Hello fellow member of the information society. You will surely agree that the internet lives up to the promise of providing information at your fingertips. But you will probably also agree that we are living in a time when details in general are not deemed that important, when facts are regularly twisted at convenience, when spin doctors manipulate the media and infotainment increasingly replaces the news. People nowadays make a living out of not telling the truth. While others are just too damn lazy to find out about stuff and things. While a growing number of Americans wait for Jay Leno and David Letterman to make fun of the events they didn’t bother to follow during the day.

Still, information remains vital to the powers that be as well as to you and me. In a world where knowledge is power, it is important not to let information be monopolized by a media controlled by commercial interests, and that’s where the worldwide web faces its most noble task. Who knows, maybe blogs, message boards, and chat rooms will be instrumental in empowering the powerless around the world. As usual, however, it is up to the individual to filter all that information. What is opinion? What is fact? How to deal with the gray area that undoubtedly exists between the two? And when and how to proceed from words to action?

To break this down to our little hip-hop world, let’s say you were curious about certain artists and during a net search relied on the wrong sources. In that case let me get some facts straight. Jay-Z was never in Original Flavor (he was, however, in a group called High Potent). Korn’s “Word Up” is not a Public Enemy cover (it’s a Cameo cover). Common did not debut on Ruthless Records (that was Relativity). Cypress Hill’s debut album was not called “How I Could Just Kill a Man” (it was self-titled). Big L’s death didn’t lead to the disbanding of Children of the Corn, allowing Mase to sign with Bad Boy (Mase was a Bad Boy before Big L died). “Know the Ledge” is not by Big Daddy Kane (but by Eric B. & Rakim). Aesop Rock is not a member of the Living Legends (that’s just Aesop, no Rock). And no, in most cases Yahoo! Music is probably not ‘the best source of information about’ whoever it is you’re looking up.

Sorry for making you, the unsuspecting reader, the witness of my pedantry, but hopefully you’ll take it as an indication of the relative reliability of what you’re reading at the moment. Since I write this for a website that has made and continues to make countless statements on the subject of hip-hop, it goes without saying that people are prone to disagree with us. But if they do, we hope they disagree on opinions, not facts. Even so, RapReviews.com does contain factual errors. That’s not an assumption, it’s a certainty. Publications make mistakes all the time. It’s the ones that are reluctant to admit them that you should be weary of.

The above is my attempt to burden some of the blame as an internet representative because my pedantry doesn’t stop there as it reaches over to hip-hop writing in printed form. Take 2003’s review collection Classic Material. Its editor Oliver Wang is a respected critic who regularly drops science on politics, society, and music. Aspiring to be nothing less than The Hip-Hop Album Guide, Classic Material was the focused equivalent of our own Back to the Lab section (only that ever so often we also take pleasure in covering not-so-classic material). It’s a commendable overview of some essential rap releases, from “Rhyme Pays” to “Stankonia.” But it also contains a couple of errors, the most glaring in my eyes being the one that compelled me to write this review.

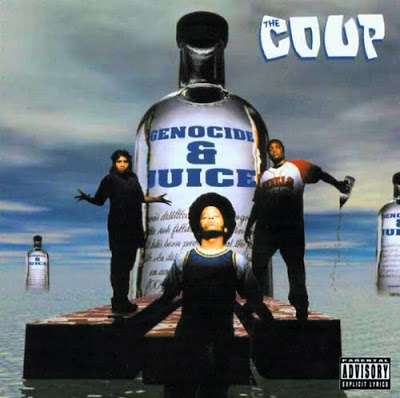

To be precise, the mistake in question is a misinterpretation. Here goes. The author of the write-up on The Coup’s 1994 album “Genocide & Juice” calls the song “Pimps (Free Stylin at the Fortune 500 Club)” ‘an attack on rap fans from high society’ when she tries to give an example for what she views as ‘overly simplistic, bumper sticker polemics.’ She goes on to single out the song “Fat Cats, Bigga Fish” as an instance where The Coup’s tracks are ‘bolstered more by the power of their personal narratives than their blanket assumptions about the rich.’ The reason I take so strongly offense to the quick condemnation and rather careless classification of “Pimps (Free Stylin at the Fortune 500 Club)” as simply ‘an attack on rap fans from high society’ is that both these songs struck me as extraordinary the first time I heard them in early 1995. More importantly, as they follow back to back and have a logical connection, I view them as invariably related like only a few rap songs in history.

It all happens over the course of one night. Rapper Boots introduces us to the character that will go from playing the lead role to that of an observer. As the sparse but cinematic background of “Fat Cats, Bigga Fish” gets in swing, he takes up his nightly hustle as a pickpocket. After coming up on “hella Andrew Jacksons,” he scrounges a burger and a drink from a female cashier and, looking for a place to eat, strolls into a parking lot filled with expensive cars, where he bumps into his cousin who just waited on a gathering of business leaders. Realizing there’s a business opportunity up there for himself, he takes his cousin’s place and enters the event as an employee. Walking amongst “snobby old ladies drinkin’ champagne with rich white men” and overhearing their conversations, he starts to realize that he’s but a small-time hustler compared to these big timers:

“One muthafucka gave me twits, and everybody else jockin’ him

throttlin’, found out later he owned Coca-Cola Bottlin’

Talkin’ to a black man, who’s he?

