Unless you have parents, friends or family members who are members of a labor union, or had an American history teacher growing up who didn’t mind showing you the darker and less glamorous side of the country’s past, it’s very possible you’ve never heard about the bloody and violent Pullman Strike that preceded the first ever recognition of Labor Day. Over 120 years later the holiday is so rote and routine we scarcely have need to think about it. Everybody looks forward to a three day weekend for the first Monday of September without having to consider more than where to go and how much suntan lotion to bring.

The workers who went on strike in 1894 weren’t thinking about an extended holiday weekend – they were thinking about how to afford to pay rent and put food on the table. Their employer, the Pullman Palace Car Company, exercised a shocking and draconian amount of control over their employees no one in modern times would find acceptable. Pullman built the “company town” where they lived on what is now the South side of Chicago. The company owned all of the employee housing, operated all of the utilities, and set their own rates for rent and services for both. This arrangement probably could have continued for years without much oversight until an economic crisis in 1893 created a national depression that caused Pullman to slash employee pay as demand for its railway cars and porters dropped across the board. Naturally they did not drop the prices they charged their employees for lodging and utilities by an equal amount, creating a literally untenable situation as Pullman workers could no longer make a living wage. A strike was the inevitable outcome.

Things came to a head on June 26th, 1894 when labor organizer Eugene V. Debs called for a boycott of Pullman cars and services, and within four days 125,000 railway workers across the nation had walked off the job in support of the boycott. If you buy into the notion of a “liberal press” you probably think this received favorable coverage given Pullman’s virtual monopoly on every aspect of their employees lives, who even before their pay was slashed were largely dependent on tips just to get by, but the reaction was largely the opposite. The workers were excoriated for bringing the nation’s railways to a halt, and at a time well before automobiles and interstates connected the U.S. from coast to coast, the nation depended on railroads for both commerce AND leisure travel. Furthermore when railroads attempted to hire new employees to replace those who walked off the job, violence erupted between “scabs” and the picketers. Many aggravated strikers also took their anger out on the lines and locomotives themselves, destroying bridges and derailing cars, which only fueled the “yellow press” to excoriate them further. There wasn’t much sympathy for labor then – not that there’s a whole lot now.

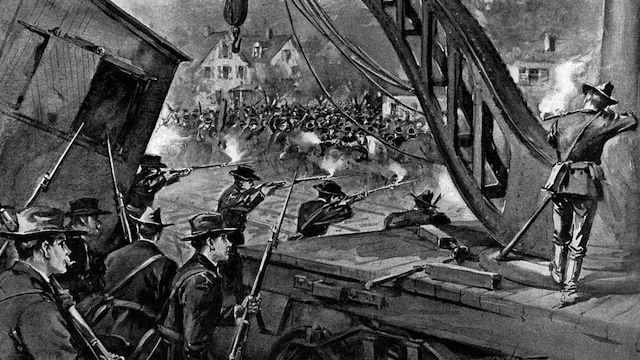

Presented with this national crisis, President Grover Cleveland and US Attorney General Richard Olney tried at every turn to make the labor unions and their striking employees unlawful. Those same workers ignored every court order and injunction and kept right on striking. The situation quickly escalated to the point federal troops were called in to break up the strike in city after city by any means necessary – and as the illustration above shows that often meant armed men firing into angry mobs at point blank range. An estimated 30 strikers died, 57 were wounded, and economic damage from the violence exceeded $80,000,000 dollars. The best adjusted for inflation amount I can calculate (most only go back to 1913) suggests this would be $160,000,000,000 today. ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY BILLION DOLLARS. To give you an idea of what that compares to the estimated economic impact of Hurricane Harvey is ONE HUNDRED AND NINETY BILLION. The strike was like a hurricane that swept across our nation, and our President’s response to this crisis was brutal and ugly. Deja vu.

Make no mistake about the racial component of this strike or the violent response to it. The whole reason Pullman workers sought to unionize was because they were disenfranchised. The Pullman Company lured in struggling post-Civil War era black men looking for an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay, but once they moved into the company town, their economic situation was little better than sharecropping in the South. There was no internet and no #BlackLivesMatter hashtag to report the indignities and the atrocities, but there was also no love lost for their suffering. Eugene Debs was public enemy number one. Democrats, Republicans, the press and the public were all against the American Railway Union and anyone who supported it. Even church ministers preached against the strike as evil. Only through the lens of history do we see the sheer magnitude of the situation and its bloody battle for what it was – the elite grinding the heel of its collective boot into the backs of the working poor with unchecked malice.

The seeds of change were sewn in blood but they nevertheless began to bear fruit. Cleveland’s administration was under pressure for both the disruption the strike caused and the violence that ensued and commissioned an investigation (too little and too late for those who died) which concluded Pullman’s town was “un-American” in its control over its workers. The Pullman Company’s monopoly on the livelihood of its employees came to an end when the Illinois Supreme Court ordered it to divest its land holdings, turning what had once been the “company town” into a more normalized Chicago neighborhood. In an effort to appease labor unions and other citizens angered by the ugly response to the strike, Cleveland and Congress pushed a bill through to make Labor Day a federal holiday just six days after the strike’s official end. As Thomas Jefferson once famously said, “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” That’s not to say violence is a solution to our nation’s problems that I want nor one that I advocate, but it is a reminder that a sleeping nation can be woken from its slumber when someone dies opposing tyranny and oppression in any form. Enjoy your holiday, but don’t forget the blood shed for it.