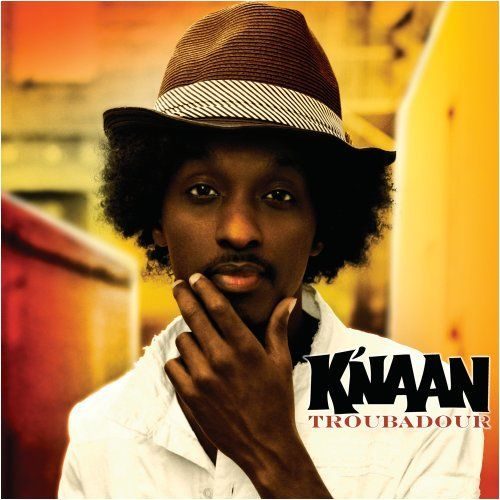

K’naan, pronounced Kay-Nahn, is a multifaceted emcee straight outta Somalia. Inspired by everyone from Fela Kuti to Bob Dylan to Nas, K’naan says he’s always been attracted to “great words and great phrases.” His album, The Dusty Foot Philosopher, has already been released in Canada, which has been his second home since moving to North America in 1991, and Australia to rave reviews and it will finally make its mark in the US on June 24th. K’naan’s story is one of triumph over extreme conditions and this week RapReviews caught up with him to find out more about his past, how he found out about Hip-Hop while living in Somalia, and what it means to be a Dusty Foot Philosopher.

Adam Bernard: In what ways did growing up in Somalia affect you musically?

K’naan: It opened my ears to so many different flavors and ideas and melodies and so on. It’s a very musical country and very much a country that’s devoted to their own sound so growing up we didn’t really get any international pop stars or anything like that, you only knew Bob Marley, everything else was domestic music. That was a big thing because you got to experience the sounds of different parts of the country. It influenced me hugely. I still write from that perspective. I still write with a certain melodic sense even when I’m rapping. A lot of rappers will follow the kick and snare, it’s how their rhythm pattern works, but because of how musically I was raised I can follow a melodic line, my rhymes can follow a guitar line or a chord. That’s how it helps me.

AB: With that Somali scene being so different, are there any aspects of it that are staples of the music, like certain sounds or instruments?

K’naan: There are a lot of different instruments that you don’t have here. Obviously, we also have the regular set, the universal set of a drum and keyboard and a guitar, those exist, but we also have other instruments. We have an instrument called Kaban, we have another one called Shareero and it’s just like even the usage of those instruments are dependant on region. It’s a very complicated musical scene. Shareero is played in the south and Kaban is played in the north. I had a healthy dosage of both because I had a very musical family which would take me to the theater and plays and all of that.

AB: When did you first hear rap music?

K’naan: Maybe I was nine or eleven or something like that. I was still back home and it was very rare that anybody would hear rap music, especially that being the humble beginnings of rap itself. The thing was my father lived in New York City and had managed to send me some music back with someone who was traveling to Somalia and that was my first dose.

AB: Wow, that was really fortuitous that he happened to be in NYC during that time.

K’naan: Yeah, he was driving a cab in Harlem and I talked to him on the phone and in fact I requested the music because I had heard it from a dude that was dating my older cousin. He played a song for me and it had a rap verse on it and I was like wow, what is that thing?! I talked to my dad and I said apparently it comes from America and it’s like talking blues and I need to hear it. He’s like, that’s called rap, that’s called Hip-Hop, and he found some.

“You have a very physical, emotional, intellectual response to this country that is so trouble ridden.”

AB: You came to North America in 1991. Have you found a way to remain close to what’s going on in Somalia now, both musically and politically?

K’naan: You can’t help but be coming form where we come from. You have a very physical, emotional, intellectual response to this country that is so trouble ridden. You constantly have to think about it, so I’m still connected. I still have a lot of family there.

AB: You call yourself The Dusty Foot Philosopher. Explain to me what that is all about.

K’naan: It’s about a couple of things. Initially when I wrote it out I was just thinking about a friend of mine who had been killed while I was still there, but soon after it became sort of like a tribute to this crew that I’m from, that I had growing up in the toughest neighborhood out of my country, my country being no tourist heaven.