Confused me lookin’ hella bougie

Ass all tight and seditty

Recognized him as the mayor of my city

who treats young black men like Frank Nitti

Mr Coke said to Mr Mayor:

‘You know we got a process like Ice-T’s hair

We put up the funds for your election campaign

and oh, ehm – Waiter, can you bring the champagne?

Our real estate firm says opportunity’s arousing

to make some condos out of low-income housing

immediately; we need some media heat

to say that gangs run the street and then we bring in the police fleet

Harrass and beat everybody till they look inebriated

When we buy the land muthafuckas will appreciate it

Don’t worry ’bout the Urban League or Jesse Jackson

My man that owns Marlboro donated a fat sum’

That’s when I stepped back some

to contemplate what few know

Sat down, wrestled with my thoughts like a sumo

Ain’t no one player that could beat this lunacy

Ain’t no hustler on the street could do a whole community

This is how deep shit can get

It reads Mackaroni on my birth certificate

Poontang is my middle name but I can’t hang

I’m gettin’ hustled only knowin’ half the game”

At this point – the location remains the same – the philosophizing pickpocket clears the way for the aforementioned pimps. David Rockefeller and J. Paul Getty pass the mic in what is not so much a case of someone making fun of somebody else (unless you count Donald Trump’s unrequested appearance getting a rather cold reception from the Fortune 500), but The Coup’s clever way to drive the point that “Fat Cats, Bigga Fish” makes even further home. That the real gangsters, hustlers, and pimps are up there on the executive floors:

“If you’re blind as Helen Keller

you could see I’m David Rockefeller

So much cash, up in my bathroom is a ready-teller

I’m outrageous, I work in stages like syphillis

but no need for prophylactics

I’ma up you on to me, no match; it

ain’t puff, but my green gots amino acid

Keep my hoes in check, no rebellions if yo ass occur

Shit, it wouldn’t be the first time I done made a massacre

Nigga please, how you figure these

muthafuckas like me got stocks, bonds and securities

No impurities, straight Anglo-Saxon

when my family got they sex on

Don’t let me get my flex on

Do some gangsta shit, make the army go to war for Exxon

Long as the money flow I be makin’ dough

Welcome to my little pimp school

How you gon’ beat me at this game, I made the rules

Flash a little cash, make you think you got class

but you’re really sellin’ ass, and hoe, keep off my grass

less you’re cuttin’ it

See, I’m runnin’ shit

Trick, all y’all muthafuckas is simps

I’m just a pimp”

By dressing these symbols of capitalism up as rappers, The Coup demonstrate that America’s ruling class lives what its rappers only rhyme about. The fact that Boots and partner in rhyme E-Roc use their own rapping voice and vernacular helps to illustrate that when Rockefeller gets on the mic, there’s one major difference to your average rap star – his ass can virtually cash any check his mouth writes. If “Pimps (Free Stylin at the Fortune 500 Club)” really was ‘an attack on rap fans from high society,’ it would waste a major song on a minor problem. It’d be nothing more than a well executed sketch. It would not anticipate presidential adviser Karl Rove aping the hip-hop generation at the recent Radio and Television Correspondents Association Dinner prancing and dancing around to comedian Brad Sherwood’s rap skit that cautioned, “Listen up suckers, don’t get the jitters / but MC Rove tears the heads off of critters.” But as a biting commentary on the economical, social, and political realities, “Pimps” comes close to foreshadowing a situation where a current political puppetmaster mocks the demeanor of those that usually play no role whatsoever in his decision-making, but who nonetheless are affected by the consequences of his decisions, for instance by being sent to war.

“Fat Cats, Bigga Fish” and “Pimps” were representative of the different approach The Coup took the second time around. The group went from mentioning the communist manifesto twelve seconds into its debut, to adopting a street level perspective on its sophomore effort. While just as steeped in Bay Area rap tradition, 1993’s “Kill My Landlord” had certain academic overtones. It contained terms like “dialectical analysis” and “parasite economy,” not exactly language a rap fan would be confronted with on a Too $hort or Spice 1 record. “Genocide & Juice” still used dialectical analysis to expose a parasite economy, but it did so vividly. In Boots’ words: “Analyzed how they fucked us like if I was Dr Ruth.” The Coup stopped the finger-wagging and -pointing and began to teach by example, employing characteristics of parabels and parodies. Where they previously had written “an exposé of foul play against me and you,” they now created characters that experienced said foul play play by play.

