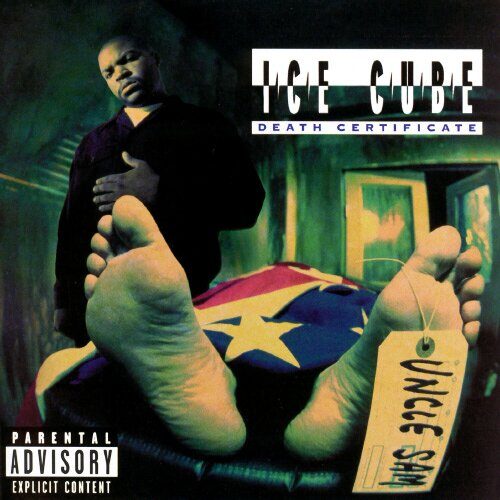

The inevitable passing of time has seriously derailed many a rap career, but it’s a particularly cruel mistress to the gangsta rapper, who must constantly be adjusting his lyrical, philosophical and public persona in order to stay relevant and fresh while not contradicting his initial nihilistic tenants. In short, he has to morph continually while remaining essentially the same (staying fresh vs. keeping it real). This is a feat too massive for many—think Spice 1, BO$$, or a number of others on Nas’ recent “Where Are They Now.” A rare few have continued to flourish after developing either a core of long-time loyalists—Too Short—or the attention of the ever-refreshed casual masses—Snoop, for example. For Ice Cube, however, time was crueler than usual, as his transition from controversial and vital voice of a generation to largely irrelevant rapper-turned-movie star was swift and total. An artist whose music, once so alive and raw, ironical popular (the one they love to hate) with both critics, rap heads, inner-city dwellers and suburban wannabes equally, has now become a rapper at turns a bland signifier of broad gangsta-isms and a satirical caricature of his former self. So looking back now at Cube’s “Death Certificate,” made at a lyrical and thematic extreme in his career when it seemed he’d never fall off, is trickier than it sounds.

Of course it’s still an visceral and satisfying listen, as the music digs deep into the funk, and the problems and solutions Cube lays out lyrically remain relevant and controversial; after all, Bush II has mostly introduced more severe versions of economic and racial maladies Bush I created. No, the hard part is listening without hindsight. We now know that after this album, which capped a string of four classic releases (starting with “Straight Outta Compton”), Cube released the funky but uneven “The Predator,” then never again reached a similar creative peak, even if he did continue to sell millions. We also know that the L.A. riots occurred shortly after the release of “Death Certificate,” for many of the same reasons and with many of the same sentiments explicitly laid out on the album. And yet it’s almost impossible to conjure up the visceral immediacy necessary to truly understand and imagine the now-ultra-rich middle-aged Cube as an angry black kid speaking for the downtrodden because he really was one of them. But yes, he once was.

A glorious mix of contradictions (as are all of rap’s most charismatic figures), Cube embodied the prototypical clever gangsta, a man both seemingly ignorant and slyly wise, with intuitive street knowledge in the tradition of 70s BaaaddAsses and the ruthless unsentimentality of 80s kingpins. With his classic hustler blueprint as a foundation and a recent passion for the teachings of the Nation driving his focus, Cube seemed equally apt to spew intellectual polemics or pistol whip a buster, a man brutal and unceasing in his philosophies, whether palatable (the demands for racial and economic justice on “A Bird in the Hand,” the critique of rap sell-outs on “True to the Game”) or not (the blanket racial indictments on “Horny Lil’ Devil” and “Black Korea,” the misogyny of “Givin’ up the Nappy Dugout”). And yet, he avoids gangsta cliché by reminding the listener that he is more of a storyteller, reporter and commentator than he is the perpetrator of the crimes and social ills he describes. “I don’t bang, I write the good rhymes,” Cube reminds us again halfway through his second LP, which signifies a further awareness of the ever-mastered skill and ever-growing responsibility of his role as rapper first and foremost, as opposed to the modern archetype of hustla/gangsta/playa using rap merely to get paid, not for love or obligation.

He was never more extreme in his unique views as he is here. It makes sense then that Cube’s lyrics and delivery dominate the album, as the dynamic and urgent sounds of “AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted” (produced by P.E.’s amazing Bomb Squad) arre replaced by in-home funk loops and simple but effective sampling. This is an album that reminds you why Bambaataa said Hip Hop was built out of Soul and Funk music, as Cube’s heavy reliance on P-Funk (in particular George Clinton’s “Atomic Dog,” which is sampled eleven times on nineteen tracks) gives the music a feeling of instant familiarity and a steady flow of energy that rarely lags.

Cube uses this heightened platform of expression to express sentiments both passionate and unfocused. While his demand for change and justice rings through clearly, it is less clear how he proposes to bring about these changes, and who is at fault. Because even though the misogyny is often apparent from the start on songs like “Givin’ up the Nappy Dugout,” these manifestos typically had deeper levels of nuance under the surface, as “Givin’ up” gains redeeming value in its more subtle messages of classism and the role of gender in Black America, for example. And even when Cube sounded seemingly non-political, as on the scathing and all-time classic dis track “No Vaseline,” he manages to convey his strong views on everything from racial and economic exploitation to the meaning of trust. So even when Cube’s intense verbal compositions became problematic in moral and intellectual ways, they still hold the technical and melodic energy to engage the listener’s undivided attention.

Looking ahead to the present from our view in the past (still with me?), when’s the last time you’ve considered a major-label artist as dangerous—not dangerous in a way threatening to individuals, but to institutions? The last time a major-label artist ridiculed and chastised so many—Asians, whites, even his own community of Blacks, not to mention no doubt angering plenty of government organizations—and didn’t have his career sabotaged by industry pressure? Cube was, then, much more than a rapper. He inhabited so many other more vital roles, from entertainer and spokesman to moral compass and educator to truth-teller and living symbol of the flawed and genius Black man. Hell, he was damn near a superhero. So crystallize this moment in space and time. LA, 1991. Now pop in that dusty version of “Death Certificate” and listen to a man who in wholly invested in his cultural, socioeconomic and ideological milieus, reminding us all why Hip Hop is important, and what power of expression it holds for those justifiably pissed off with something to say.