AB: There are no spring break flights out there.

K’naan: Yeah (laughs). We come from what is considered by the people the toughest neighborhood in that country and I had a crew that I used to hang in. Obviously we were a part of the difficult circumstances, we were a part of the trouble, but in the evenings we would sit on top of this abandoned building, there would be like 50 of us, and we would just be talking about shit and somebody would tell a story because somebody would have a philosophical idea. We had a lot of dreamers and we’d just kind of look away from all the violence and the garbage and we’d just be talking about the essence of things and the nature of God and existence and so on. To be doing that at 11 with these kids with violent scenarios in hand, attacks right there, I thought back to them, so they were the dusty foot philosophers. We were the kids with dreams, but without means. That’s what it’s about.

“When people talk about me as a poet they’re not talking about an elite, well read, homebody kind of poet, we’re talking about street experience.”

AB: What perspectives do you think you have as a Dusty Foot Philosopher that perhaps a clean footed philosopher wouldn’t have?

K’naan: It’s a different kind of a thing. When people talk about me as a poet they’re not talking about an elite, well read, homebody kind of poet, we’re talking about street experience. When we’re talking about philosophy we’re talking about these kids who are great thinkers but they’re not afforded the opportunity to be clean footed. We’re just not from that. We’re from the poorest people on earth who are dealing with the hardest circumstances on earth. We have no privilege to us so our whole thing is not about that, our whole thing is about survival.

AB: And these are some of the topics you’re looking to go over on your album, right?

K’naan: That’s what I cover. I’ve just been thrown into this music and suddenly people have started to hear it, but honestly a lot of the songs on The Dusty Foot Philosopher were not written for other people to be enjoying. I’m glad they are, but honestly they were just written for therapeutic purposes. I would write stories of my personal circumstances and I would try to mold those hard to tell stories into songs so that the pain would transform and I’d just be able to listen to it because it had a good melody and a good beat. I did that with songs like “Smile” and a lot of different songs on the album. I didn’t think it would become an album, but they definitely helped me out.

AB: I want to talk about “What’s Hardcore?” I love how genuine your laugh is on that song. You can tell you’re really laughing at folks.

K’naan: (laughs) Yeah, cuz you’re not, though. Me and my brother used to watch TV and we’d be looking at what’s going on BET we’d just kinda look at each other like the way sheik gangsters would when they see like a really really bratty kid who got everything he wants, that’s how we looked at it. We’d just be looking at each other like wow. He’d always say “you gotta do something about this, you’re pretty good with this rap thing.”

AB: Your rhyme style is also very different from what many rap fans are used to hearing. How did you develop this flow?

K’naan: It was just something that came naturally. I think when you have your own stories and you have your own identity and you’re really honest about your own identity, because I don’t care who you are, when I meet people they meet me. Even these stars, when they meet me the thing that they immediately know is that I am who I am and I come from this country and I don’t pretend to be anyone else ever. I think that when you have that so strongly about you your whole (self) is your thing. None of my stuff has been taken from someone. I’ve developed my own way to say a phrase and it kind of gave me my own voice and therefore my own flow. I can’t tell you how it happened, but I just know that it comes from being myself.

AB: Finally, you said you wrote the album for yourself, but do you care to hazard any ideas on why it’s connecting with so many people?

K’naan: I think there are a few elements. Honestly I was surprised when I started to tour and I would see so many people at the shows singing the songs. I think what happened was because it was so genuine and so sincere to say some of these difficult things in the way that I wrote them that I think people found a universal vein within that one person’s view of the world, they just kind of connected to it. It’s also the subconscious method in my music. I would write a melody and talk about something that is not easily talked about in such a melody. Like Damien Marley said to me some time ago, we were listening back to a new song I had recorded, and he said “man, you know what’s crazy about you? You will take the most innocent and really lovable melody and you will just DOOM it with lyrics.” He said “you just doom it with harsh stories, but all the while people think they’re just listening to some sweet, catchy melody or something.” That’s been the subconscious method of my music, just because you couldn’t tell the things I tell with straight factual voice, just saying this was what happened, that would be heroin if you think about it, but if you tell it (singing) “I was stabbed by Satan on the day that I was born” then you only register it after.