Like many rappers who don’t go national (or, in modern terms, viral), J. Stalin’s contemplations don’t reach the Me-against-the-world scale and scope of Tupac Shakur. When it’s always Me-against-you, naturally the potential is limited. However… it’s very telling that an artist that you deny seeing the bigger picture volunteers to bring up the issue himself: “Got my money up and seen the bigger picture”, he ventured on last year’s “Tears of Joy 2”.

As we all know, there’s a difference between claim and confirmation. Stalin himself makes that point again and again, which lands him right in the rhetorical loop where he compares competition unfavorably to himself. Of course Jovan Smith is free to apply his newfound panoramic view on things exclusively on his personal life. Still, with rap being such a heavily autobiographical genre, we do expect its representatives to go through a maturation process as artists, whether they’re on Snoop’s level or Apathy’s. Rap gives you room to grow.

Fifteen years (and twice as many releases) into his career, it appears that J Period isn’t quite fully taking advantage of that particular possibility that rap offers to its sons and daughters. What he’s mastered is gaining and maintaining a foothold in the music industry, perhaps estimably below national notoriety. He doesn’t have the irking presence of the inescapable mainstream rapper/trapper, he’s the epitome of a rap artist just doing his thing. Stalin’s thing is, not exclusively but for the most part, a contest of who hustles the hardest. When he goes about it in a combatitive way, that’s just his way to share experiences, emotions, accomplishments, realizations – in the tradition of so many Hall of Gamers and OG’s.

That’s why when I think of J. Stalin, I think of Dangerous Dame, of Richie Rich, of RBL, of 3X Krazy, of JT The Bigga Figga, of E-40 even. I also think of Too $hort, and of 2Pac. Legends in the game, who made the Bay what it is (or what it was). When I think of J. Stalin, I think of the West Coast in general, of so many promising careers that didn’t turn out to last particularly long, and for some reason I also think of DJ Quik declaring himself “America’z Most Complete Artist” back in ’92.Whether retired or still active, these people entered the history books of rap. I’d wager that by now J. Stalin is up there with them, someway, somehow. Attempting the difficult feat to write history at a time when the book seemed to be closed. He’s an old soul rap-wise, debuting under the tutelage of DJ Daryl and Richie Rich and sticking to the script the elders conceived. But he’s also part of the generation that learned to flood the market and was wise enough not to get involved with major labels. He’s an intermediary between the past and the present, exemplified by this stage-worthy wording from the 2019 song “Fraud”: “Whisperin’ Promises in the Dark like Pat Benatar / You grind for me on the block, then you my avatar”.

On “Cypress Village” the J. Stalin algorithm is at work once more, churning out songs that become interchangeable by the sheer number they are produced in. Lyrically, there’s the usual good, bad and ugly. “Nowadays you can reach me on my internet” is something a tech-savvy artist might have said in the mid-’90s and thus completely askew today (‘reach me on my internet’ yields exactly 1 Google search result). The same song, “Going Blind”, gets its title from the inane line “If you can’t see we gettin’ money, bitch, you goin’ blind”. Ever so often Stalin practices the kind of ‘songwriting’ that uses a completely random segment from a chorus as a song title. Like in the case of “In a Minute”, whose analogy “Chopper get to singin’ like he Joseph Kay” is a particularly poor appreciation of the singer’s talent. He can go lower still (from “Opp Bitch”): “I’m gon’ kill this nigga and f–k his b—h”? Come on, that’s some f—ed up s–t to say! It’s always better to leave the metaphor option open like this humorously slanted couplet does (also from “Going Blind”): “I be trippin’, family said I need a intervention / They wanna talk me out of killin’ niggas”.

So besides arguing about the arguable pen game, what is still notable about J. Stalin after all these years? First of all, he has an uncanny ability to communicate with the music he raps to, to enter into a musical conversation with the beat. Listen to “In a Minute” and “Lit Again”, the way he pauses and intonates and realize that this vocalist has a higher understanding of the connection between rap flow and instrumental. He is a little bit like Pac in that specific regard. J. Stalin can also bank on the benefit of youth because he still sounds incredibly youthful. Thus his recollections don’t seem that far away (although he never insinuates that it happened just yesterday). He may go through the motions sometimes but most of the time seems to be in touch with his emotions. A living witness of O.C.’s old adage “The more emotion I put into it, the harder I rock”, he shows himself defiant on “The Struggle”, which also (what a coincidence) makes argumentatively sense. The same goes for “I Remember”, where he condenses his astounding come-up down to a stark contrast:

“I remember I used to hide my mama crack pipe

Told her it was f–kin’ up her life

But then I start sellin’ dope

Whoa, that’s a cold f—kin’ cycle right

I lived in a crackhouse, my friends couldn’t spend the night

Mama told me long as she around I’ma be aight

She hustled hard just to buy me a Dino Bike

I hear the neighbors whisperin’ that we ain’t livin’ right

Look at me now on this first class flight

Give or take I make about 1000 a night

Came from the ghetto sellin’ hard white

Now you can sign to my label and I can change your life”

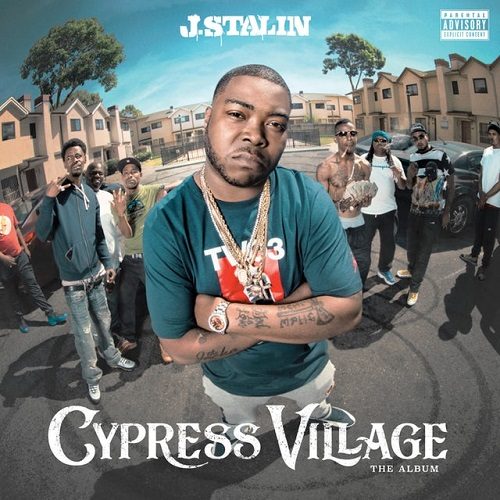

And then there’s the bond with West Oakland. The rapper knows he owes it all to the hood, that’s why every J. Stalin release so far has been “Cypress Village – The Album”, so to speak. The one that ended up with the name is a decently average entry in the artist’s body of work. Behind the boards, the notable name that emerges is White Rocks, perhaps we can also credit him (her/them) for the fitted vocal production on the opening tracks, resulting in a performance that changes between cold-blooded and urgent. We’d be remiss to not note that another one of Stalin’s essential traits is a down-to-earth demeanor, which surfaces when he describes himself as “just a little Cypress Village nigga runnin’ it up” (“Paint a Picture”) or as a “solid nigga, never flashy with a pimp cup” (“All My Chains”).

Across 23 tracks, there’s enough to choose from despite an often unisonous sound and repetitive rhetoric, from typical Bay Area weirdness (“Opp Bitch”, “Freak Like Her”, “Need My Issue”) to – White Rocks strikes again – congruent tales from the dope side like “Talkin’ Bricks” and “Stash It”. And let’s not forget the grimy title and posse track, complete with subtle beat changes courtesy of White Rocks.

Despite a number of interesting episodes and tips involving his mother (“I got the game from my mama, she taught me all that I know / Never trust a nigga, boy, never trust a hoe”) and pain and suffering (“I lost my brother to the streets, so my heart is numb / I don’t trust nobody, my best friend is a gun”), J. Stalin is no Pac. Still less is he, to come back to that unrecognized genius DJ Quik, America’s most complete artist. But like all successful rap artist (and like Pac, who was also known to repeat himself) he has struck upon a formula that winningly combines rap tradition and personal history. That still leaves room for growth – and improvement.