By relying on storytelling and avoiding plain accusations, “Genocide & Juice” also reflected the immense popularity of West Coast gangsta rap, which in the early to mid-’90s enjoyed an all-time high with releases like Dr. Dre’s “The Chronic” and Snoop Doggy Dogg’s “Doggy Style” (whose “Gin & Juice” single was very intentionally referenced). Especially E-Roc, who played a much more active role compared to “Kill My Landlord,” brought a street temper to his partner’s laconic humor, a humor that also was given more exercise. Humor is a regular feature on this album, but it just as regularly provokes the kind of laughter that dies in your throat. Think of it as a social study delivered in satyrical form. Or simply Chris Rock on funk.

“Genocide & Juice” is not a cohesive narrative, although the first three songs bring it on the verge of being a concept album. “Takin’ These” kicks off right after “Pimps” is rudely interrupted by a heist. Imagine Boots and Roc changing costumes again, this time entering the party as robbers. “400 years ago… fool, where is my dough? / The year is ’94, black folks ain’t takin’ it no mo’!” E erupts. There are traces of what could be called a revolutionary agenda (name another stick-up rap song that also mentions taking over factories), and the “Molotov cocktail” is at hand in case the “Glock fail,” but apart from that the duo delivers its Robin Hood theory without ideological superstructure. “Hip 2 tha Skeme” is most effective with a sequence of social observations and corresponding commentary, such as Boots’ “When those stores get closed down?! / A system that eats itself got it lookin’ like a ghost town,” or Roc’s “I’m steady mobbin’ back to the police station / They checkin’ me, but it’s inflation that’s doin’ this takin’.”

That’s how The Coup rolled in the nine-quad – social commentary by way of reality rap: “Ain’t nothin’ happenin’ but this serious gank / while they got billions in the bank we just got money on the dank.” Their natural nonchalance was thus infused with a touch of nihilism, but The Coup focused their frustration, never letting it dissipate into a desperate fuck-the-world attitude. And while “Genocide & Juice” didn’t fail to paint a picture of hopelessness (“200’000 brothers marchin’, one mind, one place to go / ain’t no revolution, they just walkin’ to the liquor sto’ / Heard ‘Take a swigger, so it’s quicker, bro’ / The niggaroe just wants to get through the rigamarole / I been here before, a typical hoe ain’t really no different / ‘cept that she would know that can’t no prostitute become a pimp up in this system”), it wasn’t all resignation, The Coup still had some rebellion in them: “Ain’t no po’ folks gettin’ rich ‘less some caps is gettin’ peeled / ‘cept fo’ a couple muthafuckas who gon’ live the token scene / Lifestyles of the Rich & Famous, frontpage of the magazine / but that’s a known trick, tell ’em suck they own dick / I’m hip to the scheme, I’m finsta bring up the whole clique.”

“Gunsmoke,” backed by a roaring rhythm, fans the flames, as the duo further expands on why its “relationship with Uncle Sam is steamy.” The class struggle equivalent to Da Lench Mob’s racially motivated “Guerillas in tha Mist” LP, “Genocide & Juice” again and again works with imagery, lyrically recalling the inflammatory rhetoric of Ice Cube, Paris, or KRS-One. It immediately becomes less relevant when the group discusses its own struggles in the music business, but when “The Name Game” argues that their rap career just doesn’t generate enough income to “get up out the ghetto,” you’ll understand why E-Roc abandoned his career after this album because he had a family to feed. All the more he deserves praise for his solo cut “Hard Concrete,” where he looks back on a life of a young black male coming so close to his life expectancy that his demise is announced by the headlines “Young Man Shot, Cause of Death: Old Age.”

Even those who don’t subscribe to The Coup’s view of the world, or mainly use rap as a means to escape from the reality “Genocide & Juice” describes, have to acknowledge the craft that is at work here. The songwriting for both “Fat Cats, Bigga Fish” and “Pimps” is downright perfect, as the events follow a strict logic while still leaving room for creativity. An amazing amount of detail is paid to the arrangement of the lyrics and the music, and yet it all unfolds with compelling simplicity. The album continues below that particular artistic level, but follows its path with admirable consequence. More brilliant songs complete the mission – the jailhouse rap of “Santa Rita Weekend” featuring Bay greats Spice 1 and E-40, the hysterical “Repo Man,” and “Interrogation,” where all involved get their point across so intelligently it puts your neighborhood Stop Snitching campaign to shame.

In a nutshell, The Coup did like that Mac Mall line third member DJ Pam the Funkstress cuts up during “The Name Game”: “Turn up the beat and let me come with some game, mayne.” They turned up the beat by serving a juicier (no pun intended) helping of the sparse East Bay funk they had mixed the year before, this time assisted by an extended cast of musicians. And they came with some game by very vividly relating to the (rap-tested) listener that there are bigger fish to fry, resulting in a charismatic, thought-provoking, melodically rich, funky-ass album.