to trump expectations when he steers “I Don’t Wanna Love Again” into another than the predetermined direction. And on at least one occasion he shows unusual esprit when he rhymes:

“For those who don’t know how to act

get laid on they back

And it’s a fact:

you bust at me, I’m bustin’ back

So kid, dance to the track

Wait – analyze the rap

before you get trapped, slapped, clapped and that’s that”

Since then Big Noyd albums come and go without much fanfare, but somebody out there must be getting something out of them, and if you’re among them but not yet familiar with N-o-y-d’s beginnings, there are certainly worse rap albums to resurrect.